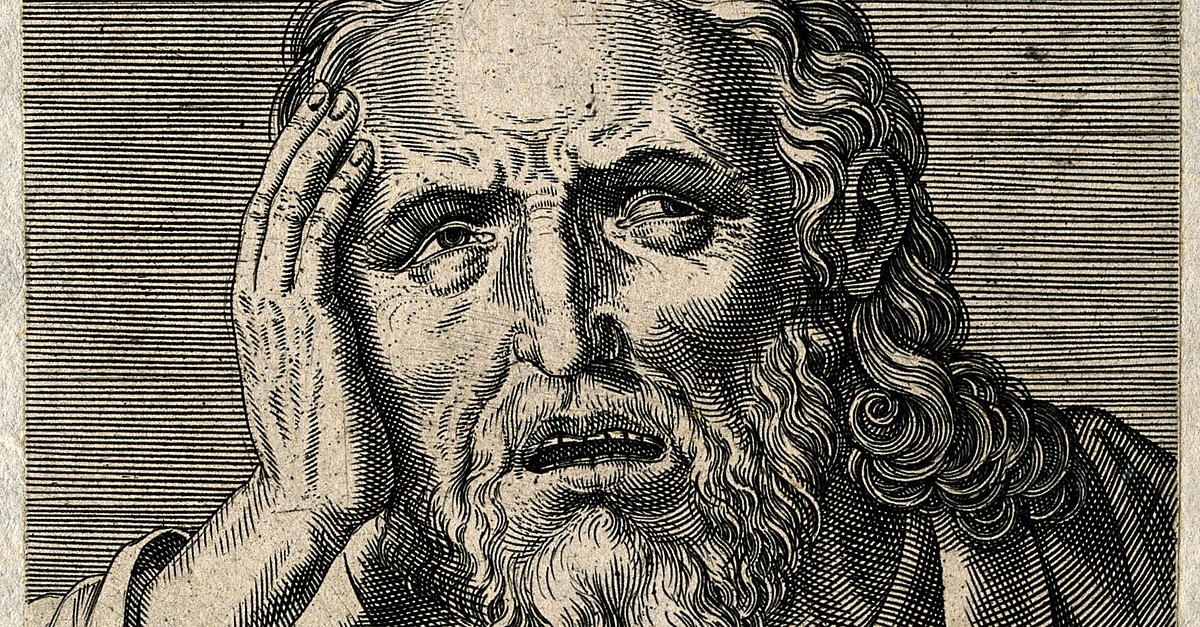

To be thinking and yet at the same time not know that we are thinking automatically separates us from reality without us knowing that we have been thus separated. We become deluded without knowing that we have become deluded. Or to put this another way, to be thinking and yet at the same time to not know that we are thinking automatically creates a false sense of self which we are then compelled to identify with. As Heraclitus said two and a half thousand years ago, “Thinking is a sacred disease and sight is deceptive.”

The implication of Heraclitus’s somewhat cryptic statement (if we can take anything from it at all) is that thinking is a far more dangerous business than we would ordinarily recognize! It is deadlier than quicksand – all the more deadly because we are so very blasé about this habit we have of thinking all the time, all the more deadly because of the careless way which we have of forever thinking without knowing that we are thinking. Even if we did accept that there was some kind of a danger involved with thinking (in terms of us immediately becoming hopelessly deluded about reality and ourselves) we would almost certainly imagine ourselves to be immune to it – we would imagine ourselves immune to it because we take it for granted that we pretty much always do know when we are thinking. It doesn’t at all seem to us that we do go around ‘thinking without knowing that we are thinking’.

This however is precisely what we do almost always do – we go around thinking without realizing that we are thinking on a regular basis, on a permanent basis. We might think that we always know when we are thinking, but we don’t! To know that we are thinking is to know that our thoughts are profoundly and immaculately empty, and how often do we get to know that? How common or familiar an awareness is that? How often do we go around seeing that our thoughts are profoundly and immaculately empty?

