There are two completely different ways of looking at life (or we could also say that there are two completely different ways of living life). One way is when we see everything from the basis of thought and the other is when we see things on the basis (so to speak) of consciousness. If we can’t see that there is any way of living life other than the ‘rational’ one then this means that we are acting on the basis of thought and this is because thought cannot acknowledge anything else apart from the domain which it has itself created. Thought imposes its own game rules on the world and then refuses to give any credence to anything that does not abide by these rules. ‘If you don’t play by the rules then you don’t exist,’ says thought. Thought is the boss here therefore because thought makes all the rules.

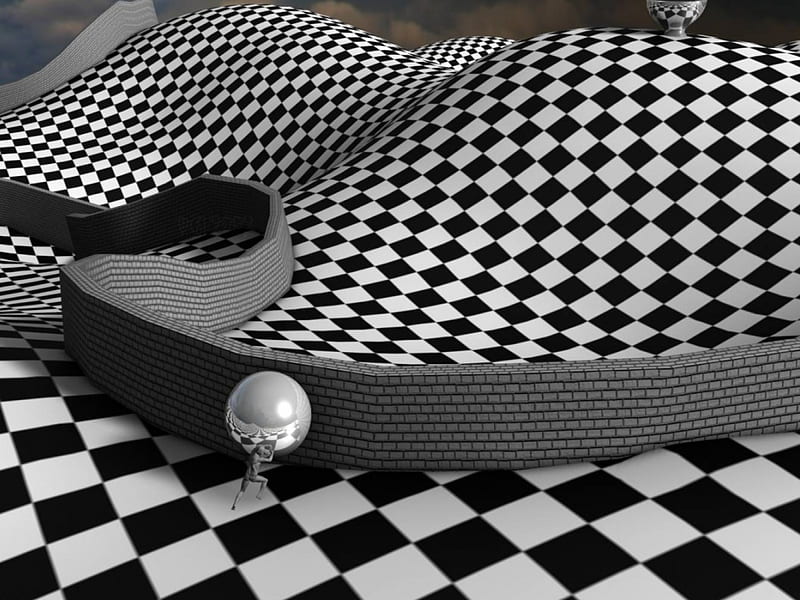

Living our lives on the basis of thought is thus a highly constrained type of business that we don’t see as such because the nature of thought is that it can’t see that it is constrained. Or to put this another way, thought doesn’t allow us to see that ‘the world which it creates for us to live in’ isn’t the real world at all, but only its version of it. (The only perspective we have is the ‘perspective’ that thought gives us, in other words). The ‘world’ thought shows us is necessarily limited because the only part of reality it shows us is the part which agrees with its rules but this limitation is not something that we can never become aware of – not so long as we are playing by thought’s rules, that is. Just as long as we believe the thinking mind when it tells us that ‘only what it tells us is true’, we naturally can’t see that the limited thought-created world is limited. This is a superlatively effective trap because there is no way out via the terms that thought itself provides us with and because there appear to be no visible inconsistencies this causes us to believe that thought is right – a rationally-orientated person will see thought as strength rather than a prison and will fight to prove that they are right at every available opportunity. They will see anyone who points out the limitations of thought as being irrational and self-deluding. They are incapable of not fighting or arguing on behalf of thought.

This is a very curious state of affairs therefore and – not only that – it is a very curious in a way that we are completely and utterly oblivious to. We cannot see that this situation which we find ourselves in is thoroughly bizarre and that the only reality we can ever know about is a reality that thought (which has nothing to do with reality) tells us of. This is like living life in the very stilted or artificial way and not being aware of it. By hypnotising us in the way that it does thought ‘makes a joke of us’ – it fools us completely and we don’t have the slightest clue that we are being suckered by it. And yet at the same time thought is functionally adaptive and so we are able to survive in this world very well by using it as a navigational aid– this is definitely a case in the short term, at any rate. Whether it turns out to be that being guided by thought is adaptive in the long run is another matter entirely however; if there is one thing we should have learned from our hundred and fifty year experiment with technology, it is that obtaining dramatic short-term benefits very much tends to come at a long-term cost. Thought is frequently very effective it comes to ‘specific discrete situations’ (because that’s all it can never see) but – ultimately – there is of course no such thing as a ‘discrete situation’, a situation that can be treated as if it isn’t connected or related to anything else. Ultimately, reality can’t be compartmentalised, and this is what causes the ‘unforeseen backlash’ that comes as a result of us intervening in a linear or logically focussed way.

