I suffer, but just how sincere am I in my wish to free myself from suffering? Pretty stupid question, huh? Everyone wants happiness, after all. That’s pretty basic. No one wants to suffer. It sounds like a stupid question, but all the same it is easy to show that our wish to rid ourselves from unhappiness is not as sincere (or ‘unqualified’) as we might have thought. Actually, the truth is that happiness is that very last thing we want, no matter what we might say…

This point – which isn’t really as strange as it might initially seem – can be straightforwardly demonstrated by taking a look at games. A basic definition of a game is to say that it is a situation on which there are two levels of meaning – one level which we are expected to pay attention to, and the other which we are not!

The territory covered by this term is far wider than that of purely formal games such as noughts-and-crosses, dominoes, darts, tennis, etc but we can use the example of a formal game to make the point. We started off talking about sincerity and sincerity is something that we may appear to have when we are wholeheartedly playing a game – in fact we often look very sincere indeed when we’re immersed in a game. The playing of games – as everyone knows – can become a very serious business! The thing is, however, ‘sincere’ and ‘serious’ aren’t really the same at all.

Let us suppose (just for the sake of the example) that you a highly-paid professional footballer, playing for your country in the final game of the world cup. The match is into the final five minutes, the score is two all, and you suddenly have a chance to score a deciding goal. The question we need to ask therefore is this – are you sincere in your wish to score this goal, and thereby win the match? Again – this seems like a pretty stupid question. Is the Pope Catholic? Do bears crap in the woods? Was Hitler a bit of a Nazi? Etc…..

There is an unexpected twist here, though – a twist we just can’t see. Let’s say that I am trying to attain the advantage, not necessarily a goal in football, but an advantage in any sort of game. On the surface my commitment is 100% – I am deadly serious about it. However, in order to believe in the goal it is of course absolutely necessary that I believe in the game, and the way that we believe in a game – as James Carse says – is by losing sight of the fact that it is a game.

So in order to be properly serious about attaining the necessary outcome in the game I need to believe in the game, and in order to believe in the game I need to make sure that I don’t pay attention to the fact that the game is only a game! The most important thing here is that I am not aware of the game being a game – this has to come first because without it we are not getting anywhere. So my first allegiance – the thing I take most seriously – is to repress this knowledge, repress this awareness. And at the same time – of course – I can’t let myself know that this is my first priority, my number one agenda. Being aware of that would ‘give the game away’. It would ruin everything.

This however creates a duplicitous situation, a deceptive state of affairs: I think that my number one priority is to press ahead for the advantage in the game, when really this isn’t the case at all. My number one priority is and always will be to ‘not let myself know that the game is a game’, as we have just said, and so the fact that I am acting as if the most important thing is to get the advantage in the game (and ultimately win at the game) is itself only a feint designed to distract my attention away from being aware that the game isn’t really important at all.

This is the way things are in all games – no matter how important ‘trying to win’ might seem to us, that isn’t the important thing at all really. The ‘important thing’ has got to be not seeing that the game is only a game. This is the actual mechanics of the thing – this is the way the game gets to work for us as a game. The really serious thing is for me to distract my attention away from seeing that what I am doing isn’t actually serious at all in the bigger scheme of things. I can’t however let myself see that this is the ‘really serious thing’ and so all the seriousness I feel about the ‘hidden agenda’ gets displaced neatly onto the ‘overt agenda’.

This way, when I experience this great sense of pressure, this great sense of urgency, I think that it actually belongs to thing I am trying to do. I am seeing the pressure ‘in the wrong place’ therefore. I am experiencing it where it doesn’t belong…

Coming back now to the example of our footballer who is about to score the all-important goal, we can say that it is of course obvious that if you are in that position you will be experiencing tremendous pressure – you are going to feel that it is absolutely important that you get that ball in the net! What could be more important to you at this precise point in time? And yet the whole point of our argument here is that it isn’t the most important thing at all. It can’t be. The ‘most important thing’ (the ultimate agenda) is for you to effectively distract your attention from the awareness that the game you’re playing is only a game.

What this demonstrates is that there is a basic insincerity going on here – as there is in all games – the ‘insincerity’ in question derives from the fact that ‘the right hand cannot be allowed to know what the left hand is doing’. The point we’re making is that there cannot ever be such a thing as ‘sincerity within a game’. The whole thing about a game is that we’re not really sincere – that’s what makes it a game, after all. What makes a game a game is the fact that we’re concealing our true motivation in what we doing! How can I be in a situation where I am concealing my own true motivation from myself, and yet be sincere at the same time?

Obviously, any claim I might make that I can be ‘sincere’ in a game is pure nonsense. That claim is itself just ‘part of the game’. The claim of ‘being sincere’ is actually a necessary part of the game since the integrity of game relies on us pretending very seriously that we actually do ‘mean it’.

