What does it mean to live in a ‘Predefined World’? What would be the implications of such a thing? Would a predefined life (which is to say, a life where everything has been scripted in advance) be any fun? There are a number of things we could say here. When we exist within a Predefined World then – obviously – everything we do is going to be predefined, and so is everything we think. Everything is predefined from beginning to end and nothing ever happens that hasn’t been scripted (which is of course the whole point). This means that we can’t actually be conscious in such a world, for reasons that will shortly become clear.

The first thing that we can say therefore is that there can be no such thing as ‘life in the Predefined World’; there’s no such thing as life in the Predefined World since life is essentially a spontaneous phenomenon, not something that has been coded for. Or as we could also say, life is a ‘free or genuine movement’ and no genuine movement is possible in the PD. To move from one predefined position to another is not movement – everything here exists unchangingly within the initial (and final) description of ‘how things are’. Everything is already contained in the initial state and so there’s no moving on from it. ‘Life’ (if we’re considering life to be a spontaneous kind of thing rather than ‘the acting out of a rule’) is simply not possible, therefore.

This might sound like a fairly pointless observation to be making. It’s a purely hypothetical situation anyway, we might say. It is empty conjecture (unless – that is – you happen to be someone who believes in predestination, either on religious or philosophical grounds). Predestination or predetermination is not a view that has any scientific credibility, at least not since quantum theory, chaos and complexity theory put an end to that particular worldview. We no longer labour under the strictures of the mechanical paradigm – we have taken the deterministic blinkers off in that regard.

This isn’t to say that the mechanical paradigm (or Cartesian worldview) has been devalidated (or ‘debunked’) however – it is still perfectly valid within a limited domain. The cosmos itself might be open in nature, but finite games can quite happily exist within it. Finite games (which is to say, closed systems) are a special case – ‘open’ can contain ‘closed’ but it can’t ever happen the other way around. Logic is a closed system and so therefore is rational thought (and the world it creates) and since most of us live our lives wholly within the bounds of logic, wholly within the bounds of what thought tells us is real or unreal, the limitations inherent in such an existence are very pertinent to us.

What we are essentially looking at here is the idea that life (i.e., spontaneous or unscripted life) cannot take place within the context of the rational simulation – which is to say, within the context of the world that thought has made for us. Everything that happens within a rational simulation is predefined (or predetermined) just as everything that happens in any simulation is predefined or predetermined. That’s how simulations work, obviously; that’s the only way they can work. A ‘simulation’ is the output of a set of rules and there is zero freedom in rules. Freedom can’t come about as a result of playing about with rules, no matter how sophisticated our games might be.

A life that takes place in accordance with our thoughts, in accordance with our nice, neat logical picture of the world, is not life, therefore. It’s not life because it’s not spontaneous. It’s the mechanical simulation of life, but not the thing itself. It’s perfectly true to say that when we don’t spot the simulation to be a simulation than the analogue passes itself off as the real thing; subjectively speaking it is the real thing, inasmuch as it does the same job it’s the real thing – but were we ever to look at it closely enough we would see that it isn’t, we would see that we’ve been duped, we would see that we have been the victims of a trick.

To move from one position as defined by thought to another such position is not movement – ‘the movement from one known to another is not movement’, as Krishnamurti tells us. Laughably however, we put an awful lot of effort into trying to model consciousness, into trying to put together a rational hypothesis to account for it. Just as we have said that ‘life cannot take place in the rational simulation’ (life being a spontaneous kind of affair), we can equally well say that there can be no such thing as consciousness existing within the simulation, since consciousness is also movement. If reality is ‘ungrounded (ungoverned) movement’ then consciousness must be ungoverned movement too, otherwise it’s just a sealed-off ‘private fantasy’ we’re talking about. Otherwise it’s just a wind-up toy. To imagine that consciousness has to be a function belonging to, or originating in, a closed system (which is the only thing rationality can meaningfully investigate or talk about) is remarkably obtuse of us, given that – as we have just said – a closed system can only ever be a special case – a strictly ‘provisional’ state of affairs. ‘Closed’ can only ever be a subset of ‘Open’. Why on earth would we want to go down the ‘reductionist road’ therefore? What perverse reason – we might ask – lies behind our fervent desire to ‘explain away’ consciousness by trying to put it into one or more of our unreal conceptual boxes?

To try to explain away the phenomenon of consciousness isn’t just ‘a joke’ therefore, it’s downright perverse. The branch is trying to say that the tree isn’t there and that it exists ‘all by itself’. We are denying the incomparable original (the ‘masterpiece’) in favour of a squalid copy and – what’s more – we’re patting ourselves on the back for doing so. We’re seeing our efforts as being somehow noble or heroic.

The one thing we can meaningfully say about consciousness is that it is a genuine movement as opposed to the static simulation thereof, which is ‘the linear analogue of movement’. Jung speaks of the psyche as being engaged in ‘a movement from an unknown origin to an unknown destination’, which is clearly a parallel statement. With our dull, rational way of accounting for the world, we would say that this way of talking is profoundly unscientific, yet it is the only thing we can say and saying it helps us a lot – it tells us everything we need to know. It tells us that we can’t look for consciousness (or the ‘psyche’) in a box; we don’t of course ever speak of ‘the psyche’ in modern psychology because that would imply that it was an autonomous and entity, whereas we prefer to see it as being no more than the output of a collection of dull, rule-based processes. The psyche has been downgraded into ‘the thinking mind’, which is something we can put in a box. The rational mind actually is a box – it’s a ‘box of boxes’, a collection of generic mental categories and nothing more.

