Whenever we encounter anything, aspects of ourselves included, we always judge. Judging is what we do – we slap a label on things and then file them away somewhere in the dusty filing cabinet of the thinking mind. We judge the world and we judge ourselves and in this way we convert everything into the very unremarkable ‘World of the Known’. Everything we know is ‘all of one piece’. We think that the world which thought shows us is diverse, but it isn’t – it’s all just The World That Thought Made. To come across something that isn’t a construct of thought is to come across a foreign body, so to speak, and when we encounter a foreign body we react automatically to defend ourselves, we react defensively by immediately ‘slapping a label on it.

This is what always happens when we meet some element or other of our environment via the thinking mind – we straightaway try to make sense of it, and ‘making sense of it’ means evaluating it, judging it, conceptualising it. When do we meet something with the thinking mind we straightaway convert it into ‘the World of the Known’ and in this way make it harmless. This is how we take the threat out of it. Like a giant amoeba, thought engulfs all foreign bodies that it comes across and turns them into ‘its own thing’, which is to say, something that can be readily understand on its own terms. Thought operates by creating a simulation of the real world and so converting something into the World of the Known simply means creating a simulation of it. The Unsimulated World is a threat to the system, whereas the world that we have safely simulated IS the system.

We could equivalently say that, because of our reliance on the rational mind, we find it all but impossible to be in the world without thinking about being in the world. For the most part we don’t actually see ourselves doing it; we don’t perceive it to be the case that we’re always thinking about everything, but this is nevertheless the case because if we didn’t think about everything all of the time then the world wouldn’t be as tediously familiar to us as it is. On the contrary, it would present itself as being profoundly and eerily unfamiliar. We would be shocked if we came across the world as it is in itself, as opposed to the world that thought has made, and that doesn’t happen very often. What’s more, when it does happen (when it a bit of reality accidentally slips through our defences) we do our best to forget about it again, as Sogyal Rinpoche says.

We talk about peace and stillness in the most positive and enthusiastic way but were we to actually come across it then the experience would completely unnerve us. Stillness doesn’t support the idea that we have about who we are and to say that this lack of support is ‘uncomfortable’ for us would be to vastly understate the matter! The only thing that supports ‘the idea that we have of who we are’ is the Mind-Created Simulation of Reality and there is no stillness or peace to be found there. There might be the simulation of stillness (or a token of peace), but that’s not the same thing at all – simulations are agitations of the underlying medium and so no matter how we refine the agitation there is never going to be any stillness. Stillness is when there’s no agitation going on, peace can only arise when there is no manipulation behind the scenes. Peace cannot be made or produced in other words, it can only be uncovered.

What we’re looking for isn’t really peace but the confirmation of our underlying biases (i.e., the biases that we don’t see to be biases because they are what we use as a basis for seeing everything). When we can get the world to match how we want it to be, how we think it should be, then for us this is ‘the ideal’. This is ‘the optimum’, this is the best things could ever be. This isn’t peace however, this is contrivance, this is an artificial situation that needs to be constantly maintained and because it needs to be maintained there always has to be controlling going on, there always has to be management, there always has to be regulation. We might imagine that when everything is correctly regulated then all will be peaceful, but ‘peace’ is entirely the wrong word to use here – this is the type of ‘peace’ that comes about as a result of forcing, as a result of controlling, as a result of the repression of all unwanted possibilities, and so it is a dead or stagnant kind of peace, the kind of peace that has no freedom or joy in it. It is a dull and sterile type of stillness, as opposed to naturally occurring stillness which is vibrant and creative. Manufactured peace not peace at all; manufactured peace or stillness is not peace or stillness at all but the idea of peace, the idea of stillness.

The World That Thought Made is an equilibrium state and an equilibrium state is still only in the sense that it is devoid of any possibilities other than the one that has been specified. This can be compared to the sort of calmness that it brought about by psychological repression, the real thing being (of course) something that has to come about all by itself, without any need for forcing or controlling. With our judging we create the Equilibrium World therefore; with our labelling we create an artificial world for ourselves, a world that has no life, no vibrancy, no creativity in it. We solidify reality – which is a dynamic movement – into frozen images or concept, which we then related to in place of the living reality. We have as a result of this process of solidification or reification created a stuck situation for ourselves, a prison-like situation which we can’t escape from. This is the prison of the ego identity.

We judge the world in order to freeze it, in order to fix or solidify it, so that it will confirm or validate the idea that we have of what we think it should be and this judging happens completely automatically without us having any insight into it. We don’t know that it is happening and we don’t know that we are doing it, and there is no way that we can stop it since what we’re talking about here is a fully-automated process that can’t be turned off again once it has started. This is the process that Herbert Guenther and Chogyam Trungpa call ‘falling into error’, although this is not – as the authors are at pains to point out – a moral error but a mechanical process of ‘closing down’ that we get caught up in without realising it. In Christianity we might speak in terms of the disobedience of Eve, and the subsequent eviction and debasement of humankind, whereas the elucidation of the solidification or freezing process that Herbert Guenther and Chogyam Trungpa present us with is entirely neutral. That’s just ‘what happens in the absence of awarenesss’, and so there’s no one that we can have the satisfaction of blaming or condemning.

