Within the remit of the game I am the absolute boss. However I want things to be, that’s the way they’re going to be! Nothing gets to happen unless I have said that it can. And yet the whole point about the game (about any game!) is that I don’t allow myself to see that I have set things up this way. The whole point of the game is that I don’t know that it is a game, that I ‘lose sight’ of the fact that it is a game. I arrange for things to be a certain way (for certain key parameters to be in place) and then I act like I didn’t arrange anything. I act that I haven’t put those key parameters in place.

What this means of course is that I am ‘in control’ in a very fundamental way. I’m never really going to lose control – not in the game, anyway. The onus is on me – if I don’t specifically say that a thing has to be there in the game then it won’t be there. The idea of control sounds good. Straightaway I like it, straightaway I warm to the idea. It appeals to me. I don’t see – therefore – that the attractive aspect of control hides a very grave limitation: everything depends upon me, every single little thing, and yet I’m not really as smart as I like to think I am. In fact, I’m not smart at all!

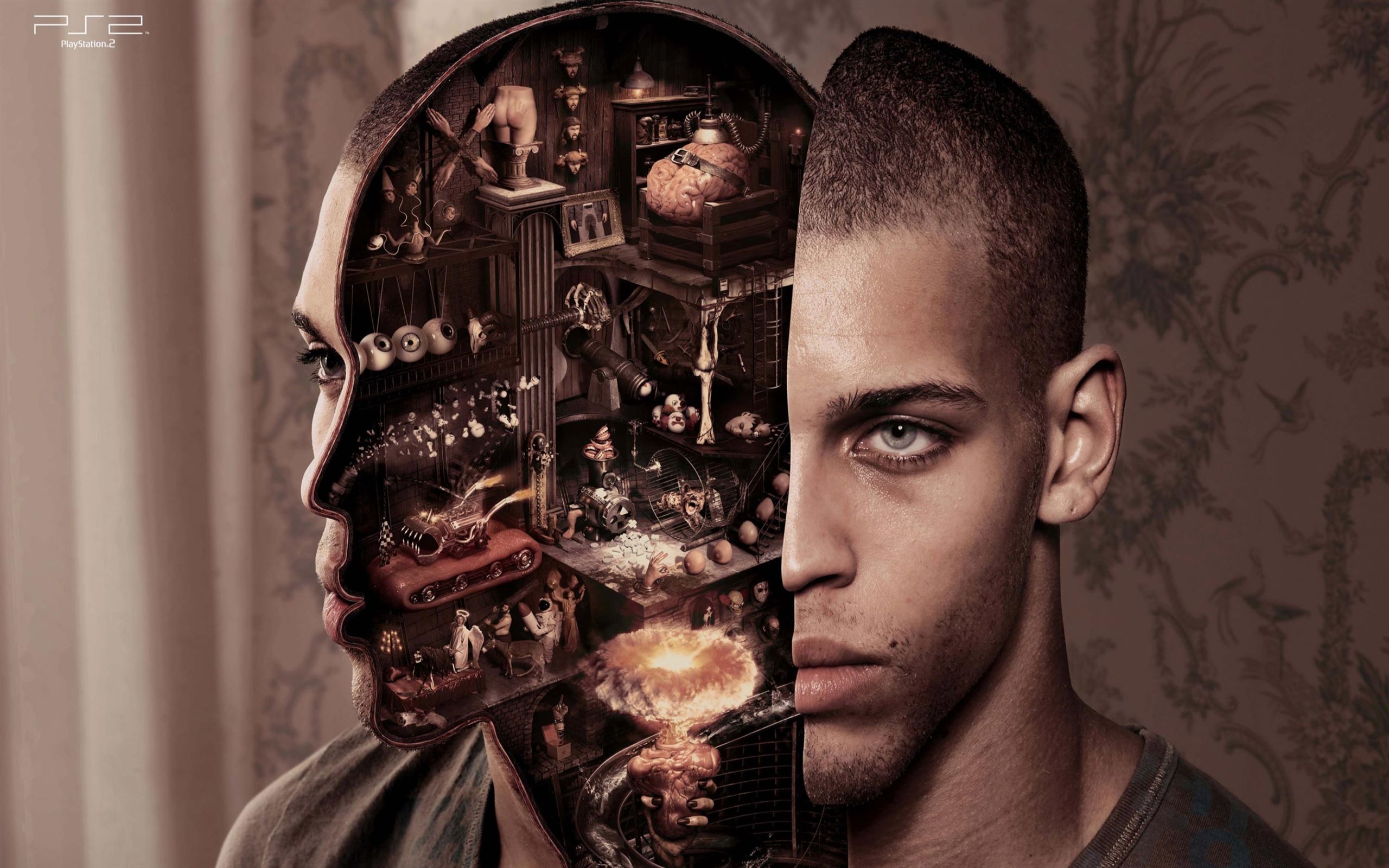

The particular game that we are concerned with here in this discussion is the game of the rational mind, and the thing about this particular game is that it allows us – it facilitates us – to feel smart no matter what! The game of the rational mind is all about being in total control; not in total control of reality but of the way in which we see reality. In other words, whatever I want to believe to be true seems (to me) to be true. Whatever I want to be true gets to be true…

This is pretty obvious once we think about it – we only need to have a good look around to see that this is the way things are. All we need to do is to check out all the people we know, all the people we might happen to meet during the day. Everyone has their own view of the world – and everyone thinks that they are right to have this view! Everybody has their own bunch of stuff that they believe to be true and the reason they believe it to be true is because they want it to be true. Every person we meet gets to be the boss within the game of their own mind. What I say is true, gets to be true; what I say isn’t true, doesn’t get to be true. I am in total control of this show!

