Unacknowledged pain – or fear – drives us out of ourselves. We don’t know that we have been driven out of ourselves – we carry on regardless, not realizing what has happened, not realizing the fate that has befallen us, which is the fate of not really living life at all but somehow thinking that we are.

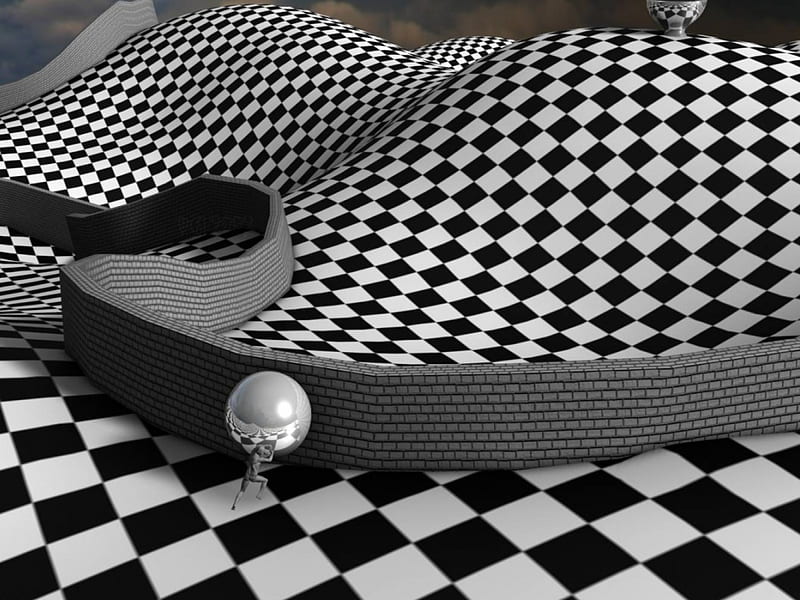

It is as if I am living in a splendid mansion, but bit by bit I am losing access to all the rooms. I am being moved out, barred, exiled from my own rightful domain. Eventually I am pushed out into some small outlying room, having to make do with this cramped and cluttered space for my living quarters. And later on maybe even this limited space is denied me, and I have to move into the broom cupboard. Or maybe I have to move out of the mansion entirely and take up residence in a dilapidated, wood-louse infested garden shed…

The thing is that when we lose space like this we don’t know what it is that we have lost. When we are compelled to live outside of ourselves, we don’t know that we are living outside ourselves. Or to put this another way, when we are not at home in ourselves, we don’t know that we aren’t at home in ourselves.

This is a version of what Robert de Ropp calls ‘the myth of the mad king’. The myth in question is that of the king who has left his throne and his palace and lives in a stinking cellar instead, wrapped in soiled rags, sitting on a packing case and holding an old stick in his hand, thinking the whole time that he is still on his throne, wearing the richest of garments, clasping his jewelled sceptre – the symbol of his exalted office – in his hand. He has sunken as low as he can – having ended up in the cellars – but still cannot be dissuaded from believing that his situation is the same as it always was, that nothing at all has changed. He refuses to take any notice of what his concerned courtiers are telling him about his situation.

And yet although we don’t have any sense of what has happened to us – that we have been pushed out of our rightful dwelling place – we do suffer from the consequences. The most visible consequence is deep-rooted insecurity, i.e. we don’t feel at all sure of ourselves. We are unsure of ourselves on a very deep level, but rather than seeing this insecurity clearly – which would make our situation clear to us – we compensate for this insecurity and as a result of the various compensatory mechanisms we experience only the ‘surrogate versions’ (or ‘analogues’) of the pain that arises from this debilitating lack of sureness about who we are.

This compensated pain is not immediately perceptible as pain – in the first instance, it will tend to manifest as a sense of satisfaction in some external arena. So for example as a result of compensating for my latent insecurity I might say that I am this or I am that, and I will put a lot of force and energy into positively asserting who I am. This type of pain-displacement, this type of uncompromising positive assertion, is generally known as ‘ego’! Having created a positively-asserted identity for myself I will initially experience a strong sense of satisfaction about it. I will feel good about this situation and a familiar term that is used to refer to the good feeling that I have about the definite identity that I have created for myself is pride. I go around feeling ‘full of myself’, feeling cockily ‘sure of myself’, but really it is not my ‘deep-down self’ that I am sure of but only the superficial one that I have – out of necessity – manufactured for myself!

