We come out with all sorts of impressively sophisticated theories to explain anxiety – it is as if we hope to frighten the anxiety away through being so very clever – but none of this is going to do us any good. The reason it is not going to do us any good is because that our sophisticated approach is really nothing more than ‘the intellectual mind at work yet again’ and the intellectual mind creates anxiety as a by product of its function, just as the operation of a diesel engine produces exhaust fumes, so we’re not going to help matters no matter how smart we get about it. Being ‘super-smart’ about anxiety isn’t the answer, which is more than just a little bit hard for us to understand since we think that being clever about things, and being clever life about in general, is the pretty much the way forward. If it proves not to be the way forward then we’re in trouble! In a nutshell, the reason thought can never help us understand anxiety is because anxiety is a direct result of us believing in hard-and-fast boundaries (or edges) between things, and the way thought works – the only way it can work – is by assuming the existence of these boundaries. Put like this, it becomes very clear indeed why ‘thinking about anxiety’ isn’t exactly going to help us a lot!

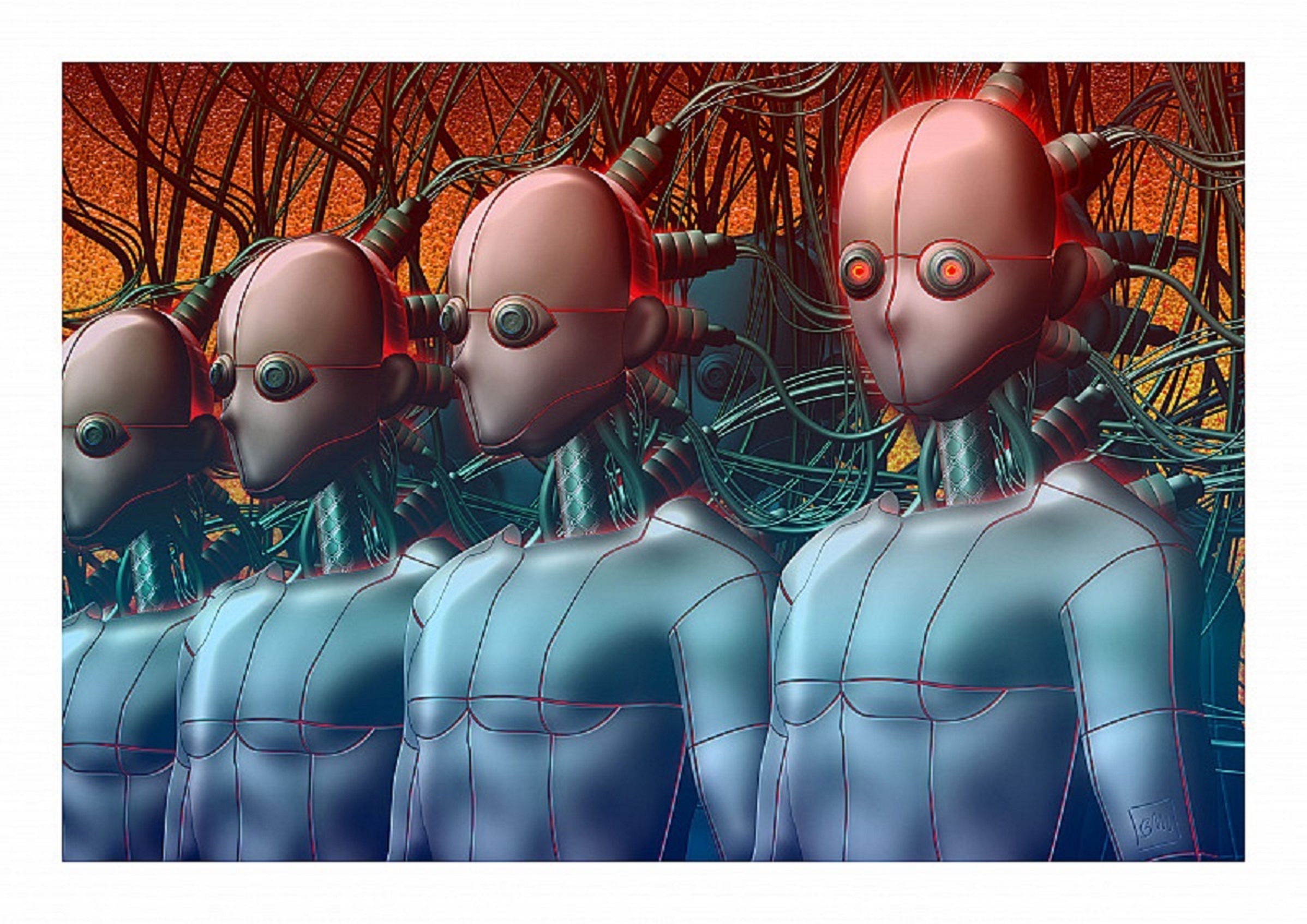

A good way to explain anxiety (along with all the other neurotic conditions) is to say that it is the inevitable consequence of the ‘loss of autonomy’ that always takes place as a result of us constantly over-thinking things. We rely too much on rational thought and this makes us anxious. ‘Autonomy’ – in the psychological sense’ – means that we depend on external factors (our ideas about life, our habits and distractions, our mind-produced coping strategies, our ‘systems’, entertainment, other people who believe the same things as us, society in general, technology, etc) in order to feel ‘OK’. As soon as we say this it becomes clear (if it were not before) that the whole movement of rational culture is in this direction, is in the direction of ‘increasing reliance on external supports. We’re becoming more and more heteronomous, as Ivan Illich puts it. We making everything be ‘on the outside’ and at the same time we’re impoverishing (and ultimately eliminating) what is ‘on the inside’. We’re creating a ‘consensus rational world’ and then we’re living in that world, in other words, and this is heteronomy in the most extreme sense of the word.

This proposition – the proposition that anxiety is a consequence of decreased autonomy – doesn’t really need a huge amount of explanation. We don’t have to write books about it. It hardly needs any explanation at all – if I am dependent upon some sort of external support for my sense of security or well-being then this doesn’t result in anxiety, it is anxiety. This is anxiety in a nutshell. Just as soon as we put ourselves in a position where we are relying on an external factor in order to feel good about ourselves then anxiety is born –it might not immediately walk out into centre stage, but it’s there waiting in the wings. Anxiety is now a player in the show…