To say that our thoughts are profoundly and immaculately empty means simply that there’s nothing in them. And yet we always do perceive our thoughts to have something in them. We perceive it to be the case that they very much do ‘have something in them’. This is the key assumption that we make about our thoughts, and keep on making. This is why we keep reacting to them in the way that we do. This is why we keep on thinking. This is why we keep on being interested in our day-to-day ten-a-penny thoughts in the way that we are interested in them…

We invariably imagine that our thoughts have some sort of relationship with reality, some sort of genuine relevance (or correspondence) to reality, and they don’t. Our thoughts have no relationship, no relevance, no correspondence, no connection with reality whatsoever and this is why they can be said to be ‘empty’. When we clearly see this to be so, then this is when we are ‘thinking and yet at the same time knowing that we are thinking’. When we clearly see our thoughts to be empty then we don’t automatically get separated from reality without knowing that we have been separated. When we clearly see our thoughts to be empty then we aren’t compulsively driven to identify with a false sense of self. Otherwise, this is what happens all the time…

Seeing our thoughts to be profoundly and immaculately empty is therefore a pretty big deal. It is also something that practically never happens. No one ever talks about it, no one ever mentions it in discussion. It’s not the sort of thing that gets written about – not even in books on psychology or philosophy. This is a very alien type of awareness for our culture! Because this is such a profoundly alien awareness for us we are always separated from reality without knowing that we are separated from it, just as we are permanently compelled – without ever realizing it – to identify with a false sense of self. That is our lot in life – even though we don’t realize it! We think that we’re very much in reality. We think that we very much ‘are who we think we are’. We don’t just think this – we’re totally convinced of it! We couldn’t be more convinced. Dynamite couldn’t shift this conviction. Twenty years of therapy couldn’t shift it.

So the degree to which we can see that our thoughts have nothing to do with reality is the degree to which we can see ourselves to be thinking when we are thinking. This is an extraordinary statement, however. Why ever would we be taken up with thoughts, involved with thoughts, consumed with thoughts, if they have nothing at all to do with reality? Why would we concern ourselves so much with ‘unreality’? Why would we bother with it? Why would we go to the trouble of feeling good about it, feeling bad about it, feeling any sort of a way about it?

We could also say – in an equivalent sort of a statement – that the degree to which we can clearly see that our thoughts are not true (and never have been true, never could be true) is the degree to which we are actually aware that we are thinking when we are thinking. If we don’t clearly see that our thinking is ‘never true’ then as we have been saying what this means is that we get immediately translated into a realm of delusion which we have no capacity to see as such. This means that we are going to be operating very humourlessly on the basis of being this mind-created ‘delusory self’ which we are flatly (or humourlessly, in a machine-like way) incapable of seeing as such.

Whichever way we put it, it’s still going to be extremely hard for an assertion like this to be in any way meaningful for us. The assertion that all our thoughts about reality are actually unrelated to the reality to which they are supposed to be referring (the assertion that every thought we ever had is completely untrue) does not any sense at all with us. It doesn’t resonate. Who are you ever going to meet who will nod at you when you say this and smile at the self-evident truth in your words? Who would you ever happen to come across who would happily assent to the suggestion that all of our thoughts are (of course!) profoundly and immaculately empty? This kind of a view is entirely at odds with everything we believe in – it goes against our most basic assumptions regarding the nature of reality. Our basic assumptions about reality being that our thoughts can tells us something about it, that our thoughts can be relied upon to relate us to it. Our basic assumption is that our thoughts have actual substantial content.

This cherished assumption regarding the relevance or validity of our thinking is however utterly ridiculous. It is laughably ridiculous – it is ridiculously ridiculous! The point is not particularly hard to argue. For a start, we can say that all thoughts are by their very nature literal. All thoughts are by their very nature literal because of the way they can only ever agree or disagree with some sort of a definite proposition. Thoughts are always closed, in other words (just as logic is always closed). Either the cat is in its basket or it is not. Either a particular statement is true or it is not true. Either the datum under consideration can be validated by our evaluative criteria (by our mental categories) or it cannot. Either a datum fits into a category or it doesn’t. Because the thinking process always comes down, at root, to a collection of mental categories it must also always come down to a collections of YES’s and NO’s. Thought is a binary language, in other words. It’s digital. It is constructed out of what are essentially ‘black and white’ terms.

