Suchness is the perception of the world as it is in itself, which is not something we ordinarily have much if any interest in. Ordinarily, we’re not interested in the world as it is in itself but only in what we can make of it (or only in what we can take from it, if we want to put it like that). Everything is about the exploitation of the world (i.e., what it can do for us) rather than the world itself therefore.

Suchness is, in other words – although this point might not, at the first hearing, seem to follow – the perception of the world ‘in flight’, or ‘in movement’, because this is how it is in itself. The world is always in flight – it’s not going anywhere we can know about (and it didn’t come from anywhere we can know about either) but it is in flight all the same. It can never not be in flight – if it did it would cease to be the world. It would become something else instead.

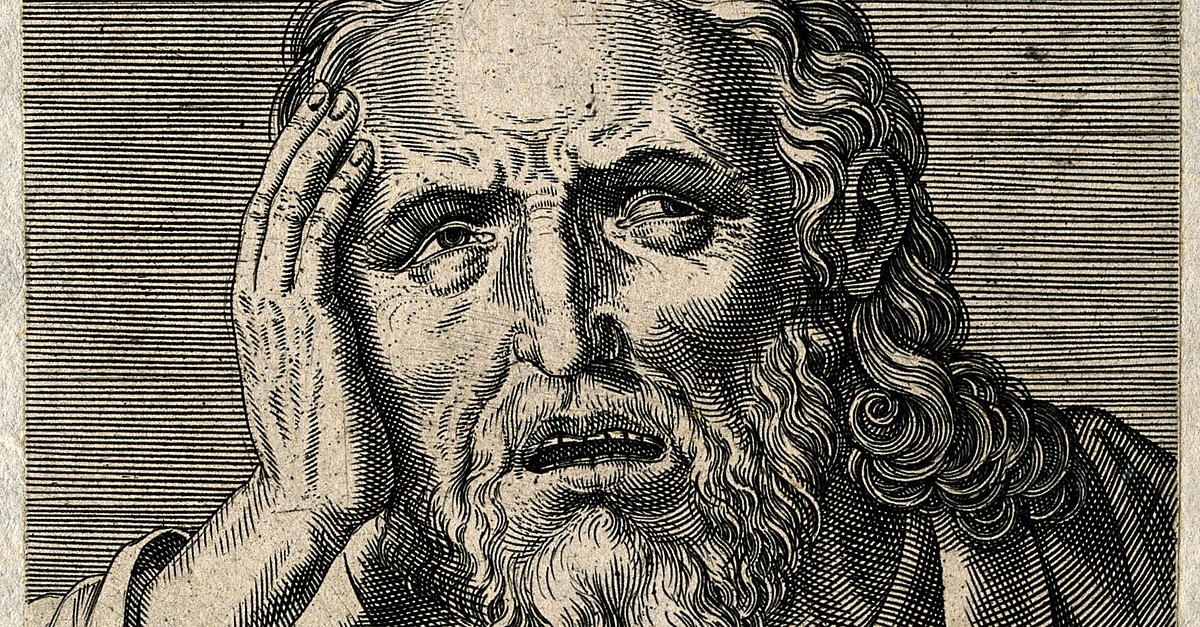

Saying that the world is always in flight is to echo what Heraclitus is telling us when he says ‘All is flux’. The world is coming from ‘we don’t know where’ and it’s on its way to ‘somewhere else that we can’t know about’, but beyond this we can say nothing. We can’t therefore relate to the world (or relate to reality) by using thought – thought only being able to say what things ‘are’. If all we can do is ‘say what things are’ then how can we relate to what is ‘in flight’? How can we relate to what is actually real? There is – after all – no such thing as ‘how things are’.

‘Things are what they are’ (we might glibly say) but what they ‘are’ is pure ungrounded motion. No static taxonomy can represent this state of affairs and – needless to say – all taxonomies are static. Nothing can represent ‘the world in flight’, none of our ideas or theories can tell us anything at all about it and – this being the case – we might wonder why we spend our entire lives in a fog of ideas, concepts, thoughts and theories; whatever it is we are concerning ourselves with, it’s certainly got nothing to do with what is actually going on!

The state of flux that Heraclitus is talking about has nothing to do with what we ordinarily understand as movement (or motion), however. Rather than talking in terms of movement from A to B (which is of course not in the least bit challenging for us to conceptualise) we could say that Heraclitian flux is where nothing ever gets to actually exist – nothing ever gets to exist because existence requires duration and there is no duration in Heraclitian flux. There is no such thing as duration at all – that is a meaningless concept, strange though this may sound to us.

Nothing has any extension in the real world, nothing has any possibility of ‘continuing as it is’ (or as we might suppose it to be) and to say this is baffling for the thinking mind is a serious understatement. The lack of extension is baffling to us as well because the thinking mind is what we use to relate to reality, or make sense of reality. Our problem is that duration (or extension) is the precondition for understanding anything whilst – actually – it isn’t a feature of reality at all, but only the (necessary) assumption of thought. It’s a kind of artificial gimmick, nothing more.