The state of heteronomy (which equals ‘the state of relying on artificial comfort zones’) is not visibly the same thing as anxiety – really what we’re talking about here is the manufacture and maintenance of a false sense of well-being or security and the whole point of a ‘false sense of all being well’ is that whilst this isn’t actually the case we do nevertheless feel that it is, and this makes us feel OK. When the comfort zone is working well we feel that ‘all is well’ and so we aren’t visibly (or consciously) anxious. We live in a world where we have a very superficial sense of all being well but because we don’t see this world as being very superficial we think that everything is perfectly fine and as it should be. ‘Invisible superficiality’ equals (of course) ‘latent anxiety’ – it is ‘anxiety waiting to happen’. Just as long as we remain comfortably unaware that our sense of well-being is only a paper-thin kind of an affair with nothing behind it then we’re going to say that we don’t feel anxious. We’re going to pooh-pooh the idea that we’re suffering from latent anxiety. This ongoing perception or belief that we’re fine and dandy is contingent with the lack of awareness regarding the entirely theatrical nature of our supposed well-being, therefore. This puts us in a situation where ‘us being aware of our situation’ is always going to be synonymous with ‘us becoming anxious’. Awareness actually has become ‘the bad guy’, in other words, although we cannot of course ever come close to actually admitting this to ourselves. This put us in a very strange situation indeed therefore, even though we can’t for the life of us see it.

This is counter-intuitive to say the least. Such a way of looking at anxiety is a far cry from our usual perspective, which is as we have said super ‘top-heavy’ intellectual. We tend to see anxiety as an aberration or error or glitch in the system which can be dispelled (or at least moderated) by looking at things clearly’. All we have to do is get ‘rational’ (or ‘objective’) and the anxiety we feel will start to go way – naturally it will go away because its only there as a result of us seeing the world in a distorted or erroneous way. But what we’re saying here is completely contradictory to this viewpoint – we’re saying that anxiety comes about as a result of dawning awareness, not as a result of a lack of a proper or realistic perspective on the matter. Anxiety comes about when we see our true situation, and so in one sense we’re actually right to be anxious! We’re seeing through our mind-created comfort-zones and that isn’t a pleasant experience, to put it mildly. Nothing is worse than suddenly starting to see how we have been deceiving ourselves – nothing is harder than seeing the truth when the truth is something that we have preferred to obscure…

