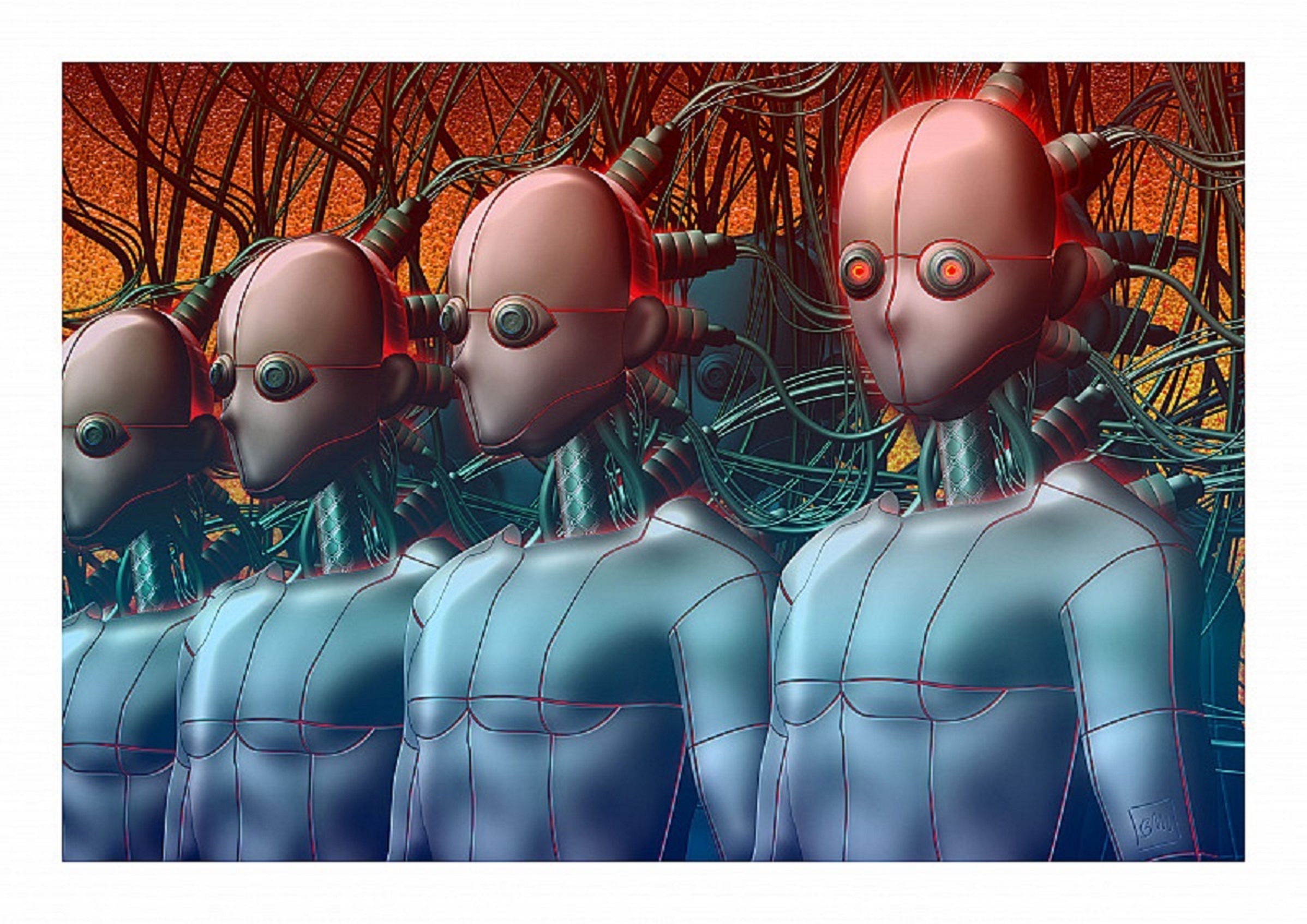

Just suppose that we weren’t ourselves at all, but that we were instead what some highly advanced kind of computer system described us as being. This very highly advanced computational system simulates us, in other words, in terms of its own logical-binary language. It simulates us in terms of a whole heap of code.

In essence – just to go into the details a little bit more deeply – what the computer does is to provide us with a precise and unambiguous specification of our identity, a specification that exhaustively defines us with regard to all possible operational parameters. Being ‘exhaustively defined’ simply means that whatever isn’t defined doesn’t get to exist. What the system doesn’t define us as being doesn’t get to exist within the terms of the simulation and therefore we are what we are defined as being and nothing else.

There is of course nothing peculiar or unusual about this – all computer programs, all digital descriptions, all mathematical models are like this. This is how all simulations work – this is how logic itself works. What doesn’t get specified doesn’t get to be there.

Having established the basis of our imaginary scenario let us now skip ahead to the next stage. Let us suppose that we are all very happy to have the high-def ‘digital identity’ that the advanced computer system has provided us with. We are feeling very proud of our new identities, just as we might feel proud of a brand new state-of-the-art, top-of-the-range smartphone that we have just purchased for ourselves. We swan around town with our new identities, checking out its capabilities, meeting up with our friends in coffee bars to compare notes and generally show off. The whole thing is a great buzz.