This gives us a good way of explaining exactly how it is that thought is limited (or that it ‘always shows us a limited version of the world’) – thought can only ever deal an ‘isolated logical snapshot’ of what’s going on and can only ever show us a series of isolated snapshots, and yet reality itself never be reduced to a ‘series of snapshot’. This is the same as saying that reality never be ‘broken up into parts’ (or that if it is, then what we are dealing with is no longer reality). This is the Holographic Principle, which we might also call the Anaxagorean Principle, which states that there is always a bit of everything else present in any apparently ‘separate’ portion or fraction of reality (or as Anaxagoras puts it, there is a little bit of everything in everything). What the TM shows us is a world in which everything is strictly separate from everything else, a world in which an exclusion principle operates such that all the various categories of thought never mingle contents, or ‘mutually contaminate’ each other. This is Aristotle’s ‘Law of the Excluded Middle’ which says that the cat has either been put out of the house or not put out of the house, can’t be somewhere ‘in between’, or a mixture of the two’. This is the world of logic therefore, where everything is always boundaried.

It now becomes abundantly clear (from what we have just said)that the world which thought shows us is different in kind from the world which is actually real, and which isn’t any type of a ‘conceptually-mediated representation’. The world that thought shows it is ‘boundaried’, or ‘compartmentalised’, whereas the actual world isn’t. The actual world is based upon the Anaxagorean Principle rather than Aristotle’s Law of the Excluded Middle! In the actual world – as opposed to our mental representations of it – there is a little bit of everything in everything else and that is the consequence of boundaries (as Ken Wilbur says) being unreal. When we say that thought’s version of the world – which is the only version we know – is ‘limited’ then this is a grave understatement – the world that thought shows us is fundamentally sterile just as a printed menu is sterile when it comes to any nutritional value! The reason life (or reality) isn’t sterile (but is in fact endlessly creative) is precisely because there is a little bit of everything in everything. And it isn’t just a case that thought is ‘showing’ us its version of the world (which could very well be useful to us), but rather that thought’s sterile version of the world is the only world we are allowed to know about, which is most emphatically not useful.

There are no ‘parts of the whole’ when it’s reality we’re talking about, there is only the Whole, and it would serve us well to remember this. If we don’t remember this then what happens is that ‘the Whole’ becomes our enemy, something to be excluded or denied at all costs; the reason that the whole becomes our enemy is because when we celebrate the ‘unreal parts’ as being the whole (which is what we do when we exist within the Mind-Created Virtual Reality) then the genuine Whole becomes ‘that which will unfailingly negate the only world that we know or believe in’. It will also unfailingly negate us too since we are part and parcel of that world, and for both of these reasons our‘relationship’ with the-Whole-which-is-reality is going to be somewhat prejudiced, to put it mildly. It should hardly come as a big surprise to learn that we are not favourably disposed towards the Whole (even though of course we can’t let ourselves know that we aren’t since that would mean that we are actually acknowledging its existence, which is something that we can’t afford to do). Our predicament here is therefore that we are in denial of the Whole at the same time as we are put in the position of having to cherish and celebrate the unreal part, even though there is nothing ‘wholesome’ or ‘nutritious’ about it at all. We vehemently reject what is good for us and cherish what is harmful…

We are in denial of what is good and wholesome for us, and instead we are making an unholy big deal of this ‘mind-created reality’ which is, as we have said, bleakly sterile and artificial. It might be sterile and artificial but we nevertheless we keep on saying how great it is; we keep on saying how great it is even when, deep down, we get the distinct feeling that it isn’t. We don’t want to confront this feeling because the mind-created reality is all we’ve got and we are filled with existential terror at the idea of letting it go. We’re just as terrified of seeing the construct for what it is (i.e. totally devoid of all possibilities) as we are of letting go of it because seeing it for what it is with mean that we have to let go of it. It is therefore the fear of seeing the false reality for what it is that keeps us trapped in that false reality (or mine created) just as it is our fear seeing the mine created virtual identity for what it is that keeps so firmly identified with it.

As well as saying that to live life on the basis of thought is to never see beyond the veil that it draws over reality, we can also say that it is to be governed by fear in all things. We don’t know this to be true in our day-to-day lives (and we wouldn’t believe it if we were told) and that is because we (or the thinking mind) have covered up what we are afraid of and so we don’t know that it is there.To hide the thing we are afraid of and then go around saying bravely that we aren’t governed by fear is clearly a joke – the fact that we have hidden what we fear and deny its existence (so that we no longer know about it) does not in the least bit prove that we aren’t governed by fear. This ingenious argument of ours really doesn’t hold water. The thing that we have hidden away – the thing that we are in denial of – is ‘unformatted reality’ and when we are living on the basis of thoughts we are at all times taking great care that we never come in contact with it. We will say of course that we are doing other things (we will claim to be engaged in all sorts of important or meaningful projects) but what we are really engaged in is making sure that we never come in contact with unformatted reality. This is the ‘never-ending task’ that consumes all our attention.

When we are living on the basis of thought we are living a kind of ‘duplex’ existence therefore: on the one hand we are making sure that we never become aware of the world that hasn’t been formatted by thought (and this is what we are doing without ever ourselves know about it) and on the other hand we are engaging in all sorts of activities that are supposedly ‘meaningful in their own right’ but which are really only meaningful in so far as we never become aware of the fact of the fact that there is such a thing as ‘unformatted reality,’ and that we are in denial of it. When this set-up is running smoothly then – as we have said – we are ‘constrained without knowing that we are’, we are ‘limited in a completely invisible way’ and no one can tell us that we are. When the set-up isn’t running smoothly then all sorts of unpleasant awareness of start to dawn on us, albeit in a disguised or displaced sort of away, and this is what we call ‘neurotic suffering’.

