The quintessential action of unconsciousness is the action of ‘us trying to mould the world to our ideals or standards’. This is how we stay safely unconscious – by continuously doing our very best best to organise the world around our ideas of how it should be. Jung talks about the task of social adaptation in pretty much the same way, saying of it that –

This task is so exacting, and its fulfilment so advantageous, that he forgets himself in the process, losing sight of his instinctual nature and putting his own conception of himself in place of his real being.

Unconsciousness can thus be defined by saying that it is when we substitute our conception of ourselves for our real being, but we could also define it by saying that it is where we put our conception of the world in place of the world that is there already, the world which is not a product of the ubiquitous thinking process. It is the very same act of substitution that we are talking about in both cases – the non-generic is being replaced by the generic, the unprecedented is being replaced by the precedented, the unique is being replaced by the formulaic.

This is an ‘exacting task’ – we might say – because the ideal never can be fully realised; the precisely defined value that we are aiming at can never be fully realised because nothing real can be exhaustively defined. This is the key point about reality – everything is connected in the real world (as opposed to the hygienic world of our thoughts) and so there are just too many influences. To define one thing might not seem like too tall an order but if every single thing in the world is in a state of relationship with every other thing then this makes our task an incalculably bigger one than we would originally have believed – sooner or later we will realise that we’ve bitten off more than we can chew! We can’t get to grips with any apparent ‘part’ without finding out later on that we’ve taken on far more than we bargained for…

This problem doesn’t arise in everyday life because we never have to be that precise – we’re able to say ‘good enough’ and walk away and this is why we don’t get stuck to every little job that comes up. We don’t insist on being 100% accurate and so everything is fine. It’s only when we drift in the direction of perfectionism (or obsessionality) that we get into trouble – we then get too serious about getting everything exactly right (or being absolutely sure of things) in this case and this need for precision is what sinks us. This is what sinks us because in this world we never can be sure of getting something ‘100% right’, and the attempt to do so results in us grinding to an abrupt halt.

Perfectionism is suffering because nothing ever can be perfect (at least, not in the sense that we generally mean it); what we mean by perfect is precisely that there is an exact match between the specified ideal and the actual situation and obtaining this match is one of life’s great impossibilities. We’re ‘headbutting the universe’ here and so it’s us that’s going to come away with an almighty headache, not the universe. To make the ideal into the true is the Holy Grail of the thinking process and we lose all our good sense in our heedless pursuit of it – no matter how many times we knock ourselves out enthusiastically headbutting the iron anvil of reality, we will always keep coming back for more. We are chasing suffering with great energy and determination, in other words…

When the Buddha said that existence is suffering (or frustration) he didn’t mean that there is anything wrong (or anything lacking) with (or in) reality; this isn’t just a fancy way of saying that ‘everything is crap’, therefore. The suffering doesn’t come from reality but from us trying to make it be what it isn’t and what it never could be. As we have just said, when we fall into the trap of perfectionism then we’re hunting for something that just doesn’t exist – what we see as being ‘perfect’ or ‘the ideal’ is when we get reality to be exactly as we envisage or predict it; the situation that we’re chasing here isn’t ‘perfect’ therefore but merely unreal. Our endeavour is an absurd one, we could say; it is absurd because instead of letting things show themselves to us as they are, we insist on violently shoehorning them into our laughably crude mental categories and ignoring all the ways in which this doesn’t actually ever work.

Our ideas regarding what we think reality should be are frankly absurd and so even if we could get them to become true this wouldn’t in any way benefit us. We might well wonder why on earth we would want our incorrigibly dumb ideas about ‘what reality should be’ to come true – it is the fact that they never do (and never can do) that saves us from our foolishness. Since all our ideas about the world are inevitably going to be ‘crass oversimplifications of the genuine thing’ what we are actually doing with our thinking and theorizing is to degrade reality – we degrade reality and yet at the same time we fondly imagine that we are improving on it…

