Anxiety, we could say, is the result of ‘not having enough space’. It is the result of having our space taken away, eroded, encroached upon, compromised or narrowed in some way. What causes the space we have available to us to narrow (or ‘close in’) in this way is pressure – the more pressure we are under the less space we have.

The type of space we are talking about here is clearly not the space that we have around us but the space we have inside us – our ‘inner space’. But inner space and external space do share similarities and so it does make sense to compare one with the other. When our external space is taken away from us, narrowed or compromised in some way, then there is a tendency to feel claustrophobic, hemmed in, enclosed, and so on. If this process of having our external space eroded continues, the chances are that we will start to get panicky or constricted feelings. Panic comes about as a result of the feeling that we don’t have any space, the feeling that we don’t have any leeway. It comes about as a result of the very uncomfortable feeling that we are in some way up against an unyielding wall. It comes about as a result of a fundamental lack of freedom or mobility.

In the same way when our inner space is compromised we end up with the perception that we have nowhere to go, that we are ‘caught’ and this perception produces all the physical symptoms that are characteristic of anxiety: we might feel a tightness in the chest, an inability to take in a proper breath, constriction in the chest or a knot in the stomach; we might feel the need or desire to ‘break out,’ to flail wildly about in an attempt to break free, or make a run for it. All of these urges arise out of a feeling of being severely restricted or trapped. We may not look as if we are ‘trapped’ of course – but inside we are. Inside, it is as if we are up against a brick wall. Inside, it is as if we are running out of possibilities or space and as a result have to do something fast to ‘win back our freedom’, as it were. We are panicky because we feel the urgent need to get our space back.

Inner space is our ‘space to be,’ our internal freedom, and when it is encroached upon, or taken away, we feel as if we don’t have ‘the space to be’. What we have called ‘pressure’ is clearly the cause of this space-reducing process – pressure is when we aren’t allowed to be the way that we are, when we think or believe that we have to be some other way. Pressure is when we feel that ‘the way that we are’ is unacceptable, not permitted; it is when we feel that it is something to feel ashamed about, something stigmatized, something to feel bad about…

It is often hear said that a moderate amount of stress is ‘good for us’ – it is said that stress pushes us to achieve more, that it enhances our performance. But when people say this they are missing a very important point – a point that we are culturally blind to. The point is that there are two totally different types of motivation and because we do not acknowledge this we end up talking about them as if they were the same thing. We end up confusing them, merging them together. We can explain these two types of motivation quite easily by saying that one comes from within and doesn’t need to be forced, whilst the other is imposed upon us from the outside.

The first type of motivation is not about goals or rewards – it is done for its own sake, which is to say, it is spontaneous. The second type of motivation is all about escaping pressure, escaping fear, escaping pain or discomfort, escaping from guilt or shame, escaping blame, and so on. This directed type of motivation is of course much more familiar to us than the spontaneous type – sometimes it even seems to be the only type of motivation we know. The second type of motivation is all about goals and reward: our ‘reward’ in directed motivation is to ‘escape the torment’, to ‘escape the punishment’, to ‘escape the unpleasant or frightening feelings’. Our goal is to get out of the bad place we are in, to be accepted rather than unaccepted, to be approved rather than disapproved, to be allowed rather than disallowed. Our goal is to make everything OK when it is not OK.

Really – when it comes right down to it – our goal is just to ‘do whatever it is that we have to do in order to feel better’. Our goal is not ‘our’ goal at all therefore – our goal is to do whatever the guy with the big stick wants us to do and so it is his goal not ours. He will (supposedly) let us off the hook when we do what he wants and so this makes his goal our goal. This is what directed or mechanical motivation is all about – doing whatever the compulsion wants us to do, doing whatever ‘the guy with the big stick’ tells us to do. Sometimes we hear about ‘the stick and the carrot’ but the carrot is really just the relief that comes when we are no longer threatened by the stick…

Space is when we are ‘allowed’, when it is ok to be whatever or however we are. The ‘carrot’ is the hope that if we do everything we are supposed to do – if we jump through all the hoops, dot all the ‘i’s and cross all the ‘t’s if we fulfil all the criteria and meet all the standards – then at last we will be allowed, permitted, accepted, approved. The carrot is the hope that if we stringently meet all our goals, then at last we will be granted the space to be.

But this, as we know very well on a deeper level, isn’t how it works. Once we’re on the run we’re kept on the run. Once we’re on the ropes then we’re getting such a beating that we never get a chance to get back off the ropes. Once we start giving in to the pressure (once we start allowing ourselves to believe that if we successfully do whatever it is that the pressure wants us to do we will be granted peace of mind) then we are lost. Obeying pressure never leads in the long-run to the cessation of that pressure, even though it may look like it does on the short-term, any more than appeasing a bully leads to that bully being satisfied and leaving us alone. That’s not the way it works. Space can never come out of restriction – it can never come about as a result of being squeezed. No matter how hard we pressurize or squeeze ourselves we are never going to squeeze any space out of our situation.

Pressure isn’t the solution to the problem – pressure is the problem. When we are anxious as a result of being under pressure it is our natural reaction to see this anxiety a way of being that we ought not to be in. It is natural to see anxiety as a state of affairs that we should strive to ‘do something about’ and other people will of course feed into this. But if we are feeling anxious in the first place because we haven’t got enough space (because of the pressure we are under) then how can putting further pressure on ourselves, and taking away even more internal space, possibly be expected to help things?

The key to finding freedom (or ‘internal space’) is simply to notice that we are putting ourselves under pressure. As soon as we do this, as soon as we ‘catch ourselves out’ putting pressure on ourselves (in a light rather than a heavy or judgemental way) then this itself is giving us back space because noticing is giving ourselves the space to be what we are.