This initial phase of the process is all very well but the glow is quickly gone – as is always the case with ‘new things,’ no matter how fancy or how hi-tech they might be. Before we know it there is no real excitement to be had out of our fancy new digital identities and no one else wants to hear us going on about them any more either. There is no buzz to it any more and so we just ‘get on with it’. We get on with life with our new identities – we busy ourselves with getting on with whatever jobs and chores and pastimes and amusements it is that we are prone to busying ourselves with. Life goes on, with all its ups and downs…

Naturally enough, once the initial excitement wears off, these little ‘ups and downs’ become increasingly important to us. After all, we have to have something to preoccupy ourselves with – we can’t just sit there twiddling our thumbs. In the absence of anything else to interest us these ups and downs become more and more significant to us, more and more captivating, more and more engrossing. We get sucked in to the ‘mini-dramas’ of it all, we get pulled into the business of ‘maximizing the ups and minimizing the downs’.

This business – whilst engrossing enough in its own way – is at the same time wearisome enough in another way. It is wearisome because it is so humdrum, it is wearisome because it is always the same old story really and – when it comes down to it – because it is so relentlessly trivial. Because of the wearisomeness of this never-ending business of trying to maximize the ups and minimize the downs we distract ourselves on another level by dreaming of attaining the ‘ultimate UP’, the ultimate advantage of ‘not having to keep on struggling wearisomely every day to avoid the little downs and attain the little ups’. All that mini-drama stuff is just ‘swings and roundabouts’ really and on some level we know that very well, and so the dream of achieving some kind of final gain which means that we don’t have to keep on sweating the small stuff becomes very important to us in itself. This is like thinking that one day we will retire on a big pension, or thinking that one day we win the lotto jackpot and can give up our job and go and live in the South of France. It won’t happen, but thinking that it might helps us through the day.

It is of course the case that all the advantages and disadvantages are only advantages and disadvantages in relation our newly acquired digital identity. They only have meaning or relevance with regard to this assumed identity. And it is also (of course) the case that the dream of one day ‘making it big’ so that we don’t have to bother ourselves with all the crappy little stuff is also only meaningful with regard to this provisional identity – in fact the fantasy that it is possible to be an Ultimate Winner (and obtain the much-desired ‘advantage-with-no-disadvantage’) is an essential part of the conditioned identity. Without that lure we couldn’t carry on.

This wonderfully attractive fantasy scenario of ‘ultimate personal success’ is as we have said quite meaningless, quite irrelevant, outside of this extremely narrow frame of reference. It doesn’t mean a damn outside of the point of view that is the assumed identity. In fact, even saying that ‘it doesn’t mean a damn’ is making too much of it; without this very particular – and entirely arbitrary – viewpoint the whole issue of ‘sweet success versus damnable failure’ never even comes into existence.

There is a ‘basic principle’ behind what is going on here. This principle is a simple law of inverse proportionality, i.e. –

The more engrossed I get upon the job of ‘chasing after the ups and avoiding the downs’, the less aware I become of the fact the ‘ups’ and ‘downs’ in question are only meaningful from the specific point of view that I have been programmed to have.

The inverse-relationship principle which we are talking about can also be stated like this –

The more I fix my attention upon the goal of ‘obtaining the advantage’ (or ‘getting one-up in whatever situation I happen to find myself’) the less I am able to realize that this ‘advantage’, this ‘one-upmanship’, doesn’t mean a damn in the bigger scheme of things.

So if I become 100% engrossed in the attention-demanding business of ‘trying to maximize my advantages’ then I become completely unaware of the fact that the advantages in question are only ‘conditionally meaningful’ – which is to say that they are ‘only meaningful with regard to the particular conditions that I am taking for granted’. Thus, when I take my conditioned goals absolutely seriously they no longer seem conditional to me.

We could also look at this law of inverse proportionality in terms of forgetting and say that when I really throw myself into the business of chasing after all the advantages (which is to say, controlling and manipulating my situation as much as I can so as to optimize my chances of obtaining them) then in the process of doing this I completely forget that the advantages in question are quite meaningless in any real (i.e. unconditioned) sense.

When we express it like this, the principle that we are talking about does not sound very strange or unfamiliar at all, despite the tenuously hypothetical nature of our original supposition. What we are really talking about here is the basic principle behind all games, which is something that James Carse calls ‘self-veiling’. Carse’s principle of self-veiling essentially states that in order to play a game we have to voluntarily veil from ourselves the innate freedom that we have not to play the game.

Instead of saying that we are veiling or hiding from ourselves the innate and inalienable freedom that we have not to play the game we could say that what we are veiling from ourselves is our own true nature. In negative terms, we are veiling ourselves from ‘knowing that we are not the conditioned identity that we understand ourselves to be’.

Self-veiling is therefore a way of talking about ‘the freedom to play the game’, which is also what John G. Bennett is getting at when he talks about ‘negative freedom’ – the freedom not to be free.