Another manifestation of existential insecurity is when I go around asserting very strongly that this is the case, or that that is the case. I make a habit of strongly asserting what is true and what is not true. I have opinions, in other words. My opinions might be based on nothing more substantial than my own inane prejudices but all the same because they are so certain they serve to bolster up my sense of myself – the unconscious logic is that because my opinions are so definite, then so too must the person who has them. The logic is that because I am strong in my opinions (and have lots of them – one for every occasion!) I must also be strong in my identity. By adopting numerous firm ideas about things in general, I also gain a firm idea about the one who has these ideas. Everything gets painted with the same brush – the brush of certainty. The fact that I have rendered myself incapable of questioning (or critically examining) my own opinions means that I am also incapable of questioning myself; my dogmatic view of the world is immune to interrogation and thus so am I!

My firm opinions about this, that and the other are of course only the most visible or easily accessible manifestations of my underlying belief-system and so the point is that the way in which the ‘made-up self’ creates a fixed and unquestionable view of the world for itself is also the way in which it creates a fixed and unquestionable view of itself. The rigidity, the intractability, the utter opacity of my belief-system is therefore a ‘form’ of strength – it is a display of strength on the outside which serves to effectively distract attention from the lack of strength which I feel on the inside. So we can say that the more certain I am about things, the more dogmatically sure about things I am, then the more this demonstrates my complete lack of certainty on the inside. Everything is invested in a hard, and therefore dangerously brittle, ‘outer shell’ of belief – an outer shell of unexamined ideas and prejudices that I simply cannot afford ever to look into…

One key way in which inner insecurity manifests is in fixed or unquestionable belief-structures, and the other is in the over-valuing of goals. When I over-value my own goals (or the goals that have been placed in my head by anyone else, for that matter) then this becomes a form of sickness. It is readily apparent that this is a sickness because of the way in which life itself will start to drain out of me – I remove myself from life with my over-valued goals, I enter into some kind of dreadfully boring private game with myself (or with other people who have chosen to play this same game). What happens as a result of this withdrawal from life is that I become very serious and dry in myself, automatically assuming that the only things that matter are those things which have a direct relevance with my goals, and how I am to obtain them. This being the case, I am now no better than a creaking old robot, a mere mechanism!

Another variation of this theme is that instead of becoming tediously dry and pedantic like a fusty hide-bound old scholar or a fussy, humourless rule-obsessed bureaucrat, I become fanatical. I become very serious, very driven, very intense about my goals and I don’t mind what damage I do in the pursuit of them. All my time and energy goes into whatever cause it is that I have adopted and the not-very-well-hidden benefit to this unreflective zealotry is of course that I never have to look at my own life and what the hell I’m doing with it. And the fact that I am so keen to avail of this benefit, this ‘secondary gain’, proclaims very clearly (as if it were shouted from the roof-tops!) that what I don’t want to examine won’t stand being examined. My basis is infinitely shaky – my insistence on saying that my goals matter so very much proves that they don’t really matter at all. What I value is not the cause which I make such a big song and dance about, what I value is the ability of this cause to distract me from ever seeing the truth…

The general process which this illustrates is essentially one in which inner uncertainty is transformed into outer certainty. The uncertainty doesn’t work for us and so rather than hanging out here – if we have any say in the matter at all – we spend our time in the outer zone of manufactured certainty. We live our lives, as best we can, within this restricted domain of definite viewpoints, and specified (or prescribed) behaviours, and we write off any experience of the inherent uncertainty of things as being something pathological, something unwanted and potentially dangerous. This is what lies at the root of the deep-rooted human tendency to fear change and cherish fixed patterns – the ubiquitous human tendency known as conservatism.

External certainty seems to work for a while, but then it inevitably backfires on us. When we say that where we are is the RIGHT place this may make us feel better in a superficial kind of a way, but it also causes us feel worse on a deeper level and so we can say that what happens as a result of ‘validating our position’ is that we become subject to the form of secondary or displaced pain known as neurotic suffering. Neurosis is what we put ourselves in line for as a result as embracing ‘external certainty’, as a result of embarking down the road of unreflective conservatism. Saying this tends to sound a bit strange since an unshakeable firmness of purpose and outlook sounds strong to us, and not at all ‘neurotic’. Any impression of genuine strength is however only superficial since as we have said, all this certainty, all this firmness (or rigidity) of belief and purpose, is founded upon nothing more than the fear-driven need for security, which is of course the furthest thing from strength that one could possibly imagine!