We have said that games can be defined by saying that they always have two levels of meaning:

[1] The overt level. This is the level we all agree on. Here everything is obvious and above-board and everyone can see that the effort I am making is purely for the reason of attaining my goal. What else would I be doing it?

[2] The covert level. This is the level we all agree not to look at. In order to go on seeing what I’m doing as ‘important’ rather than ‘entirely arbitrary’ I have to maintain the viewpoint that I am committed to; this however has to be a secret motivation because if I knew that I have to manipulate things in order to make my game seem meaningful to me then it would no longer seem meaningful.

This means of course that genuine sincerity (or honesty) would violate the terms of the game since with sincerity there can be no such thing as a split-motivation – one level of which is overt and the other covert. Sincerity (or honesty) has to be surrendered in order to play a game. That loss – we might say – is the price we have to pay.

To play a game is to agree not to care ‘how things really are’ and care only about how we are pretending they are. To play a game is to care only about things appear, not what they really are!

This is more or less OK in the case of formal games (which is to say, games that we formally understand to be games). We may not want to hear it when we’re actually engaged in the game, but we’re hardly going to deny that a game is only a game when we’re not playing it!

Where things get difficult are in all the games that we play that we don’t understand to be games – and this as we have said is a far bigger territory than we might have thought! Eric Berne makes the point that most social interaction comes down to games of one sort of the other – ‘insincerities’, we might say, that we get involved with so habitually that we don’t see them as such. Our ‘social personas’ are games, when it comes right down to it – after all, if my persona is an identity of some sort or another that I am assuming in order to fit into a social structure, into a social system, then of course it is a game. The only time I’m not playing a game is when I am being totally honest, and how often is this going to happen?

But even this is just scratching the surface. Behind the social game there is another level of game-playing entirely, a hitherto unsuspected level – the game-playing of the rational mind!

Rationality – though we almost certainly don’t see it this way – is a game. It has to be a game because when we decide to make some sort of a statement about reality we don’t really have to make that statement, we could make some other statement, some other positive assertion, instead. This is a restatement of James Carse’s principle of freedom –

It is an invariable principle of all play, finite and infinite, that whoever plays, plays freely.

The way thinking works is simple – it starts off from ‘freedom’ and ends up with ‘the lack of freedom’! It starts off from ‘the wide open situation’, and ends up in a closed one! We pick one way of looking at things out of the pot, we pick one perspective out of many other possible ones, and then we stick with it – we pretend that this is the only possible way of seeing things, the only possible perspective. Having done this, we carry on from this basis, to see where we get to. The one thing we never do is look back and ask ourselves what the world might look like if we’d started off from a different basis, or perhaps even no basis at all….

Thinking creates a fixed picture of a reality that is itself not fixed, and this means that thinking (or the ‘thought-created world’) is a game. Another, more familiar way of putting this is to say that thoughts are abstractions, which is to say, out of an irreducible plurality of perspectives we pull out one particular perspective and then proceed to scrupulously exclude any information that doesn’t agree with the one we picked. This is comes down to exactly the same thing – a game is an abstraction and an abstraction is a game.

So my way of understanding the world, my picture or concept of what the world is, is a game. My take on reality is a game. It has to be. How could it not be if we think we actually ‘know’ it? How can we know it if (as the mystics have always told us) reality is quintessentially unknowable?

If I think I understand reality then what it is that I am understanding is my own construct of reality. If I think that I know about the world then the world that I think I know about must be my own game, the game that I am playing but pretending not to play…

This is where we come back to the question of happiness, and the desire for happiness. I can only really be happy if I am honest, if I am sincere. No one would suggest that happiness is possible otherwise! How could I be insincere and yet at the same time genuinely happy? So what this means is that I can only be happy if I let go of my mind, which is to say, if I stop believing in the static picture of reality that my mind has made for me. [We could also say that I can only be happy if I drop out of the social game, if I give up the social act, the social pretence!]

But do I really want to do this? Is this what I sincerely want?

Straightaway we can see that there is a problem here. There is a problem here since – as we have already said – there is no way to be sincere within a game. Since I don’t know that I am playing a game, this means that I don’t know that I am not being sincere, and so I am caught in a trap.

Because my ultimate allegiance – when I am playing the game – is to ‘not let myself know that I am playing the game’ – and happiness, as we have said, is only possible outside of the game, there is a particularly nasty double-bind going on. Really, what I want is to ‘go on playing the game no matter what’ but since I can’t admit this to myself what I have to do instead is pretend to myself that I genuinely want to be happy, pretend to myself that I am genuinely looking for happiness…

What I do therefore is to try my hardest to find happiness within the terms of the game. I look for happiness there, and what looking for happiness within the terms of the game means is forever trying to win at the game!