‘Self-veiling’ (or ‘negative freedom’) creates a very peculiar situation – a situation so very peculiar that it is practically impossible to take on board. To take it on board would require a huge step out of our comfort zones, the mental equivalent perhaps of jumping from our solar system to Alpha Centauri in the one go. Since we’re generally not that keen to take even a little step out of our mental comfort zones, the chances of embarking upon a step of this magnitude are naturally very small indeed, and so it ought to come as no surprise that the peculiar situation in question is one that we are quite oblivious to.

Self-veiling creates a situation in which we are fighting against ourselves, a situation in which we are the implacable enemy of ourselves. It is inevitable that we will be ‘fighting against ourselves’ since everything we do is for the benefit of the conditioned identity, the self that has been created for us by the computer program. This is after all the only viewpoint that we are allowed to have so it goes without saying that our allegiance is to this identity. Saying that our allegiance is to the high-definition digital identity that has been provided for us by the highly advanced computer system is the same thing as saying that our allegiance is not to who we really are (which is something that we have forgotten about as a result of the operation of the principle of self-veiling) but to the digital description of ourselves. And saying that our allegiance is to the system’s description to us is of course the same thing as saying that our allegiance is to the system…

So this is pretty strange. Our fundamental allegiance is to the system which functions by denying our true nature, which functions by getting us to forget about who we really are. And yet as we have indicated the system isn’t that fantastic really – it is in fact dead boring, like some crappy satellite TV channel.

Ok, so it all seemed great at first and we were more than happy to be buying into it because it was all such a buzz, but after the initial euphoric glow died down the whole thing just got crappier and crappier, and the only way we were able to put up with it without lapsing into total despair was by pretending to ourselves that something totally impossible was going to happen! In order to keep playing the game we have to believe that something fantastic is about to happen to us, when it isn’t. The unvarnished truth of the matter is that we are left hanging on to a very limited and humdrum existence simply because it is all that we know.

And if that wasn’t bad enough there is another downside. This other downside is that by throwing in our lot with the principle of self-veiling we have unwittingly entered into a struggle with the Principle of Reality, which is obviously the deeper principle, and which will on this account always win any contest. In short, we’re fighting a losing battle. To be perfectly blunt about it, the whole thing isn’t actually real. The successes aren’t real and the failures aren’t real. The victories aren’t real and neither are the defeats. And as for the Ultimate Winning Scenario of Final Success where we don’t have to be forever struggling to ‘maintain the advantage’ – this is doubly unreal. Multiply unreal. Unreal to the power n.

All of this unreality must inevitably come to the fore one way or another, despite the fact that we are sublimely oblivious to it in the first instance. Displaced manifestations of ‘unacknowledged unreality’ (unreality we cannot see as such) inevitably appear as neurotic disturbances of one sort or another. Anxiety for example can be seen as the subliminal (or semi-supressed) awareness of the doomed nature of all our purposeful endeavours, all our attempts to ‘gain the advantage’. Depression can be seen as the barely repressed awareness of the falseness or hollowness of our assumed identity. Anxiety is dysfunctional (or displaced) fixing where what we are really trying to fix is our semi-supressed awareness of our inability to ‘do’ in any real way, since the basis of our doing is unreal. Depression is the unsuccessfully repressed awareness of our incapacity to ‘be’ in any authentic way (unsuccessfully repressed despite all the social pressure that we are under to believe in the contrary proposition). And alongside these two key positions on the ‘neurosis spectrum’ there exists all the other gradations of the various possibilities of ‘partially-repressed awareness of the truth’, along with their associated ‘characteristic dysfunctional / displaced pseudo-fixing strategies’ – which is what we see as the ‘symptomatic behaviour’ of the neurosis in question.

To put this in a more succinct fashion, we can say that in the wider scheme of things when the Principle of Reality finally starts to emerge – as it always will sooner or later – then the tattered and grimy illusion that we are grimly hanging on to will start to crumble and disintegrate in a variety of ways. When the illusory assumed identity starts at last to crumble and disintegrate this is actually very good news – the best possible news, in fact. But we won’t experience it as good news because our allegiance is all backwards – we will experience the crumbling and disintegration of the precious illusion as the worst possible news. We will experience ineffable fear and horror at the prospect of our conditioned identity’s decay and ultimate dissolution. It will be a nightmare.

Let us suppose for example that the computer system which runs the program of ‘who we think we are’ is about to be ‘switched off’. Just as long as we think that the computer-system’s description of us is ‘who we really are’ then the prospect of that description being switched off – which is bound to happen sooner or later – is bound to be utterly terrifying to us.

So if we were to know all of this from the outset, it is highly likely that we would be wondering if that initial period of ‘superficial euphoria’ is really worth all the crap that follows after it. We would be wondering if it is such a great deal after all.

This raises a question therefore – if we were to know the full story of what we were doing right from the onset – the ‘down-side’ as well as the ‘up-side’ – then would we still want to go ahead and make the radical experiment of identifying with this super-advanced computer’s simulation of us?

Art – pages.erau.edu/