‘Freezing’ or ‘solidifying’ reality to make it fit our expectations isn’t a moral issue that someone needs to be punished for or warned against, but it does bring us a lot of suffering all the same. We could say that this makes it into a type of sin since suffering is clearly an evil, but this would again be an example of over-simplistic thinking. Suffering can’t be considered as an absolute evil because it is the only way we have of knowing that we have gone astray, that we have lost contact with the living reality in favour of the dull, restrictive mind-created simulation of reality. Suffering wakes us up to the full horror of our situation, and so if we say that suffering is ‘wrong’ or that suffering is ‘an evil’ then we are also saying that the perception of our true situation is wrong or an evil, which would be patently absurd. That would mean that reality itself is ‘wrong’, and needs to be struggled against.

Pain (or conscious work, which is ‘the labour of seeing the truth that we don’t want to see’) brings us back to beginner’s mind, which is the mind that knows nothing and is open to everything. According to Zen master Shunyu Suzuki,

We must have beginner’s mind, free from possessing anything, a mind that knows everything is in flowing change. Nothing exists but momentarily in its present form and color.

And elsewhere:

One thing flows into another and cannot be grasped. The true purpose is to see things as they are, to observe things as they are, and to let everything go as it goes.

When we ‘let everything go as it goes’ then we’re not judging, obviously! The whole point of judging is to ‘make things go where we want them to go’, not where they themselves were going to go. We’ve reversed the natural order of things because we can’t help thinking that we know best! We don’t know best however because when we ‘have our own way’ this inevitably brings us (despite our convictions to the contrary) to a ‘place of pain’, to a dead-end that we can’t see to be a dead-end. Obeying the thinking mind always shunts us into a dead-end. According to thoughts, according to our conditioning, ‘letting everything go wherever it is going to go’ (or ‘letting stuff be what it wants to be’) is a sure-fire recipe for disaster. We must never do this. Losing control is ‘a recipe for disaster’, we say, when actually it’s the recipe for freedom.

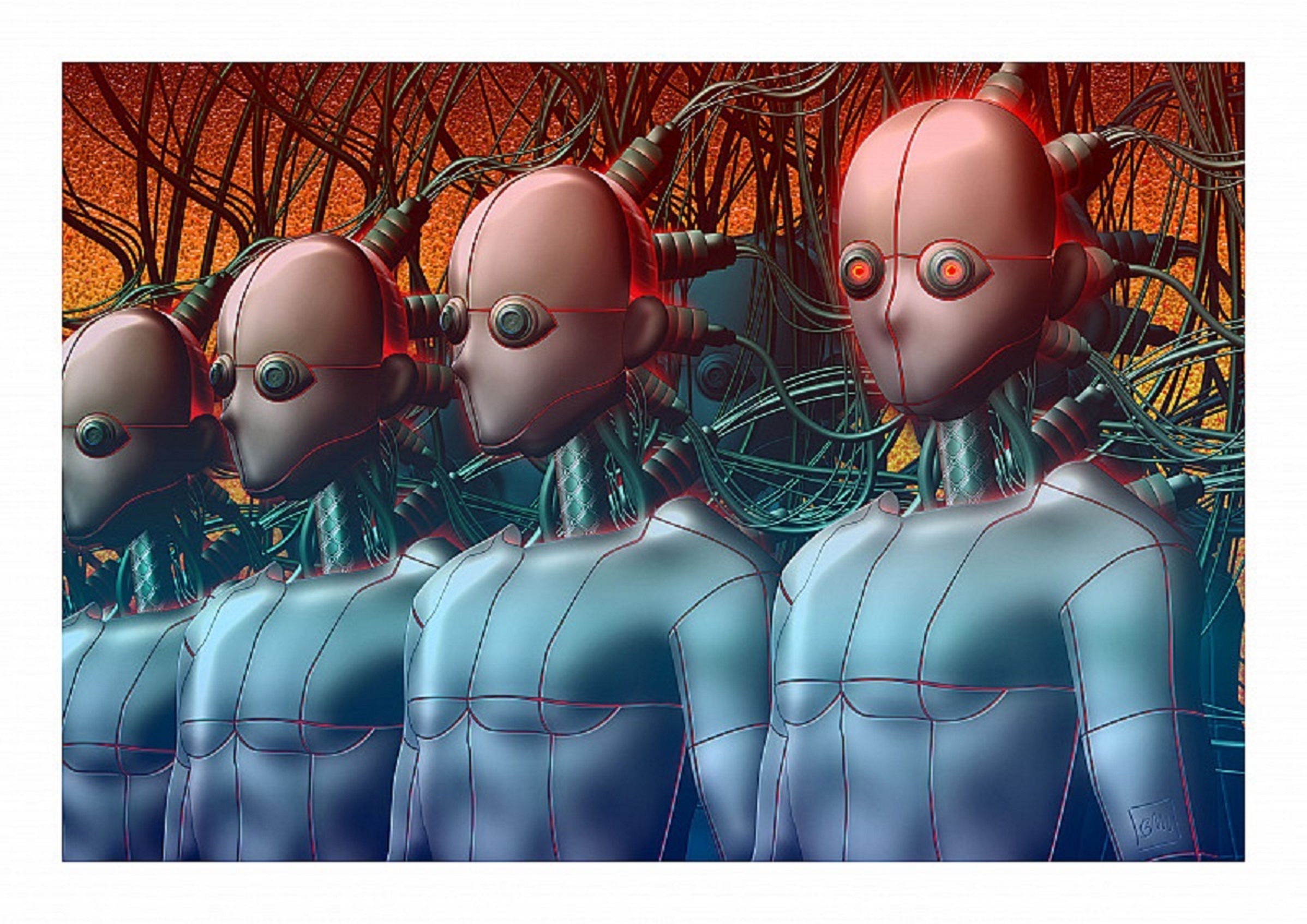

Image: wallpapersafari.com