The understanding of the black-and-white (or ‘digital’) nature of thinking is the crux of everything. Our means of describing (or representing) reality to ourselves is black-and-white, but is reality? Is reality digital? Now on the face of things it does indeed seem to be the case that reality is pretty ‘black-and-white’, and that on this account it lends itself very well to our categorical ‘either/or’ thinking. There are numerous different ‘things’ in the phenomenal world and these things seem to correspond very closely (if not exactly) to our concepts of them. The world seems to be made of lots of boundaries, in other words, and boundaries are all about YES’s and NO’s. That’s what a boundary is – a boundary made up of a YES on one side and a NO on the other. If it wasn’t the case that there was a firm YES on one side and an equally firm NO on the other then there would be no hard-and-fast boundaries; there would only be uncertainty and uncertainty is permeable. Naturally uncertainty is permeable – since when did MAYBE keep anyone out? Since when did MAYBE ever bar the door effectively? MAYBE isn’t a boundary, isn’t a rule.

The world has the property therefore of appearing to be essentially composed of hard-and-fast boundaries, of ‘black-and-white’ facts (of rules) but it is also true that the world – when we look at it clearly – reveals itself to be radically deceptive as far as its surface-level appearance goes. “Nature loves to hide” says Heraclitus. So what is it that’s being hidden, we might want to know (if we have any curiosity in us at all)? What is the nature of this radical deception that we are being subjected to? What is it that nature making it so extraordinarily hard for us to see? In the simplest terms – we could say – what is being hidden from our sight is the way in which the world is actually ‘boundary-less’ and entirely devoid or lacking – therefore – in any possibility of deriving any reassuring black-and-white facts about it. In Ken Wilber’s words,

There are no boundaries in the universe. Boundaries are illusions, products not of reality but of the way we map and edit reality. And while it is fine to map out the territory, it is fatal to confuse the two.

What we’re presented with by nature is ‘apparent plurality’, and what underlies this apparent plurality – even though we can’t see it – is undivided Wholeness. It’s not a profusion of many things, it’s the One Thing spoken of by the alchemists. This ‘One Thing’ is spoken of here by Matthew Moncrieff Pattison Muir in his book on the story of alchemy:

The alchemists went a step further in their classification of things. They asserted that there is One Thing present in all things; that everything is a vehicle for the more or less perfect exhibition of the properties of the One Thing, that there is a Primal Element common to all substances. The final aim of alchemy was to obtain the One Thing, the Primal Element, the Soul of all Things, so purified, not only from specific substances, but also from all admixture of the four Elements and the three Principles, so as to make possible the accomplishment of any transmutation by the use of it.

Not just alchemy but twentieth century physics shows a tendency to come to the same conclusion. As the celebrated father of wave mechanics, Erwin Schrodinger says:

The plurality that we perceive is only an appearance; it is not real. Vedantic philosophy… has sought to clarify it by a number of analogies, one of the most attractive being the many-faceted crystal which, while showing hundreds of little pictures of what is in reality a single existent object, does not really multiply that object…

The Undivided Wholeness that we are speaking of here is a mysterious thing, and so we can say that ‘mystery is hidden beneath the apparent lack of mystery’. There is nothing mysterious about a bunch of boundaries, a collection of categories, a collection of YES’s and NO’s, but when there are no boundaries anywhere to be found what can our mental categories tell us about what is going on then? Mental categories (and the rules they embody) are only any good to us when they can be used to describe or represent a reality which is itself essentially made up of boundaries, of ‘logical divisions’ – if this is not the case then our categories, our criteria, our descriptive rules are all quite irrelevant redundant, quite absurd. If they don’t apply to reality, after all, then what’s the point in them? If we’re not describing reality with our black-and-white categories, with our literal/logical language, then what the hell are we describing?

When we describe (or represent) the world to ourselves with our logical minds and proceed to believe this description, this representation, then we separate ourselves from reality without knowing that this has happened to us. We are also – at the same time – compelled to identify ourselves with an unreal sense of self, a delusionary sense of self, a halucinatory sense of self, a sense of self that does not exist. As a result of identifying with this ‘unreal or delusionary self’ we enter into a private world and cannot readily exit it again. We’re stuck with the delusion, and the delusionary view of the world that it gives us.

As a result of identifying with this ‘unreal or delusionary self’ we enter into a closed world, a world that exists ‘only for ourselves’ and which is not on this account real. As Heraclitus says, “The awake share a common world, but the asleep turn aside into private worlds.”