In one way – in a highly perverse sort of way – the fact that we can never, ever obtain the ideal actually suits us very well; it suits us because the futile task which is ‘the chasing of the ideal’ absorbs us completely and thus prevents us from being aware of anything else. Our effort to turn reality into what we think it should be proves to be ‘the greatest distraction ever’, in other words; it’s the greatest distraction ever just so long as we never see the truth of what’s going on, and we never do. We are kept busy on a full-time basis trying to get things to accord with our ideas for them, and the crucial point about this particular struggle (which is the polar struggle of ‘good against evil’, ‘right against wrong’, etc) is that it will absorb how attention just as a wad of blotting paper will absorb spilt ink. No matter how much effort and attention we put into the futile task it will absorb it all (simply because it is futile) and it will keep on doing this forever. Seeing this would be no good at all of course (from the point of view of trying to create the perfect distraction machine) but the whole point is that we absolutely can’t see that we’re being duped and so we will keep at it indefinitely.

‘The chase is better than the catch’ because in this instance there simply is nothing there to catch – it is only necessary that we believe that there is something there, not that there actually should be. This means that we are obliged – if we want to continue with the game – to refrain from ever questioning or examining the standards or ideals that we are constantly projecting upon the world. This is why changing society (or changing the way we do / see things) isn’t as straightforward as we might think; if the glue that holds the whole thing together is us ‘never questioning the ideals that we are trying to enact’ (if ‘not-questioning’ is the strategy by which our whole world is maintained, and if it is the case the strategy only works when we remain profoundly unconscious of it) then how on earth are we ever going to be prevailed upon to ‘genuinely strive for change’? It isn’t just ‘difficult’ for us to work towards change as long as we’re in Unconscious Mode – it’s flatly impossible. That’s never going to happen. Basically, when we’re in ‘Unconscious Mode’ then we’re full of crap…

What we’re essentially doing when we’re in Unconscious Mode is that we are allowing ourselves to become wholly preoccupied with completing a task that never can be completed whilst at the same time making sure that we never gain any insight whatsoever into this fact. ‘Not gaining insight into the true nature of the task that we’re engaged in’ is something that happens quite automatically when we keep our nose to the grindstone – we’d have to stop what we’re doing to see that. As long as we are being purposeful we won’t have any perspective on what we’re doing and because we have no perspective we won’t be able to see the counterproductive nature of our efforts. There is therefore zero motivation to change in this setup, only what we might call ‘theatrical motivation’ (which is to say, the motivation to distract ourselves with ‘the illusion of change’). Theatrical motivation is our means of deceiving ourselves on an ongoing basis; it is – we could say – where we pretend to ourselves that we’re motivated to do something when we’re totally not! Because our basis is unconscious self-deception there is therefore absolutely no way that anything true or real or wholesome can come out of it. This is par for the course since in the Unconscious Realm – as we would know if we weren’t so immersed in it – ‘everything is for show and nothing is real’.

Once we grasp this basic point then we can understand why it is that no one ever gets very far in this world of ours by speaking the truth – we’re going against the grain big time if we do this and no one’s going to understand what we’re trying to achieve by being so difficult. People will be genuinely confused at our perversity – they will have no ability to relate to us. When we’re in Unconscious Mode then the whole current of things is to move away from the truth whilst at the same time creating the persuasive illusion that we are moving towards it, which allows us to say to ourselves that we’re embracing the truth, rejoicing in the truth, celebrating the truth, and so on and so forth. And we’re not just saying it either – we honestly perceive it to be the case and we would be shocked to the core if we were to see what the actual situation is (which is that we are 100% committed, on a permanent basis, to moving away from reality). The movement towards our goals is always a movement away from reality.