We don’t see ourselves as we are at all, as Gurdjieff says. We imagine ourselves to be orientated towards truth, orientated towards awareness and this is of course a nice image to have about ourselves. We imagine that we are favourably disposed to finding out about life and the universe, that we are a culture of intrepid intellectual ‘explorers’ and that our natural orientation is towards to ‘the light’ rather than to the darkness of superstition and irrational belief. We pride ourselves on this. But we’re not favourably inclined towards ‘finding out the truth’ at all – that’s the last thing we want to do! We operate in the darkness of psychological unconsciousness and that’s how we intend to keep it – instead of awareness we have this type of a thing that we could call ‘fractional consciousness’, which is consciousness when it believes in the arbitrary constructs of thought (when it can’t see through our ideas about the world, in other words). We aren’t orientated towards ‘truth’ or ‘awareness’ at all – we’re orientated towards the black-and-white mind-produced picture of what the world is all about, which is the rational mind’s own version of the truth. This version of the truth only holds up when we’re not conscious, so really we’re orientated towards the ‘lack of awareness’, and this orientation of ours is evident in everything we do. We’re not getting happier and wiser with our so-called technological ‘progress’, we’re becoming more and more absurd, more and more miserable, more and more selfish or ‘narcissistically blinkered’ in our view of things. There never was a less edifying picture of what human beings are capable of. Although we will still meet individuals who are free, to some extent or other, the structures and systems that are in place (the government, religion, the educational system, the workplace, the media, and so on) are wholly orientated towards mechanical ends and it is to these ‘mechanical ends’ that we are being funnelled, en masse. This – as reluctant as we might be to see it – is what society is – it’s ‘a funnel directing us towards a mechanical end’.

It does of course suit society for us to be funnelled in a mechanical direction. When we see things from the mechanical point of view regimentation makes perfect sense, but what makes sense on the mechanical level doesn’t make sense on a human level, as we would all know very well if we were to actually think about it. The psychologically deleterious side-effects of social adaptation have been very clearly expressed by Jung over eighty years ago when he said… , but these days this is not something we show much – if any interest it. As far as modern psychology is concerned the deleterious side-effects of social adaptation is very much the ‘woolly mammoth in the living room’ – we might keep on walking into it but we certainly aren’t about to start mentioning the fact. We make out that we’re interested in other things. When we are regulated and mechanized by society – so that we think and act in more or less a generic fashion – then this is not just a factor that acts against our mental health, it is the root cause of much of our neurotic suffering. Living generically means that we aren’t taking responsibility for our own lives; we’re copying from an ‘external template’ so that we don’t – as the saying goes – have to think for ourselves. We’re handing over our freedom to a ready-made pattern or system, we’re swapping autonomy (which is hard work) for heteronomy, which is like buying a ‘paint-by-numbers kit’ from a high street shop instead of learning to paint properly and discovering our own unique style, that style that no one can come up with but us. Discovering our own voice instead of adopting a generic one is hugely harder work, but it is nevertheless not really something that can be meaningfully substituted for. We’re fooling ourselves if we think that it can.

Adopting a generic voice instead of discovering our own is classic pain-avoidance and it is pain-avoidance that lies at the heart of neurotic suffering – we avoid the authentic pain and are therefore compelled to suffer inauthentically instead! Instead of embracing the challenge of the Hero’s Journey (to use Joseph Campbell’s terminology) we go for ‘the easy option’ (or cowardly option) of ‘refusing the call’ and as a result of this avoidance we get locked into the sterile suffering of ‘the negative adventure’. This is what the negative adventure is all about – instead of facing the challenge of living our own life creatively or authentically (which is a type of ‘energizing’ or ‘dynamic; pain) we endure the humiliatingly pointless pain that is our daily fare when we lead the generic life. As we started off this discussion by saying, although having everything provided for us by some external authority that we can place all our trust in feels very comfortable to start off with, this comfort is only a superficial veneer that masks untold depths of misery. Comfort is another word for suffering, just as pleasure is another word for pain. As we also – and equivalently – said, dependence upon our tried-and-trusted comfort zones doesn’t just engender anxiety, they are anxiety. Our beloved comfort zones are anxiety in its latent form.

This is of course something that we are particularly resistant to seeing – when one of comfort zones starts to fail us we do not make the jump of seeing that this is in the nature of all dependencies, all comfort zones, we assume that it is just a local fault and we try to remedy the situation by finding a better comfort zone, a more reliable one. In essence, the comfort zone that we are looking for is the feeling that what we are doing (or the way that we are doing it) is right, and so when we try to fix or correct anxiety by labelling it as being ‘an error’ and looking for the right way to function instead all we are doing is looking for a better comfort zone. To believe that there is a right way to do things, a right way to see the world, is simply a belief in an external authority (i.e. the external authority of the rational mind’s framework of reference) that can tell us what is right and what is wrong. To talk in terms of errors or controlling or fixing is just us looking to put our trust in an external source of authority, so that we can just do whatever that authority tells us to do. We’re desperately trying to hand over all responsibility, in other words. Abdicating our responsibility for how to relate to the world or to ourselves to some convenient generic formula is what creates the anxiety / dependency in the first place, yet we also imagine that this can be the cure.