The substitute for happiness in the terms of the game is this thing called winning, and so all I can do is to keep on trying as hard as I can to win, keep on trying as hard as I can to be ‘a winner and not a loser’. This is a frustrating business because I just keep going around and around on the wheel.

I win and so I feel momentarily good, and then the wheel goes around and I have to give up what I thought I had gained, and this makes me feel bad. Winning is always cancelled out later on by losing, and feeling good is always cancelled out later on by feeling bad. Everything always goes right back to ‘zero’ and I always have to keep on starting over. Thinking that you have gained something and then losing it and then having to start over is the name of the game!

Happiness is actually the last thing I want because in order to be happy I would have to stop being who I think I am and it is ‘who I think I am’ that wants to be happy…

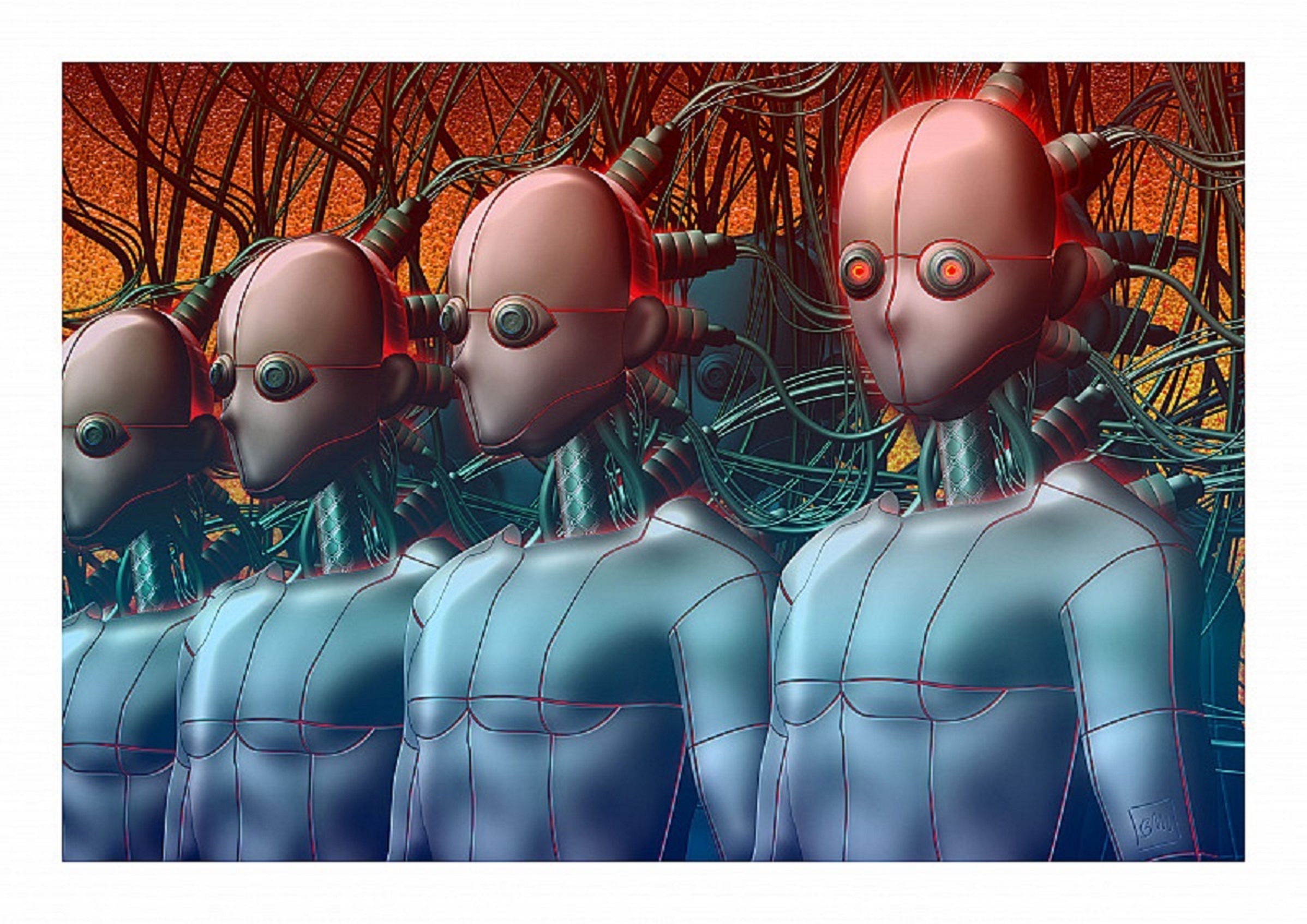

Image – mrpilgrim.co.uk