The reason for us to be in Copying/Heteronomous Mode (as opposed to Creative/Autonomous Mode) is always the same – fear. Fear is what is behind this kind of business. Fear causes us to ‘live the script‘. Fear causes us to be ‘addicted to copying’, basically. We’re hooked on copying because we don’t dare to be creative; because we don’t dare to be original. We won’t ‘let go of the old’ because we’re ‘afraid of the new’…

Copying is how we protect ourselves against reality, it’s how we make sure that we never encounter anything that we can’t understand, anything that is radically unexpected. Out of fear we ‘stick with the known’, we stick with whatever it is we’re familiar with and we distrust and avoid anything we don’t know, anything that we’re not familiar with.

Copying Mode is the same thing as Conservative Mode, therefore – when we’re in Conservative Mode we talk about maintaining standards, preserving traditional values, protecting public morality, and all that kind of stuff. This paints us in a good light of course, but what’s really motivating us is the fear of anything new, the fear of having to change.

We don’t know what we’re doing here, we don’t know what’s going on. It’s not as if we ourselves came up with the idea of the strategy of ‘copying’ – it all happens quite automatically once we hand over responsibility to the perceived ‘need’ to escape whatever it is that we’re afraid of. We tell ourselves stories to validate what we’re doing, and we believe that story as soon as we hear it. We believe it as quickly as we do because we’re afraid, and we’re grasping at straws. We’re grasping at anything that comes along. Fear makes us ‘recycle the past’ and fear makes us swallow every story going, no matter how cliched (or transparently nonsensical) it might be.

When we’re in the grip of existential terror then we will believe whatever it is we have to believe in – no questions asked! Any story will do, no matter how banal, no matter how absurd or ridiculous it might be; we become entirely uncritical, we become so cravenly gullible that no matter what story it is that we’re told (or we’re telling ourselves) we will never have any problem believing it. Fear means that we have no curiosity about anything; it means that we’re in ‘the business of believing’.

A fearful mind is a believing mind and will believe whatever we have to, will believe whatever comes to hand. Believing is the name of the game. Beliefs have nothing to do with what the belief is about – the point in believing is ‘to have a belief’ and this has nothing to do with what we’re believing in. A believing mind is a closed mind and being closed is what protects us from ‘whatever might be out there’. Having a closed mind protects us from the Immensity and that’s all we care about.

To be open is to be vulnerable whilst to be closed is to be defended; to be open is to have no beliefs, no opinions, no idea of what it’s all about. To be open is an act of courage therefore – it’s an act of courage because we simply don’t know what is going to happen next. Anything could happen and we don’t know how ‘big’ that anything might be, we don’t know what it might entail. ‘Anything’, as we have said, is precisely what we’re afraid of…

We get around the problem of ‘being open to whatever might be out there’ by the expedient of recycling the past. We know where we are with the past – we ‘know what’s in it’, we know that we’re not going to get any surprises. The past is safe whilst the future – as Alfred North Whitehead tells us – is dangerous. Repackaging and recycling the past is the ideal solution to our existential terror; ideal – that is – apart from one thing – by reproducing the same thing over and over again and calling this ‘serialisation of the Known’ life – we create a nightmare scenario for ourselves. We create the most inimical situation that consciousness could ever face.

Switching into Copying Mode and repeating the same thing over and over (or doing the same thing over and over) so as to keep the Unknown away isn’t really an ideal solution – isn’t actually any sort of solution, but simply another way of suffering. Copying Mode is a long-drawn-out exercise in postponing the inevitable, ‘the inevitable’ being that moment when we’re going to have to come across something new. Copying Mode is how we fight against the truth, in other words; what we keep on repeating is ‘the Lie’ whilst what we’re trying to cover over (or drown out) with our aggressive mechanical repetition is the actual (non-mechanical) reality itself.