There is therefore an inherent glitch in our crude ‘mechanical’ way of seeing anxiety: just as long as we see as anxiety (or anxious thoughts) as being an error, as an incorrect way of seeing the world, then our only course of action can be to try to fix or correct this error. If we see anxiety as being the result of seeing the world ‘the wrong way’ – as we do – then this implies that there is ‘a right way’ to see it and this straightaway gets us locked into a polarity, which is itself anxiety-provoking. Polarity (i.e. the sickness of right versus wrong) is what creates anxiety in the first place so polarizing matters even more certainly isn’t going to do much to help us. If there’s a wrong way then there must be a wrong way and so the more money we put on getting things to be the right way rather than the wrong way the more anxious we’re going to be about messing up. ‘Following rules’ isn’t going to cure anxiety because anxiety is implicit in rules in the first place, in other words. Rules don’t give us any leeway – rules make an absolute demand on us that things should be one way and not the other – and whenever there is no leeway, whenever there is an absolute demand being made on us, there is always going to be a fear of not being able to accord with the demand. This is what fear is – it’s the flip-side of a rule that we can’t question. Fear turns into anxiety when we deny it and we deny the fear of ‘not being able to get it right’ by putting lots and lots of effort into getting it right. The problem with this is that the belief that we can now get it right has become our ‘comfort zone’, and – as we keep saying – at the same time we create a comfort zone we also create anxiety. When we are able successfully believe in our comfort zone (which means not seeing that it is a comfort zone) then the anxiety is latent or invisible and we feel that all is well with the world; as soon as awareness starts to come back into the picture however and we start to suspect that we’re only feeling good because we have successfully deceived ourselves, then the latent anxiety (the anxiety which was always there) starts to come to the surface…

When we’re caught up in anxiety then it’s a slippery slope – it’s a slippery slope because we use rules to try to get out of the anxiety. The rule we use is the rule which says ‘there must be no anxiety’ and we start using this rule we fuel the anxiety even more (because we’re saying that we’re not allowed to feel anxious) and the only way we can think of to deal with this exacerbated anxiety is by introducing yet more rules, yet more stipulations, yet more biases. We have rationalized our anxiety, and by doing so we have potentiated it to the nth degree! Our assumption – the assumption that we always make – is that there must be a right way to see reality. This is the assumption that we can’t ever question because if we did question it then we’d have to admit the possibility that it isn’t actually possible to hand over all responsibility to some external framework of reference. We’d have to ‘take back our freedom’ in this case, and that is precisely what we don’t want to do. Our insistence that there must be a right way to see reality is the very same thing as our refusal to reclaim our own freedom to relate to reality in a spontaneous way, in a way that hasn’t been predetermined by some mechanical system.

How could there be such a thing as ‘a right way to see reality’ or ‘the right way to see the world’? What an absurdly nonsensical supposition this is. If there is a right way to see reality then there must be some external framework in place – like the scaffolding around a building that is half-way through being constructed – that we can use to orientate ourselves with. Reality would have to be embedded within some map of reality, in other words, which would means that the map or model comes first and reality a very poor second. This is however getting backwards – maps and models come out of reality and not vice versa! To insist – as we are insisting, whether we can see it or not – that the map, the rational context has to come first is pure laughable insanity – this is epic stupidity, stupidity on an unsurpassed scale. There can be such a thing as right and wrong but right and wrong come out of reality on a secondary because – they do not come before reality, they do not inform reality, they do not tell reality what it should be doing. The assumption that reality itself could either be ‘right or wrong’ is ludicrous in the extreme – right or wrong in relation to what we might ask? Some signpost or measure or framework that we have randomly pulled out of nowhere and then stuck up on a pedestal, something that is itself not reality (because it is outside reality) but which nevertheless somehow manages to have more authority than reality? As crazy or nonsensical as this may sound, it is precisely what we are saying. This randomly selected framework (or context) is what we have handed over our freedom to; it is what we have handed over all responsibility to and thereby made ourselves dependent upon. This signpost or yardstick or measure or framework (or whatever we may want to call it) is nothing other than the rational mind.