Our whole assumed identity is just a shell, when it comes down to it, and it is the inherent brittleness and fragility of this shell that gives rise to the signs and symptoms of what we call ‘neurosis’, or ‘neurotic mental illness’. When my sense of myself is based on an identity which is essentially a brittle shell then it is inevitable that all of my energy and attention is going to go into the thankless task of protecting and securing this ego or identity. I am therefore going to spend all my time being anxious or phobic or obsessive or angry or jealous or envious or defensive or paranoid or irritable or cagey or generally reactive in some way or other. All of my time is going to be taken up with this crappy business and as a result I’m not going to have much of a life. I’m certainly not going to feel very happy in myself – I’m not going to spend much time feeling peaceful or feeling in any way connected to the people around me, or to the world as a whole. On the contrary – I am going to be perennially isolated and miserable.

Neurosis means that I am engaged on a fulltime basis trying to maintain (or make viable) something that is never, ever going to get anywhere. In short, I am investing everything in what is – by any standards – a complete ‘non-starter’, a complete ‘no-hoper’, and it is this ‘bad investment’ which is the source of all my subsequent suffering. This – needless to say – is very far from how I see it – I see my suffering as being due to the fact that the world is not providing the right conditions for me, the conditions in which I would thrive. The idea that I will be happy when the right conditions are provided (when everything is the way I think it ought to be) is something that I simply never doubt.

Having said all this however, it is the case that we can get a certain amount of mileage out of the high-maintenance brittle shell which is the conditioned identity: we have to dedicate almost all of our attention to matters which are of interest to it (and which are – on this account – utterly trivial) and are therefore trapped within a very narrow and repetitive modality of awareness, but by and large we get by without any major crises. It seems that most of us get by in life without ever having to really confront the highly unsatisfactory nature of this type of restricted existence, without ever being made truly aware of just how short a leash it is that we are kept on. The overriding question in life is – we might say – the question of whether we feel truly feel the pinch (or squeeze) of conditioned existence or whether we carry on (in some kind of a fashion) without ever really being made directly aware of it.

On the whole, however, it is the case that the phoney and profoundly limited sense identity which we have adopted becomes more and more unsatisfactory, more and more demanding upon us, as time goes on – permitting us progressively less freedom, less and less access to our true nature, as we get older. We become ever more constrained to be exclusively concerning ourselves with what we could call ‘security issues’ – the security in question pertaining of course to the conditioned self.

This might mean on the one hand that we end up complaining and whinging and moaning or angry an awful lot because the deal we receive in life doesn’t match what we expect or think we deserve, or it could mean that we get anxious the whole time because we feel that some catastrophic outcome is waiting around the corner. In some way or other we become ‘jaded’ in our outlook. Whichever way it works, we become more and more absorbed ‘in ourselves’ and as a result less and less connected to the wider world – the world which is not made up of ourselves and our crappy issues.

The point here though is that it isn’t really ourselves that we are caught up in but the conditioned identity! What is happening in neurosis is that the conditioned identity’s existential crisis is made into our crisis, and so we are having to suffer on its behalf. This is what neurotic suffering is all about – consciousness is made to suffer on behalf of the self-image, which is absolutely bound to suffer since its nature is quintessentially narrow, rigid and inflexible. The self-image may apparently function well for a while – and everything may seem to be rosy, in the manner of some mythical golden age – but it is only a matter of time before the cracks start to show, before it all starts to get a bit creaky, before things start to wear just a little bit too thin…

Just to review what we have been saying so far – one of the first things that tends to happen when the conditioned identity starts to go seriously downhill on its inevitable path to rack-and-ruin is that there is a general over-valuing of goals and purposeful behaviour, which translates into a way of life where it is very important to be busy all the time, doing this and doing that, going here or going there, chasing this goal or chasing that. As long as we’re being industrious from morning to night then we’re validated – we must be OK in this case because we’re ‘doing stuff’. Or it could be that the compensatory mechanism leads to an unhealthy perfectionistic emphasis on ‘getting things right’, or maybe to an obsessive interest in winning, in being the one who gets validated, who gets proven to be right or superior in some way. Everything then becomes about being ‘the best’ – which in our ridiculously shallow, goal-orientated culture actually gets to be seen as a good thing! In this climate everyone competes with each other to see ‘who is the best’, so that we can stand at least a chance of temporarily assuaging the repressed feeling of inferiority that we are permanently saddled with. We can then legitimately donate those unwanted feelings to the losers!