As we have said, our way of ‘not facing up to what we’re doing when we’re in Conservative Mode is to turn everything on its head by saying that what we’re doing is the right thing and that all other things are wrong. This is the oldest trick in the book. Although we’re actually stuck – and signalling this fact by going around in endless futile circles – we turn this around by saying that we’ve already ‘got’ it and because ‘we’ve already got it’ we don’t need to look any further. We can now justifiably close our minds because we have seen the truth and anything else (any new stuff) would threaten that truth. To protect or defend what we are calling ‘the truth’, all we need to do is ‘keep on fighting the good fight’. ‘Fighting against reality’ is thus normalized. It’s ‘the right thing to do’…

Robert Anton Wilson explains this idea with the story of the violinist who keeps on playing the same note out went over again, to the dismay of his long-suffering wife –

There’s an old Jewish story about a man who liked to play the violin. He had this habit, though—he kept playing the same note over and over. It amused him. Perhaps it gave him a deep ecstasy. But that was his shtick: he played the same note over and over. After several years, his wife finally got to the point where even her wifely patience was exhausted and she said to him, “Max! Max! For god’s sake, Max, other men who play the violin, they don’t always play the same part of the string. They play up and down the string, and they play on all the strings. And they make melodies, and they make counterpoint, they make sonatas, they make forms. Not the same note over and over.” And Max looked up from playing his one note and he said, “They’re looking for the place. I found it.”

This is what we all do – we’re all stuck in exactly this same way and we all go around not facing it and saying that our stuckness, our fear-driven conservatism, is us saying to ourselves that we’re ‘doing the right thing’. Society is our way of collectively self-validating, our collective way of saying that ‘we’ve got it right’ and not letting anyone tell us otherwise; it’s our way of perversely feeling good about ourselves when all that’s really happening is that we’ve fallen into the sordid pit of collective denial.

Anytime we feel ‘right’ (i.e., any time we feel that we are doing or saying the right thing, and experience euphoria on this account, elation on this account, then this is a surefire indicator that we are deceiving ourselves, or that we are allowing ourselves to be deceived. ‘Right’ doesn’t exist in the real world – it’s a thoroughly nonsensical concept and so we have no business in feeling euphoric, no business going around feeling as smug as we do. The euphoric glow that we’re experiencing doesn’t come from having achieved something worthwhile, but as a result of us successfully running away from the problem and refusing to admit that this is what we’ve done.

When we switch over into Copying Mode then we feel good about this since we’re avoiding the thing we’re most afraid of, which is change. There is obviously no change when we are involved in copying (or obeying, if we want to put it like that) instead, what we have is this thing called ‘getting it right’. Life itself becomes nothing more mysterious or intriguing than a matter of ‘getting it right’ – comparing ‘what we’re doing’ with ‘what we’re supposed to be doing’ (i.e., the template) becomes our way of knowing how well we’re doing. Life thus becomes all about ‘comparison-making’. There’s no creativity involved in Copying Mode (creativity being the antithesis of copying); when we’re in Creative Mode then there is of course no such thing as ‘right’ or ‘wrong’; ‘right’ and ‘wrong’ refer to the template and how good we are at obeying it, and in creativity there is no template, no standard, and- crucially – no attempt to ‘do well in the task of faithfully replicating it’. Alternatively, we could say that there is no freedom in Copying Mode – we’re not free to ‘not copy from the template’, after all. That is the one thing we are most definitely NOT free to do!

Copying Mode is Mechanical Mode – it’s the mode in which anything that happens, happens as a result of an external mechanical force being applied. Everything that happens has been caused, in other words. The ‘Meaning of Life’, when we’re in this modality of being, is simply ‘to do what the External Authority wants us to do’; the meaning in question can be resolved into two elements therefore – there is the element of reward if we get it right and punishment if we don’t (or praise if we succeed in blame if we don’t). This is what we might call Extrinsic Motivation – it is the type of ‘motivation’ that comes from outside of us and controls us every step of the way…

There isn’t a hell of a lot to be understood about this thing called Extrinsic Motivation – it’s as crude as can be, as crass as crass can be. There isn’t anyone in the world who doesn’t understand this basic principle – we learn compliance to the rules very early on in life, we learn it and very quickly forget that there is (or could be) any other way. Extrinsic motivation is usually camouflaged in one way or another; it has to be disguised as something ‘virtuous’ because it’s such an unpleasant and unworthy kind of thing. Copying Mode – we might say – two things: it involves [1] The application of mechanical pressure from the outside, plus [2] The special ingredient of self-deception. In short, we are externally compelled in everything we do but – at the same time – we turn this around and say that it was us who wanted to do it all along. Or we might say that ‘it’s the right thing to do’, which comes to the same thing. We’re excusing our lack of courage or initiative with ‘false virtuosity’.