Again, there is an immediate appeal to this idea. Wow! I get to be totally in control! I get to be the boss! Great! Only of course this initial feeling of satisfaction and security conceals a tremendous limitation, the direst, most dreadful limitation there could be. What limitation is this? The limitation of being a total, self-deluding fool, the limitation of being the gullible believer of my own lies, the limitation of being the hapless out-of-control victim of my own bullshit…

Needless to say, none of the above accords with what we have been brought up to believe about the mind. We have been brought up to believe that the rational mind is an instrument that faithfully shows reality to us, rather than being like a ‘flattering courtier’ who tells us what we want to hear. We certainly haven’t been brought up to be wary of the rational mind because of the way in which it automatically tends to distort reality for us in accordance with the way in which we (unconsciously) want it to be, in accordance with our unexamined expectations or assumptions about it. We haven’t been brought up to be aware of our ‘unconscious biasing factors’ – our conditioning.

We are also unfamiliar (and probably uncomfortable with) the idea that the rational mind is a game. This key aspect of rationality is not high-lighted for us by our educational system, which is also – if the truth were to be known – a game. What does it mean to say that something is ‘a game’? One definition is to say that a game is the closed domain of interactions that exist around (or in accordance with) a known or specified set of rules. Or we could be a bit plainer and say that a game is any situation in which all the parameters are controlled. This state of affairs is also sometimes known as a ‘formal’ system, as opposed to a ‘real world’ system where the parameters are not controlled.

In a real world system the parameters are not known and not under control and – when it comes right down to it – they don’t even necessarily have to exist at all. Parameters aren’t necessary. The most succinct definition of a game is, therefore, to say that it is a closed (or ‘defined’) system, as opposed to unmodified reality which is open (or ‘undefined’). The rational mind is then ‘an arbitrary description of a reality which is itself quintessentially indefinable’. Or if we wanted to be more rigorous, we could say that the rational mind is ‘the closed set of all possible definite statements about a reality which is itself not closed and about which no absolutely definite statements can be made’.

The rational mind is a dealer in relatively true statements about the world, not absolutely true statements, which is what we almost always take them to be. It is incapable of making absolutely true statements. A ‘relatively true’ statement – we might say – is a statement that is ‘true in relation to the frame of reference that has been assumed in order to make that statement in the first place’!

Put like this, the everyday mind doesn’t sound so infallible after all. Put like this, the unfamiliar idea of the everyday mind as a game (or a trap) doesn’t sound quite so crazy or far-fetched. Perhaps there is some sense in it. And the understanding that this never-questioned mind of ours works by producing a private bubble of virtual-reality made up of a closed set of relatively true statements that have been mistaken for being absolutely or finally true (rather than only provisionally true or ‘only true within the remit of the game’) sounds like something it might just be worth knowing.

Knowing this might help prevent us running into a whole heap of problems in our lives. We might learn to question our thoughts rather than automatically believing in them, in the manner of a sleep-walking voter somnambulistically voting for the same useless – or worse-than-useless – government term after term.

So why is it that this potentially useful understanding of the everyday mind is never taught in schools, colleges, universities or anywhere else? Surely we would be far better off in school learning about the relativity of the ‘definite world’ that our minds manufacture for us rather than learning a lot of crap about history, geography, etc, (which we could easily learn ourselves later on in life if we were interested, and enjoy it a hell of a lot more into the bargain)? Why haven’t we ever been acquainted, at the very least, with the idea that this mind of ours is a fantastically expert ‘spinner of illusions’, more expert than any politician? Instead of making us aware of illusions, our society actively sells them to us – it heaps them upon us in generous helpings from the moment we’re old enough to take notice until the moment when we’re finally ready to check out.

So why is the idea that the ‘defined world’ which our conditioned mind shows us isn’t actually the real world at all so well hidden, so conspicuously absent, in our culture? One answer that has been put forward by existential philosophers and existential psychotherapists is simply that we are afraid of freedom. Erich Fromm even wrote a book called that – “Fear of Freedom”. Freedom scares the crap out of us. It scares the living bejesus out of us and so what we do is to pretend that it isn’t there. We play a game, which is the game of ‘Let’s pretend that we don’t have the freedom to see the world in another, more expansive way’. We play the time-honoured game of ‘down-sizing’ – which is the game of “Let’s pretend that we are ‘this and nothing more’…”

So out of our unacknowledged fear – the fear we say we don’t have – we create a virtual reality bubble for ourselves, a ‘formal system,’ and we say that this formal system is ‘the whole of what is possible’. If anyone comes along and says that it isn’t then we either burn them at the stake or medicate them, depending upon what era we are talking about. And even without these more ‘extreme’ social sanctions, we very soon find out that no one will listen to us if we start saying that there is another world beyond the one we know. The wall will come down. The fences will be put up. The only people who might listen to us are cranks, hippies and new-agers and who cares about them?

If you were to tell me that there is a world beyond this one, a bigger world, a hugely more spacious world, world so vast that all the ‘fixed and definite things’ I know about and am familiar with – and which regularly seem so terribly important to me – dwindle into utter insignificance in comparison, then I don’t have to listen. I don’t have to give ideas like this the time of day. After all, I am the boss of my own mind. Amn’t I?