Another tried-and-trusted compensatory mechanism is that I might get prejudiced or judgemental in my outlook, which means that I see my particular of seeing the world as being self-evidently right, and everyone else’s as being self-evidently wrong. All of the repressed pain and insecurity that I am feeling thus gets turned into judgementalism directed towards other groups, who I can complain about and vilify. This tendency leads me to the point at which I become utterly incapable of tolerating any dissenting views on anything – I might perhaps join some sort of extremist group, I might become an extreme right-winger or fascist or I might sign up with some fundamentalist religion and become a zealot. Or I might just buckle down become a good, old-fashioned conservative – which is the basic way of obtaining some sense of security about the fact that one is ‘right’ in one’s views, and all other (non-conservative) people are not. In this case I become rabidly neophobic and I put all my energy into staunchly upholding traditional values. Hanging on grimly to the old ways, I resist change and new ideas to the limit of my ability. I glorify what I already know (which is really nothing at all) and demonize everything else, and this unpleasant behavioural strategy is only really a more visible or obvious example of what the conditioned self always does all the time, anyway!

The extreme end-point of over-valued purposeful behaviour – the point at which we can clearly see that it is stretched too far and is teetering over a precipice – might be said to be obsessive compulsive disorder, which is where we are constantly trying to ward of impending disaster by our infinitely reiterated empty (or futile) behaviour patterns. But the disaster we are trying to avoid continues to haunt us every step of the way, which is why we are locked into the infinite repetition scenario. What this tells us is that the problem is not really our inability to successfully ward the disaster off, but that we can’t bring ourselves to admit that it has already happened. The outcome we are fighting against (which is the loss of who we really are) has already happened, but we just can’t bring ourselves to accept this…

Another, more commonly encountered end-point of the ‘neurotic spectrum’ is the form of entirely futile but intensely reiterated mental activity (or ‘doing’) known as anxiety. Anxiety is usually seen as the unaccountable illusion that we can’t perform when the truth is that we can, when by rights we really ought to be able to. We doubt our ability to successfully execute the type of goal-orientated behaviour that normally – under non-anxious circumstances – we wouldn’t think twice about. Anxiety is conceptualized as an acute form of ‘unwarranted self-doubt’, in other words. From the perspective we are putting forward here however it is not the semi-repressed conviction that we are not able to carry out the goal-orientated behaviour that is a delusion but the self we think we are. The illusion is nothing other than the self which we think ought to be able to successfully execute the purposeful action. It’s not the ‘doing’ that’s the problem, in other words, but the ‘being’.

The over-valued purposeful behaviour was – after all – only there to compensate for the repressed perception that there is no one there doing it, no one there behind it, and so when the purposeful behaviour starts to feel less solid, less reliable to me, then this is the beginning of insight and not a ‘delusion’ at all. This how I start to see that there is something amiss with the whole set-up, something dodgy about it, something phoney about it. Anxiety equals ‘displaced insight’, we might therefore say. Eventually, the devastating sense of doubt that I am experiencing with regard to my capability to effectively do will run its course and turn from being doubt in my ability to do, to doubt in my ability to be, and at this point the insight into the true nature of my situation will be complete rather partial. Or to put this another way, I will be experiencing the doubt where it belongs (in the being department) rather than where it doesn’t belong (in the doing department)…

In anxiety everything is a strain, everything is so much harder than it should be, and this effort manifests itself in form of tension both mental and physical. What we are really trying to do however is not to ‘cope’, or solve problems, or deal with all the nitty-gritty trials and tribulations of everyday life (which is what we think are trying to do); what we are really trying to do is to be someone (or something) we aren’t! We are trying to maintain an identity which doesn’t belong to us, and which never could belong to us. No matter how hard we try we can’t ‘be’ this person, this being, this identity and this – because we are so set on playing the game – manifests as an absolute crisis for us. Every last bit of our energy is going into the struggle: we are willing ourselves along the way, step by gruelling step. We are trying to the very limit of our ability to ‘make it happen’, but it isn’t going to happen and deep down we know that it isn’t.

So if we look at it superficially we say “I can’t do what I’m supposed to do” and this is called anxiety, but if we look more deeply into the matter we can see that the problem is that “I can’t be who I’m supposed to be”! Anxiety’s just the symptom, the underlying problem is – as Alan Watts says – one of ‘mistaken identity’. This is a kind of obvious thing really – if I am eaten away by a painful sense of self-doubt, by a crippling lack of belief in myself or my abilities then it makes sense that this could be because there isn’t any real self there, because there isn’t any genuine source of strength or authority, only a precarious inauthentic shell-personality.