Instead of perceiving it to be the case that we are ‘being rewarded for doing what thought says we should do and being punished for not doing it’, we see this as ‘us feeling good because we have succeeded’, or as ‘us feeling good because we’ve done the right thing. And if we are critical of ourselves, blaming of ourselves, totally down on ourselves, etc., then we still persist in believing that this is our free or volitional behaviour, even though experience shows that we are utterly incapable of not engaging in it (which should really give the game away). We are extremely resistant to seeing that these thoughts aren’t under our control and that it is not the case that we are ‘choosing’ to be self-critical or self-hating but rather that it is just all ‘happening mechanically’ and we are passively identifying with the rules that are governing the situation. Under normal conditions – when things haven’t gone to an extreme – we will almost certainly never see this.

Our subjective experience of the situation is that we are not being operated like a puppet from the outside, therefore. All the responsibility for what happens is ours, as far as we’re concerned, and we will suffer (or feel good) accordingly; if we get it ‘right’ then it’s all due to us and if it ‘goes wrong’ then that’s ‘all down to us’ too. Thought creates both the euphoric and dysphoric self; as Krishnamurti says,

The thinker is a fictitious entity, an unreal state. There is only thought; and the bundle of thoughts that creates the ‘I’, the thinker.

The thinker – the one who does the thinking (and who does all the rest of the stuff too) – is just another thought however, just another ‘projected idea’, and thoughts (or ideas) aren’t volitional entities. The thought of ‘who I am’ is just a ‘description’ or ‘notation’ (it is ‘a robot that carries my name’, so to speak) and as such it cannot possess free will. It’s my ‘avatar’ – we might say – but it’s an avatar that only does what its conditioning tells it to; without its conditioning (i.e., without the rules that ‘tell it who it is’ and ‘what it likes and doesn’t like’ the conditioned self doesn’t get to exist.

Our idea of ‘who we are’ has no free will, the ‘ego-construct’ is has – as we might expect – no freedom to anything other than what it has been set up to do in advance. It cannot ‘act’, it can only react. It can only behave in the way that it has been given to behave. We could interject here and say, ‘Oh – does this mean that everything is predetermined and that there is no such thing as free will?’ but this question – if we ask it – would be part of our confusion – ‘thoughts’ (or ‘constructs’) don’t have free will, and it’s bizarre that we should think that they should! It’s not that there’s ‘no such thing as free will’ but rather that there’s no such thing as ‘free will for a thought’, ‘free will for an idea’, ‘free will for the image that we have of ourselves’. We go along with some idea, some notion of identity, and we say ‘Yes – this is who I am’ when it isn’t at all and then we are either euphoric or dysphoric because this phoney idea of who we are, this artificial construct, either ‘does what we falsely imagine we want it to do’, or because it ‘fails to do what we imagine we don’t want it to do’. We don’t want anything really however – our conditioning tells us ‘what we want’ so there’s absolutely no reason why we should feel good about this bias being realized (or bad about it not being realized).

We can’t have our cake and eat it – ‘having the cake’ translates as ‘obtaining ontological security’ whilst ‘eating it’ equals ‘being free’ (or ‘being able to freely participate in life’). Being able to freely participate partake in life sounds straightforward enough – and in one way of course it is – but in another way it’s the most difficult thing ever. It’s ‘the biggest challenge ever’ (which is of course is only what we’d expect). Life is a terrible challenge for us – it’s a terrible challenge because in order to live we have to relinquish all of our spurious control and this just happens to be the one thing we never want to do… In order to live we have to risk – ‘living is risking’, we might say. To live is to risk but fear puts the breaks on this; fear puts the breaks on this big time – fear means that we can’t let go of our ‘prior state of being’ to see what happens next, and – instead of doing this, instead of taking the risk that is existence itself – we opt to repeat the limited pattern we know and are familiar with, even though this way we’re never going to discover who we really are…