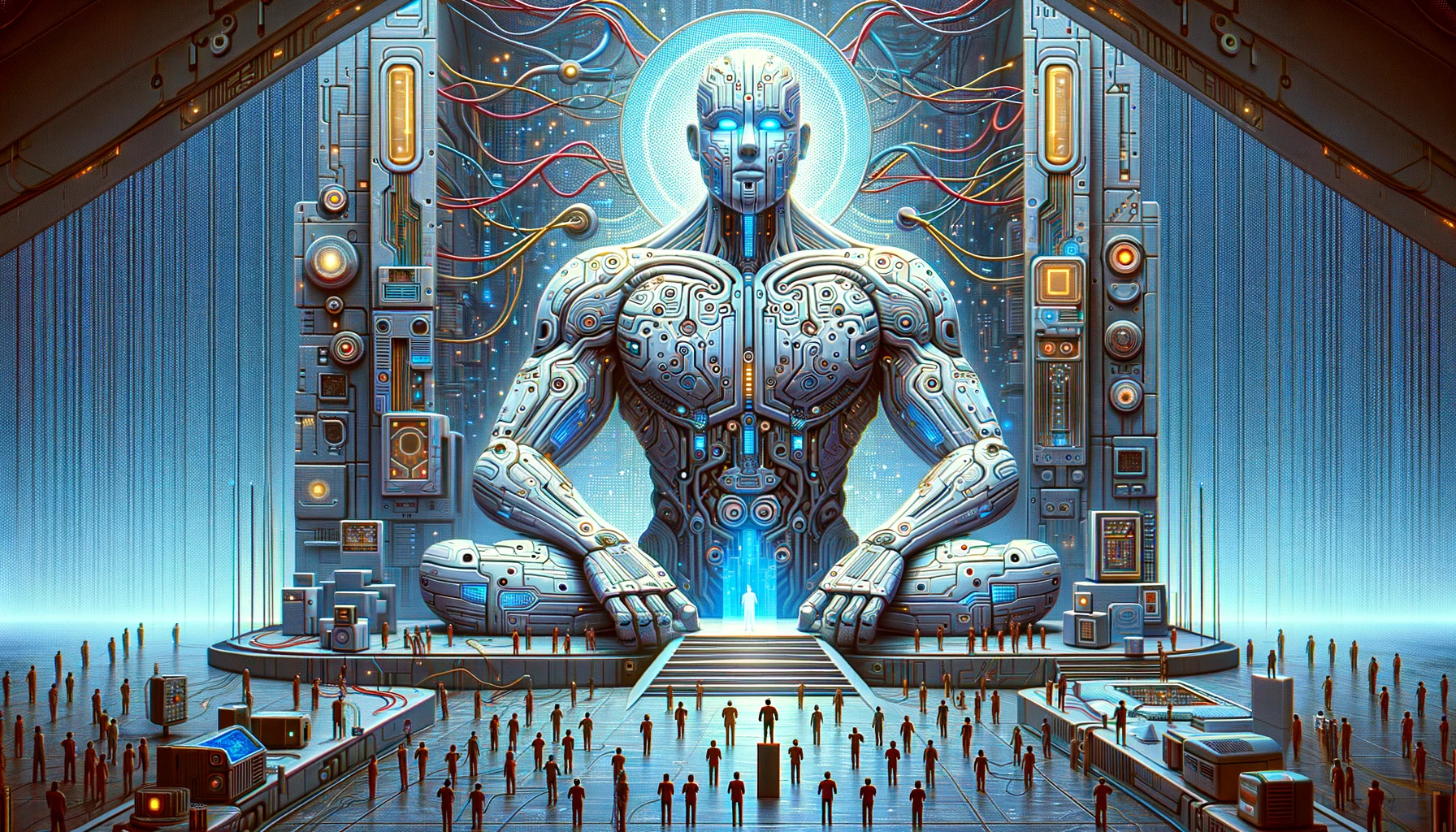

Whenever we try to shape or modify the world in accordance with our thoughts then we are moving away from what’s real and heading instead into the world of illusions. Our thinking takes us by express train into The Realm of the Abstract and The Realm of the Abstract (as its name implies) isn’t an actual place! Rather than being an actual place, it’s a projection of the rules that we have lodged in our head; this Projected World – because we have no recognition of its true nature – proceeds to act on us in a hypnotic manner, causing us to imagine that we have free will when we don’t, causing us to believe that we know what’s going on when we don’t. Although the force that is acting on us is purely mechanical, like a marble rolling down a chute, we perceive it to be conscious, a bona fide expression of our autonomy, our self-directedness. This therefore is the phenomenon of ‘identification’ – we mistake impersonal mechanical action for our own free will, just as we mistake the bland generic image that thought provides us with as ‘who we truly are’, and the consequence of this ‘tragic-comedic misidentification’ is that our lives are spent being the helpless, clueless slaves of thoughts (or ideas or beliefs) that don’t actually mean anything.

Image – peakpx.com