Clearly, the biggest disability or handicap it is possible to have is the lack of a connection of who we really are! Without this connection we simply have to forge on ahead through the difficulties of life on the basis of a flimsy fiction, on the basis of some make-shift make-believe fabricated identity. As we have said, this can work for a while, or for a certain amount of the time, just so long as we focus hard on not looking too deeply into ‘who we think we are’. We then get buoyed along on a powerful tide of euphoria (or ‘false self-confidence’), which is exactly the same thing as the dutch courage that buoys us up when we have a good few stiff drinks to get us through a difficult situation. We all know that this sort of alcohol-fuelled confidence can’t last – either is disappears quickly due to some kind of a nasty shock, or it else it just gradually ebbs away, leaving anxiety and depression in its wake… Once the dutch courage associated with an unreflective belief in the false self starts wearing thin, it stands to reason that the world is going to start looking like a very intimidating place. The world never looks very inviting when we are dragged reluctantly from our comfort zone!

So – as is very well known to any psychotherapist – the pain of our neuroses has its roots in our desperate attempt to ‘bolster up ourselves up’ in the face of existential insecurity by adopting some sort of hard exterior or personality armour. The crippling symptoms of neurosis are a very blunt message to us really – a message that we are simply not going to get anywhere on this basis, a message that no matter how hard we try to ‘wing it’ it just isn’t going to work out for us. Seeing our neurotic pain in this way would of course be very helpful to us – it would in fact be extraordinarily helpful. It is like discovering that the road you are going down doesn’t actually get anywhere, that it is a dead-end, a cul-de-sac. How much better would it be to discover this earlier in life rather than later, before too much of our life has been used up stubbornly refusing to admit to ourselves that the road doesn’t get anywhere, obstinately refusing to see that we are trying to do something that is not only impossible, but also quite pointless.

The way we generally do things however it that we are ‘stubborn to the last’; that’s the unconscious way – when we are in the unconscious mode we implicitly believe that being stubborn and inflexible is what will save us, if we persist in it enough. We believe in persisting with our folly: the more difficult things get the more we batten down the hatch, the more we we close down, the more stubbornly inflexible we get. We have after all already committed ourselves to the path of ‘denying the truth’ and so really we have no choice other than to carry on down this path to the bitter end, until we finally reach the point where we actually aren’t able to carry on any more. Only when we have no choice in the matter will we concede defeat, and even then we will do it with bad grace…

We can say therefore – just to continue with the general analogy – that the various manifestations of neurosis (which are always characterized by the motif of ‘futile activity’) are all about us trying our level best to turn a blind eye to the truth, which is becoming harder and harder to ignore all the time. As the truth of our situation becomes harder to turn a blind eye to we are obliged to escalate our pain-displacing (or ‘awareness displacing’) activities until the counterproductivity (i.e. the ‘unwanted side-effects’) associated with it reaches a point when we can walk the path of denial no further. So in neurosis we can say that what is happening to us is that the house that we have built for ourselves is disintegrating, falling to pieces all around us, and rather than see this distressing fact we distract ourselves one way or another by getting very interested and very absorbed in various pointless activities (pointless, that is, in every way except in terms of their ability to keep on distracting us). These distraction (or displacement) activities have a limited lifespan in that they work for just so long, and then they fail to work. All comfort zones let us down in the end – one way or another. In the initial phase of successful denial we experience euphoria, therefore, and then when the wheel (or the tide) turns so that what was successful now becomes unsuccessful (what worked well now fails) then at this point the euphoria turns inevitably into dysphoria. The good times turn bad.

Neurosis, then, is always made up of cycles and each cycle consists of two phases – the euphoric phase and the dysphoric phase. Moreover, we can say that each phase consist of two stages – the anticipation of success/failure, and the actual (apparent) manifestation of success/failure. Thus, in the euphoria phase we start off by being hopeful, by experiencing positive anticipation, and then this leads on to the triumphant stage, the exultant stage, the validation stage. And in the dysphoria phase the first stage is feeling somehow pessimistic, which then gives way to negative anticipation, and then finally the dreaded validation (or confirmation) of this negative anticipation which is outright despair with no hope at all left in it.

