We live a conceptually-mediated world without knowing that we do. Or to put this another way, we live in a world that is made up of our thoughts whilst imagining the whole time that it is the real world, (which is to say, a world that we ourselves haven’t made up). No sort of therapeutic change worthy of the name can ever take place, very clearly, unless we first see this. We have to leave all of our thinking behind, not just some of it. This might seem to some like a rather blunt and uncompromising statement to come out with but – when we reflect on the matter it becomes self-explanatory – obviously there can be no meaningful change or growth unless we gain some perspective on our lives. Perspective can only come when we have moved away, to whatever extent, from that position where we unreflectively accept a thought-created or conceptually-mediated world as being synonymous to (or identical to) the real thing.

Psychological growth comes about as a result of the separation of ‘what is truly us’ from ‘what we mistakenly thought to be us,’ in other words. No separation of the one from the other means no growth! Growth is quintessentially intrinsic in nature and has therefore nothing to do with ‘adaptation to an external environment’. The alternative to growth is where we conform ever closer to a framework that has been arbitrarily imposed upon us by our culture. In the first case something ‘bursts out from within us,’ whether we like it or not, whilst in the second case we adapt ourselves to the prevailing standards in what is an entirely ‘unconscious’ process, which is to say, a process that involves absolutely no questioning. Not all therapies involve the radical questioning of the ‘presented world’, of course; very few therapies do, when it comes down to it! We are culturally indisposed to anything so threatening, anything so potentially disruptive. For most of us, radical questioning is the very last thing we want to get involved in and this resistance is reflected in our approach to mental health. Our approach to mental health is a deeply conservative one; it’s as if we imagine that the proper exercise of our innate conservatism (or ‘fear of the new’) can help us deal with the threat of the mental health conditions, even though the fear of risk-taking is in itself the root-cause of all neuroticism. Our conservatism means that we won’t question the ‘answers’ that we already have even though these answers don’t seem to be working so well. The assumption that we’ve made (without knowing that we’ve made it is) that the state of good mental health can be attained without stepping out of the conceptually-mediated world that we don’t know we are in. We believe that we can be mentally well in ourselves and hang onto our unexamined assumptions, which is a perfect example of ‘wanting to have our cake and eat it’.

At the present time the established mental health industry operates on the basis of the assumption that we can treat neurosis by swapping one bunch of ideas for another. The ideas we currently have (as sufferers of anxiety, depression, OCD, etc.) are seen as being ‘dysfunctional’ or ‘maladaptive’ and so the answer (we say) is to replace them with ideas that aren’t dysfunctional, aren’t maladaptive. We might therefore call this ‘the technical manipulation approach,’ which is of course very much in keeping with the hard-headed rational-technological ethos of the age. No earth-shaking revolution in the way we see the world is needed, we say, it’s just a matter of ‘tweaking this’ and ‘tweaking that’ and everything can be made right again! So far it seems that the great hopes we have placed in this rather superficial approach are unfounded; whilst ‘fixing-type’ psychological therapies may – at the very best – give us a new lease of life for a while, the overall effect of our reliance on coping skills and suchlike is to entrench us even more in the ‘revolving door’ paradigm which is so familiar to everyone working in the world of mental health. The problem is that we aren’t really getting to the root of things, and we’re showing zero inclination to do so.

Actually, it has to be said we aren’t really ‘trying to get to the root of things’ at all – this is too major an undertaking and we don’t have the resources to do this even if we did have the interest (which we don’t). Even with our ‘brief therapies’ our mental health services are being overwhelmed by the demand. When we talk about ‘getting to the root of things’ with regard to our mental health we are traditionally speaking about psychotherapy, which rather than running from six or nine weeks takes years (if not decades) and no service provider wants to hear about this! This is why we have turned our backs on psychotherapy and have convinced ourselves that brief, solution-focused therapies and the like are the way to go. Within the past ten to twenty years however we have seen an upsurge in interest in what we might call ‘psychedelically-assisted psychological therapy’ – interventions that combine the use of psychedelic drugs such as psilocybin along with a short period of psychotherapy. Some of us might go so far as to see this as the future of psychiatry, even though we might not always be able to say this publicly. The use of psychedelic drugs would seem to have immense potential nevertheless and research is bearing this out. Jordan Peterson – who is often regarded as being rather conservative in his views – has gone so far as to talk about the radical notion of the ‘one-time only dose’, which is unheard of in psychiatry.