What’s to extend, after all? If we are to extend something, and give it duration, then it has to be something fixed or static in the first place. It has to be something we can locate or else there’s nothing to work with. Otherwise, there’s nothing there for us to grasp hold of and if we can’t grasp hold of something (or know what it is) we can hardly ‘extend’ it! There’s no grasping the world when it is in flight – to grasp it would be to arrest its flight and that’s the one thing we can’t ever do. That would be a contradiction in terms – there’s no grasping anything when it’s Heraclitian Flux we’re talking about.

If nothing ever sits still, not even for the merest fraction of a second, then there is no ‘purchase’. Nothing hangs around long enough to exist – the moment it comes into existence is also the moment it goes out of existence again, and so there simply is no existence. There’s nothing to grasp, nothing to hold onto and extrapolate from, but that doesn’t mean there’s nothing there – it just means that we can’t know about what’s there. ‘Something unknown is doing we don’t know what,’ says Arthur Eddington. Just because we can’t create a narrative about what’s happening doesn’t mean that there isn’t anything happening. To say that reality ‘won’t fit into our categories’ or that it ‘won’t stay still long enough for us to measure it’ isn’t saying anything against reality – the shortcoming lies with us and our clumsy way of relating to the world, not with reality. The problem is with us, nowhere else – we’re looking at things in completely the wrong way.

There’s absolutely no need to know anything about Heraclitian Flux. We might argue that it is human nature to ‘want to know’, that it is an expression of who we are to want to say something about the world we live in, but this is only superficially true. It’s only superficially true because we too are flux, we too are ‘the world in flight’ so why would flux want to seize hold of flux? And if it did seize hold of itself then it would no longer be in a state of flux but in a state of stasis and so what could possibly be gained by this? Stasis isn’t a real thing anyway, it’s a ‘mind-created abstraction’ not a reality and so there is definitely nothing to be gained as a result of this exercise. It would be like killing a butterfly and putting it in a display cabinet because we think we might learn more about it this way, or – to give a more familiar analogy – it’s like catching a songbird and incarcerating it in a cage because we love its song, only to find out that it won’t sing in captivity.

We obtain a static representation of the world by doing a kind of ‘screen-grab’ – we then forget that it is just a screen-grab and think it’s the real deal. We would get upset if anyone were to try to tell us otherwise. This is demonstrably true – if someone did come along and say to us that the world we know (and take to be the only world there is) was only a static picture or abstract view that has zero resemblance to the dynamic reality, the chances are overwhelmingly that we would not go along with this. This is something that we automatically dismiss and the reason we automatically dismiss or discount it is because we can only have the type of existence we understand ourselves to have when we do live in a static screen-grab of reality. We would have no defined or separate existence otherwise, there would only be ‘the Flux’.

There’s a principle here that – in terms of sheer elegance – far surpasses any static theory or model we might come up with, and the reason we don’t ever pay it any attention (the reason we prefer our theories and models) is simply because of the reason we have just given we don’t want to see the idea we have of ourselves knocked off its pedestal. We’ll stick with any crappy worldview rather than risk this. If we need to, we will distort reality beyond recognition in order to preserve the primacy of the reified self (and the reified universe which it fits so very snugly into). It’s not so much that ‘the net of logic’ which we cast in the attempts to snare the essence of reality is ‘clumsy’ or ‘lacking in aesthetic appeal’ but that it simply doesn’t catch anything, as Rudy Rucker says.

When ungrounded change or cosmic flux is represented in terms of a logical framework then what we are claiming to represent is actually being converted into ‘the antithetical version of what it really is’ without this in anyway being acknowledged. Our theories and concepts don’t clarify therefore, they confuse. Far from illuminating matters, our ‘explanations’ plunge us into darkness. When we insist – as we do insist – that reality can be pinned down via our mental categories in such a way that nothing important is left out, we are turning everything on its head. We are turning everything on its head because everything important IS being left out, and what’s ‘left in our net’ is infinitely trivial, infinitely superficial, infinitely petty. The main event has been forgotten about and – instead – we are giving all our attention to the hot dog stall outside the main entrance. We have missed the point entirely.

If the only way we have of relating to the world around us is by representing it to ourselves in a static way then this means that we ourselves necessarily become part of that same ‘static representation’ – it simply couldn’t work in any other way. When we become part of the static representation ourselves then this puts us in a very particular position – it puts us in the position of ‘being glitched whilst being constitutionally unable to know anything about it’. We have incurred the curse of the invisible glitch – the glitch no one can tell us about, which is the ‘glitch in meaning’ that comes about when we become part of a system that only exists because of self-referentiality. The game is only real to us when we play it, but it is real in a very particular kind of a way – the game is only real because of the one who is playing it (i.e., it is only ‘real’ only from this conditioned viewpoint) and looking at this the other way – we ourselves only seem to ourselves to be real because we have made the game real (by adopting this conditioned POV). This is self-referentiality and self-referentiality is disguised meaninglessness. There is no suchness here, there’s no genuine nuance – only continual superficial distraction. There is only the never-ending blandness which is produced in industrial quantities by the ‘Distraction Machine’.

Art: bretkelly.com