The most straightforward and easy-to-spot example of such a cycle is the condition known as ‘bipolar disorder’. In bipolar disorder we build a fine house for ourselves which very quickly starts cracking up and then – despite our efforts to maintain it – tumbles down again all around us, and this building up/disintegrating cycle is repeated indefinitely. In the euphoric phase of the disturbance the sense of ‘positive identity’ we have of ourselves is over-valent, over-stated, over-emphasized. The house we build for ourselves is no normal everyday dwelling place but a lavish stately home, a grandiose palace. This ridiculously overblown, absurdly ostentatious fictional identity (in which I am more of a King or an Emperor than a normal common-place average human being) is prohibitively costly to maintain however and this is what guarantees its short lifespan. The higher we elevate ourselves the bigger the fall and so my situation lurches from one extreme to another. One moment I’m living in style, living in the lap of luxury, drinking fine teas from the most exquisite china, snacking on caviar, drinking Champaign, being waited upon hand and foot, and then next moment I’m down in the gutter, a person of absolutely no worth, having the vilest of rubbish thrown upon me, being insulted and humiliated at will, being unceremoniously urinated upon by every passing mongrel…

Bipolar affective disorder can come in relatively long cycles, spanning months, or it can manifest in very rapid cycles, occurring within the time-frame of hours or even minutes. There is a connection with anxiety here even though we might not generally see it – anxiety too occurs in cycles, it just so happens that the cycles are too rapid to notice. The euphoria phase in anxiety is when we hope, when we try to convince ourselves that we might be able to regain control of the situation. Every anxious thought starts out of this (admittedly forlorn) hope – if I didn’t entertain some kind of hope that I could solve the problem, regain control, etc, then why would I even bother to try in the first place? The way it works in anxiety is that this forlorn hope is thrown right back in my face very quickly – almost as soon as I think it – but this doesn’t stop me trying it again the next moment, and so on and so forth indefinitely. The whole thing is a rapid vibration between thinking that I might be able to succeed, to realizing almost instantaneously that I am doomed to fail. In anxiety it is of course the sense of failure of imminent failure that is predominant, but because I am still convinced on a deep level that purposeful activity is ‘the way to go’, the way to get myself out of the hole I am in, I keep on trying to get it to work.

Saying that in anxiety I have still have faith in the power or efficacy of purposeful activity is another way of saying that I still have faith in the conditioned self, the self I think I am. It is as if I am sitting in my car, repeatedly turning the ignition key, hoping desperately that the engine will catch. The engine never does properly catch (maybe because the battery is flat) but because I am not willing (yet) to accept this fact I keep on turning the key. I keep on hoping.

This brings us to the last stage of the neurotic process. Although we have said that the motif of neurosis is ‘futile activity’ in one form or another, there comes a stage when this activity finally does come to an end and this end-stage is known as depression. Initially in depression there is still a bit of activity – not physical but mental as I keep on going over the fact that this terrible thing has happened to me, and reflecting on how dreadful it is. This repetitive mental activity – which is where we brood in horror at what has befallen us – is really a vestigial (and therefore deeply futile) attempt to solve the problem – the problem that I can no longer deny.

What I am looking at in depression is the irreversible decay and disintegration of the house that I have made for myself, the dwelling place that I mistakenly think of as being my rightful home. The awareness that the ruin can’t be reversed, that the process of decay has gone too far, is the source of my great mental pain. And yet combined with this despairing sense of loss there also an awareness that my identity – the identity whose loss I am mourning – was somehow false in the first place. In depression it is common not only to hear it expressed that I am hollow or rotten or unworthy, but also that I am somehow a great fake, or phoney. It is customary in our culture to contradict the depressed person and try to get then to see that these negative beliefs are merely symptoms of the illness, and that they should not on this account be taken seriously. We are told by everyone concerned to resist these dreadful ideas. And yet the ideas we are supposed to be resisting, or denying, contain a very valuable insight – the insight that my identity really is false, really is a ‘hollow pretence’.

At first this discovery comes hand-in-hand with very great suffering because we have invested an awful lot in that identity, in that false sense of self. I have said “This is me!” – I have invested in it, and so now comes the process of dis-investing. All the euphoria I obtained throughout my life by saying that “I am this literal identity” must now be paid for in the form of dysphoria. What goes up must come down. If I build (as I have done) upon the positive statement that ‘I am this’ then what I have built must one day come crashing down around my ears.

But just as the good feeling that I have derived from this definite statement of identity is ultimately unreal, so too is the bad feeling that I obtain as a result of having this statement of identity falsified for me later on, as it inevitably will be. Both euphoria and dysphoria are ultimately illusory, which is clearly demonstrated in the fact that they always neatly cancel each other out!

And once the dysphoria has run its course, as it must do, and the period of ‘disinvestment’ has properly taken place, then our time of exile is over and we are free to see that we were only living in a broken down old shed anyway, and so nothing really has been lost after all…

Image – wallpaperaccess.com