In the obsessively-driven states of mind we are of course essentially trying – in a perfectly futile way – to ‘get things right’ – either for the sake of getting them right (which we might call‘euphoria-based obsession’) or because we are trying to get things right in order to ward off some sort of catastrophe (which is ‘dysphoric obsession’). In the case of anxiety – of course – we are trying to ‘get things to be right’ in exactly the same way but at the same time we know deep down that we can’t ever do this and so we are fighting against our own knowing as much as anything else. ‘Getting things to be right’ means making it seem to ourselves that the positive reality(or Mind-Created Virtual Reality) is the only reality there is (which implicitly means that there isn’t any such thing as unformatted or negative reality) and the threat of things ‘not being right’ equals the awareness (in whatever surrogate form) that there is the possibility of this thing that we have called unformatted reality. What we are anxious about therefore is the loss of security that is provided for us by the MCVR, and the MCVR can only ever function as such when we are absolutely convinced that it is the only reality there is.

The endeavour that we are secretly engaged in is the endeavour of trying to create a definite reality and the ‘enemy’ that we are fighting against is the enemy of an indefinite or uncertain one. Via the application of control, therefore, we are trying to bring about a state of certainty, even though this is inherently paradoxical since if something is certain only because we make it be then clearly it was never certain at all. Certainty is always polar in nature – that being the only way that we can create it. Any positive assertion can only ever exist in oppositional relationship to the equal and opposite negative assertion. We could say therefore that there are two (nominally different) types of certainty, the positive type and the negative type, and that we try to obtain the former (which we call ‘succeeding’) rather than the latter (which we call ‘failing’). The game we play is the game of obtaining positive certainty rather than negative and the key requirement here is that little thing we call ‘control’. When we are able to control successfully this is ‘the best possible thing’ as far as we are concerned – the good feeling we get as a result of succeeding at whatever the task is that we have set ourselves is the very best thing in the whole wide world by our reckoning. ‘Success’ is the ultimate sweet feeling and success always comes down to our ability to control.This may not sound like a particularly revolutionary statement to make but what ‘control’ actually comes down to is the ability to create a positive or certain reality, which is fantasy. There is no such thing as ‘a Positive Reality’ and there never could be.

‘Neurotic suffering’ – we might say – is the suffering that comes about when we either have to work too hard at creating the Positive Reality or when the Positive Reality we have created becomes so denying of us that the pain it causes us isn’t worth the benefit (i.e. the sense of ontological security) that it provides us with. When we are working too hard to maintain the +R then this activity itself becomes a source of pain and exhaustion for us. This is a ‘double-whammy’ because not only is there the distress and exhaustion that is being generated by our over-clocked mental activity, the fact that we are having to try so very hard inescapably draws our attention to the fact that [1] There is a problem and [2] That we might not be able to fix it. If we aren’t able to fix the problem despite all our efforts (which is invariably the case in all neurotic conflict) then this causes us to become aware of the possibility of an impending calamity which – if it happens – is going to be so terrible that we don’t have any way of understanding how terrible it will be. All we know is that it is going to be ‘a bad thing’, and not just a bad thing (of course) but the mother of all bad things.The other possibility that we mentioned is the scenario where we are able to maintain +R but the +R is so denying of us that to actually live in it is no longer a tenable proposition. There is nothing even remotely enjoyable in our existence, in other words, and so although we still have this sense of ontological security, there is absolutely no joy at all in it.

All mind-created realities are denying of us –necessarily so since they are by their very nature sterile – but most of the time there is a false sense of perspective, a false sense of spaciousness that makes us feel as if we have genuine possibilities open to us. In the closed world that is created by thought there can be no other possibilities that are open to us – since the mind-created ‘reality’ is only what it is defined as being – and so any appearance that there are ‘possibilities that are open to us’ are just that – appearances. Instead of saying that the mind-created +R is denying of us and that it causes suffering on this account, we could equally well say that it is ‘too small for comfort’, just as a small enclosure for lions or elephants or polar bears in a zoo are generally too small for comfort (or, rather, ‘too small to support well-being’). Just as large animals in a zoo can sometimes be visibly seen to be suffering from mental ill-health as a result of their imprisonment, we too can suffer from the ‘impoverishment of the world’ that the thinking mind has created for us to live in. We might like to think that depression is caused by faults in our DNA, or in our brain chemistry, or in our cognitive processes, but such ‘explanations’ are just red herrings, ways of conveniently distracting ourselves from what’s really going on, which is that we have (no matter how unwittingly) opted to live in the very small world that thought has created for us.