Seeking to diminish (or write-off) consciousness by saying that it is ‘nothing but…’ (and you can fill in the formula however you please) is perversity but it’s a necessary perversity, from our rational point of view at least. There’s some kind of payoff in it for us, in other words – some kind of unacknowledged benefit that we’re going to obtain from doing this. When we’re looking at some sort of perverse, self-sabotaging behaviour we always look for the ‘secondary gain’ and this secondary gain always comes down to the same thing – fear. We’re looking for a type of security that just isn’t there.

We like to imagine that we are complex creatures, and that our psychology involves lots of diverse and complicated elements, but that’s just a smokescreen; our secret agenda is always to ‘shut down space’ (which is to say, to give ourselves something tangible to hang onto) and we will do whatever we have to in order to create this comforting illusion. We don’t want to see that there is such a thing as ‘genuine movement’ (or ‘ungrounded change’) no matter how interesting and enriching that might be for us. We don’t like ‘interesting’ when we’re in the state of fear – what we like is predictability, security, dependability and all that sort of thing. We like ‘boring’ – boring looks real good to us…

What we want is a nice solid hook to hang everything on. Or – to put this put this another way – what we want is a ‘fixed point of reference to relate everything to’ – that way we get to live in a world that we can always make sense of (and thus feel comfortable in). What we want, in other words, is ‘a safe and secure world, a ‘Predefined or Scripted World’…

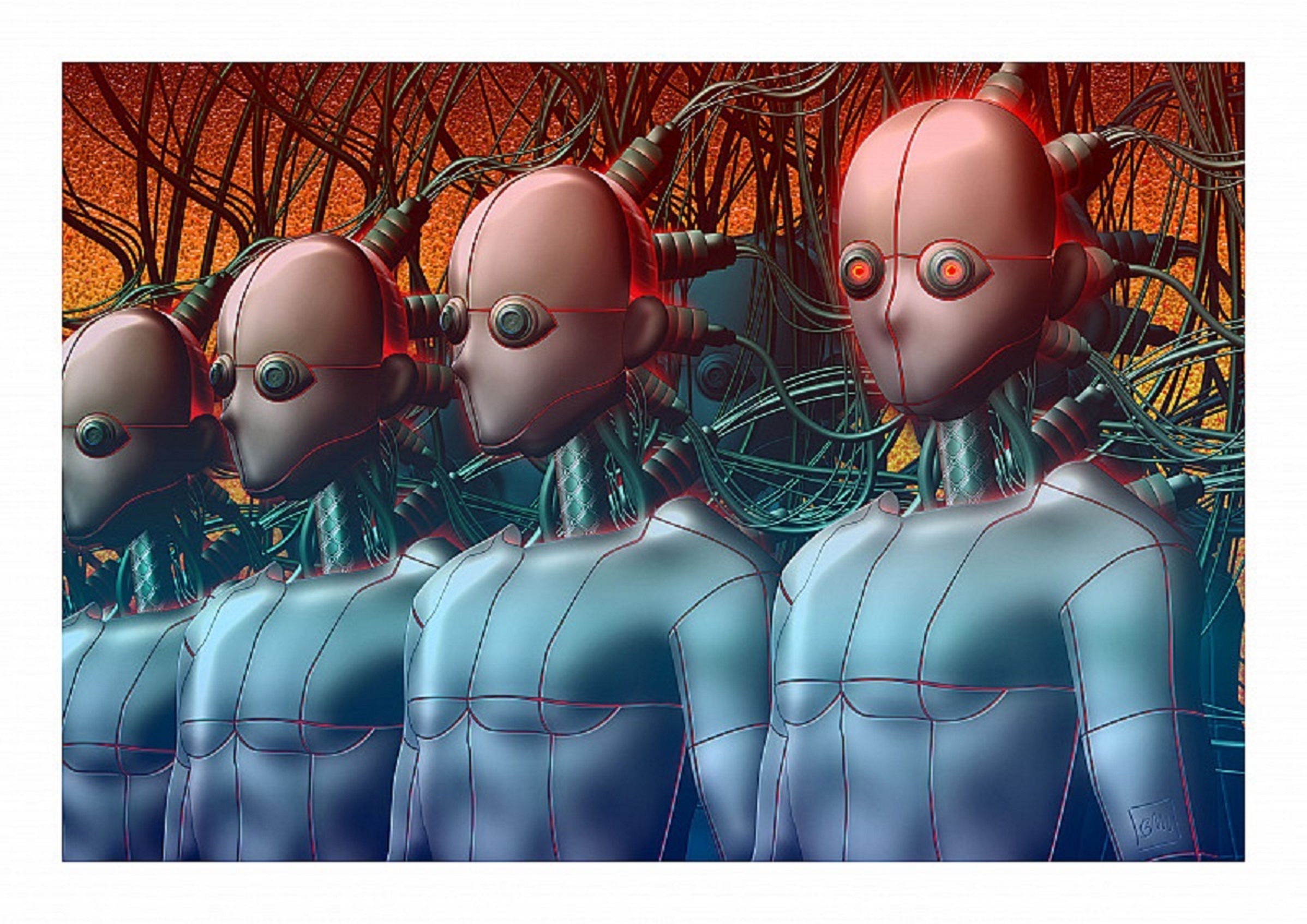

Image – Electric Barbarella, Ece Endez. On behance.net