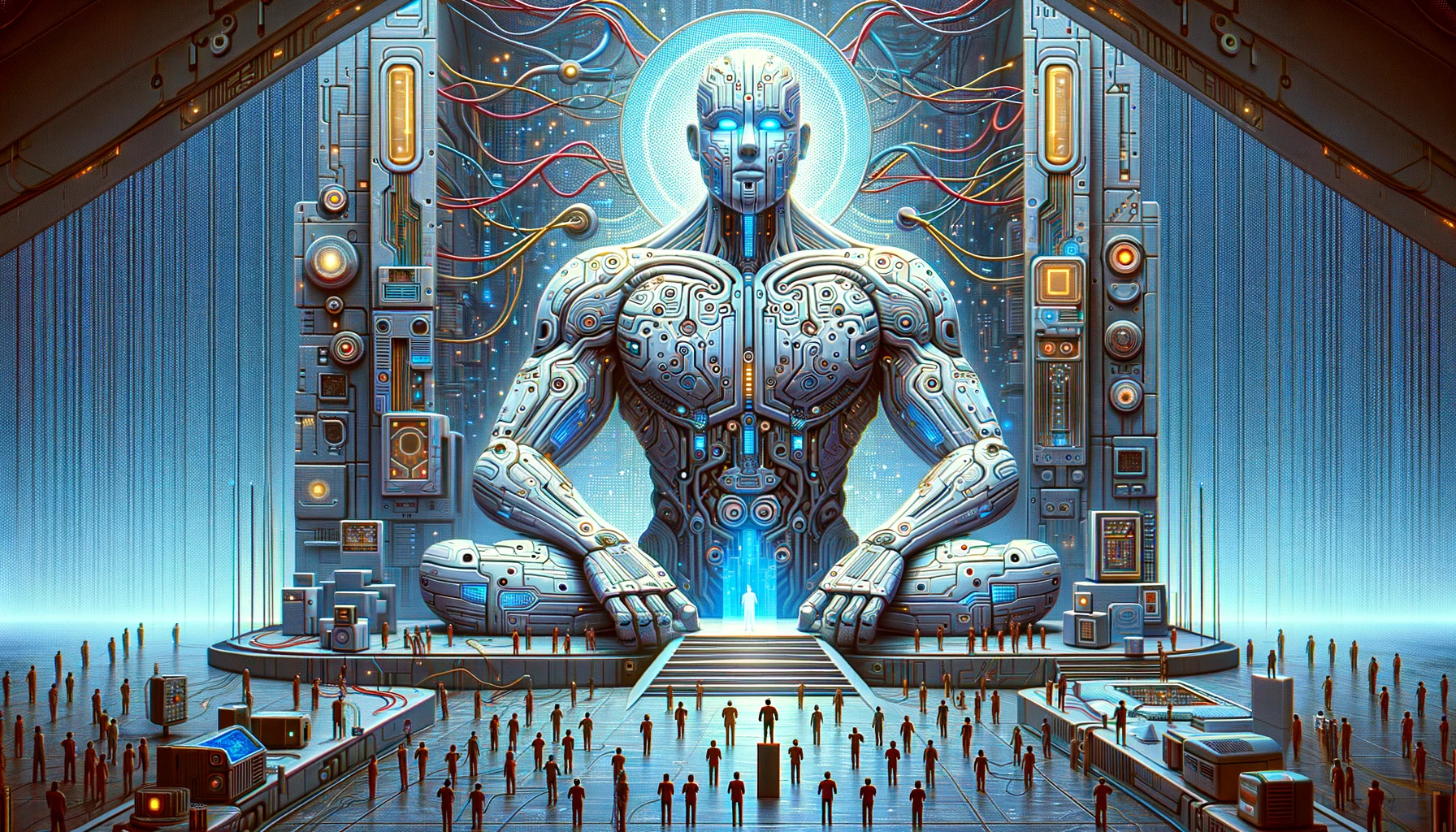

Image – peakpx.com