Under normal circumstances, as we have said, it is very hard for us to get any perspective on our own thinking. Even when we work hard on it this still takes a long, long time. To develop a meditation practise, for example, will take many years. Genuine change happens slowly, not convulsively, as Jung says. It happens organically not mechanically. The pertinent point about psychedelic ‘medicine’ is therefore that a dramatic change in the way in which we see that world happens very quickly indeed – within the space of an hour or two so we can find that all our unconscious mental constructs have been rendered painfully visible to us as being ‘arbitrary mental constructs and nothing more’. The unseen machinery that creates and maintains the conceptually-mediated world has been disabled for the duration of the experience and from an existential point of view this is the most shocking thing that could ever happen to us. The rug has been pulled out from under our feet big time and there is no way that this isn’t going to be shocking. We would generally go to great lengths to avoid existential shocks such as this; this isn’t usually a pleasant experience since we feel that we are losing everything that makes sense to us, everything that seems reassuringly real and tangible. In one sense – of course – we are losing everything that makes sense to us, everything that seems real to us, but the critical point to understand about this is that what we are losing was never real in the first place. We are losing our illusions, in other words; we are becoming ‘disillusioned’. Although this is almost inevitably a painful business, it is all the same nothing if not wholesome. Growth is painful, change is painful, gaining wisdom is painful, but that doesn’t mean we should shirk the path that potentially brings all these benefits. We can’t grow as human beings if we refuse to leave the play-pen of consensus reality.

We lose our ‘supportive infrastructure’ – the infrastructure that has been provided for us by thought – but we do gain something instead (even though ‘gain’ isn’t quite the right word here because it was there all along). What we ‘gain’ is the perspective to see that’s the thoughts and beliefs we had about reality aren’t true at all! To put this another way, what we gain is access to intrinsic space, which is what remains when thought’s simulation of reality (i.e., the conceptually-mediated view of the world) has been disabled or switched off. We can’t relate directly to intrinsic space; we can’t measure it, detect it (or ‘prove it’ in any way!) but we do nevertheless have something that we didn’t have before, which is the capacity to change or grow. Concrete stuff doesn’t help us to grow, it’s intangibles that do that! According to Ngakpa Chogyam,

Learning to trust Intrinsic Space, the space between ‘known’ areas of experience, is the basis of growth – without it we stagnate.

We automatically assume that being able to know the world and ourselves in a ‘thought-mediated’ way is an indispensable advantage but it isn’t; it isn’t an advantage because what we ‘know’ are our thoughts about the world not the world itself, and because our thoughts about the world (our mental representation of it) are going to form a static picture, a ‘freeze frame’ of what’s going on, this traps us in a view of things which is utterly untrue, utterly without foundation, but which we are nevertheless absolutely convinced about. It is precisely our ‘knowing’ that so very effectively imprisons us in a world that will never allow us to grow, therefore. We are – culturally speaking – completely committed to believing in what rational thought tells us since we understand rational inquiry to be the only reliable way to gain information about the world. We imagine this to be ‘the scientific approach’. There is however nothing remotely scientific in confusing the world with our theories about it!

The only way therapy (if we allow that there is such a thing) can ever happen is when it involves going down a fully-fledged rabbit hole, therefore. There is no other option – the rabbit hole (which corresponds to the ‘Hero’s Journey’ that Joseph Campbell talks about) is the only thing that is going to help us. Our current approach in psychological therapies is however to have nothing whatsoever to do with rabbit holes, therapeutic or otherwise. When we go down a rabbit hole then everything gets turned on its head, after all, and how can that be expected to help us? We are – in all probability – confused enough already so how can getting even more confused than we already were do us any good? We don’t like rabbit holes because they are just too risky – they aren’t part of our nice safe ‘consensus reality’.

What we don’t see however is that we were confused all along; we were deeply confused all along but just didn’t know it. As Jung says, we have confused the product of the thinking process with what is being thought about, and what could be more fundamentally confusing than this? A therapeutic protocol that ‘makes sense to the rational mind’ is no help to us at all since all this does is to confirm that our way of looking at things is the right way. To have our static view of the world falsified, on the other hand, does us a world of good even though we don’t like it! We stand a chance of relating to actual reality this way, and it is only by relating to actual reality that we can ever change. When we are stuck in the world of our thoughts, meaningful change (which is to say, an ‘increase in perspective’) is a complete and utter impossibility…