Noticing is ‘accepting’ whilst judging is ‘non-accepting’. When we notice ourselves reacting to a situation by putting pressure on ourselves we are not fighting against that reacting but rather we are giving ourselves the space to react. We are giving ourselves the space to be ‘the way that we are’, whichever way that is. Pema Chodron talks about noticing our own reactions with a very slight ‘inward smile’. The inner smile indicates a ‘lightness of touch’, a sense of humour about our predicament that arises naturally when we aren’t being pressurized to be one way or another. It arises as a consequence of us regaining our inner freedom or inner space, in other words. This sense of humour is our basic sanity.

It sounds strange to talk about ‘a sense of humour’ in regard to something as distressing and difficult as anxiety but the point is that when we have regained our ‘space to be’ we also regain a sense of unconditional well-being. Unconditional well-being means that we know that everything is OK even if our rational-compulsive mind is busily telling us that it isn’t OK. We are very used to automatically believing this mind (and sometimes becoming anxious as a result) but we don’t have to. It is lack of freedom that makes us believe the rational mind’s anxiety-provoking statements. It is lack of freedom that creates the ‘have to’. When there is no inner space, no inner freedom then we do ‘have to’ (i.e. we feel that we do have to do whatever the compulsion tells us to do) and when there is inner space then we don’t ‘have to’. We realize that we don’t have to. Inner space means that there are no ‘have to’s’, and this is where the ‘inner smile’ comes in.

To regain inner space is to regain the wisdom and peace of mind that comes with that spaciousness, that lack of confinement. It all comes as the one package. We regain the wisdom to see that the rational mind doesn’t have to be taken seriously, and from this insight comes peace. Insight only comes out of inner space – it never comes out of anything else. It certainly doesn’t come out of methods or goals or knowledge or book-learning. It comes out of freedom, not rules. It comes out of ‘letting go’, not ‘holding on’. It comes out of perspective.

Inner space (also known as ‘intrinsic space’) can be defined therefore as a kind of a gift. This means that it is freely given, and doesn’t have to be strained for, or struggled for. No one wins intrinsic space as a result of trying very hard, as a result of struggling. No one gains perspective as a result of straining, or as a result of beating themselves up – in fact if we do try hard, if we do strain ourselves, if we do beat ourselves up, then this very effectively blocks what we are trying to get. The rediscovery of intrinsic or inner space is the result of not putting ourselves under pressure, in other words. It occurs when we realize that it is OK to be the way that we are, whatever way that might happen to be.

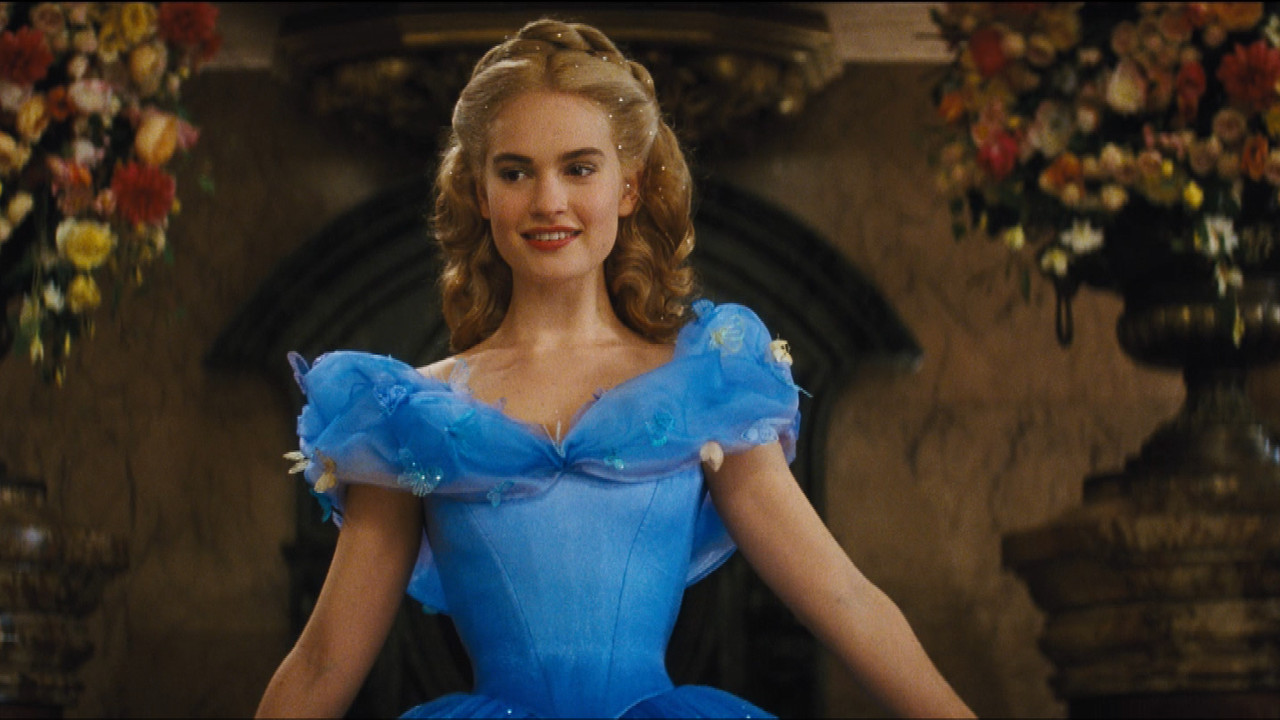

Image – fanshare.com