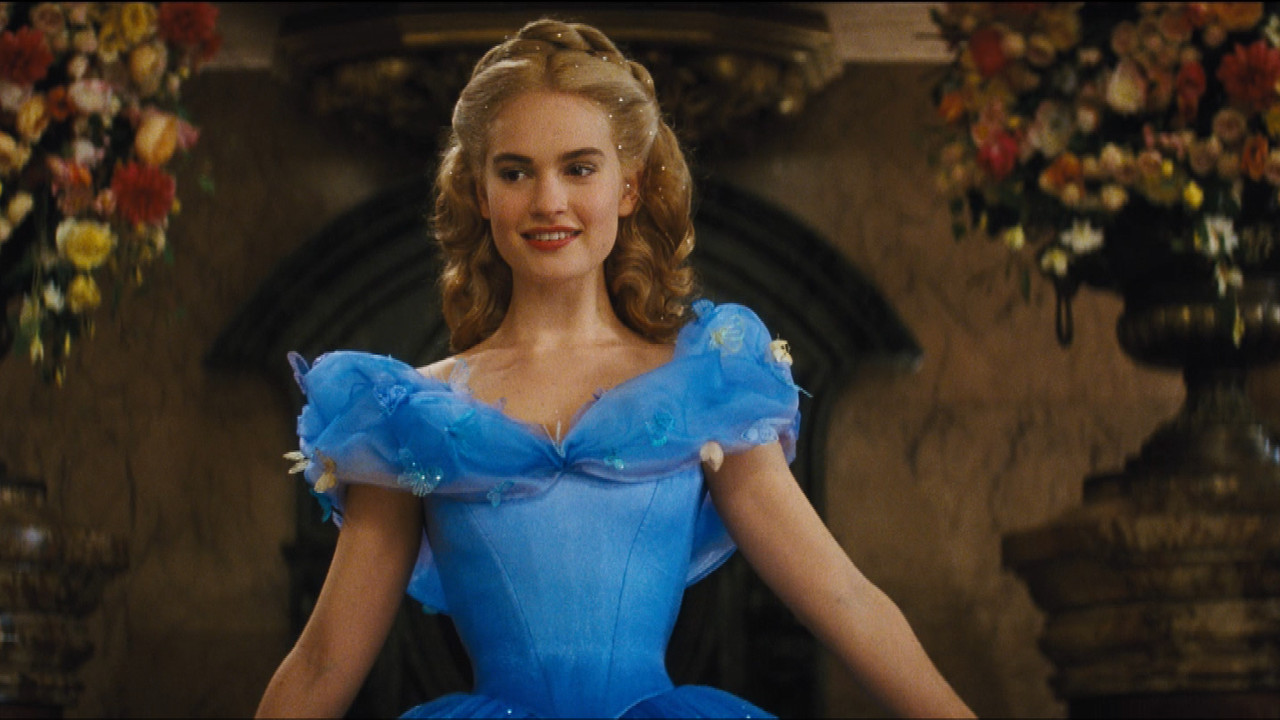

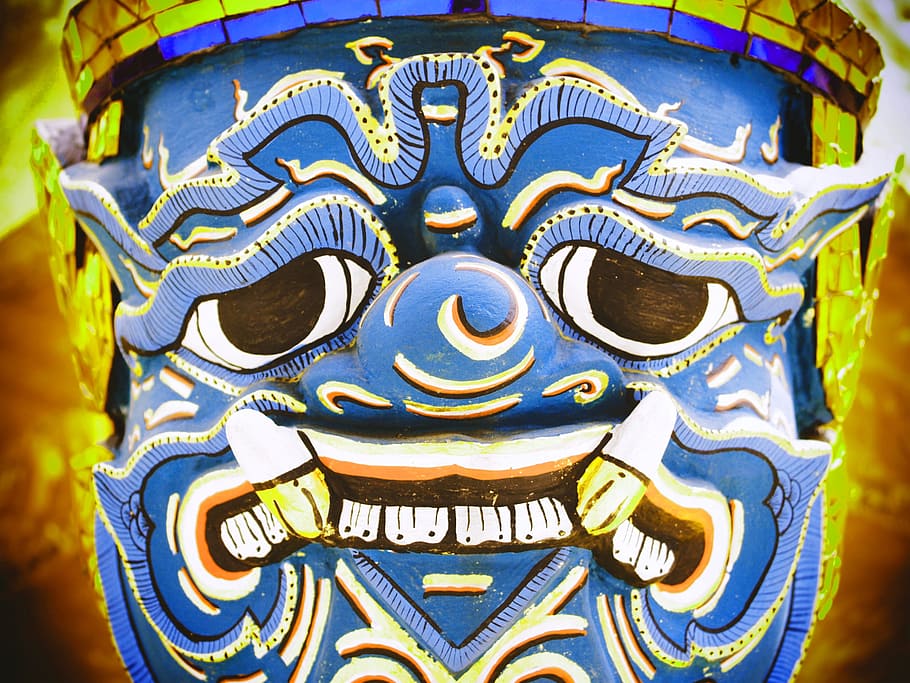

Art: wall.alphacoders.com