All of the neurotic conditions, without any exception, can be understood by studying the properties of formal systems and applying what we learn to the everyday rational mind. This sounds very simple, but we choose not to look at things this way. On the contrary, we study neurosis with the rational mind – and at no point do we either show any interest in studying formal systems, nor in acknowledging that the thinking mind is itself a formal system. We assume the rational mind to be a kind of ‘gold standard’ – the one thing we never need to question. For this reason, the limitations and paradoxes inherent in our thinking are positively guaranteed to stay very deeply buried – which means that any conclusions we come up with as a result of our so-called ‘investigations’ are bound to be complete and utter red-herrings.

Formal systems are simulations and the one important thing to understand about simulations is that a simulation can simulate anything apart from freedom!

We can show straightaway and with no further ado why this has to be the case – why it is that freedom can never meaningfully simulate freedom. ‘Freedom’ simply means that the system does something that we don’t tell it to do – it means that the system doesn’t obey instructions. Or we could say that ‘freedom means that the system is independent of any instructions we might be giving it’. But the whole point of a simulation is that ‘nothing can happen in it unless it has first been told to happen’ – this is wasn’t the case then the simulation wouldn’t be a simulation, it would be the real thing! So this shows straightaway that there is never any freedom in a formal system – freedom is the one thing it cannot come up with…

The absolute lack of freedom in a formal system constitutes a very big problem however! It is not a big problem from the point of view of the system itself – it’s not a problem at all for the formal system since this is how formal systems work, the only way that they can work, in fact. The lack of freedom is not a problem for the formal system but it is a problem for us because the fact that we’re acting out of our rational minds almost all of the time means that we end up living in a world that is entirely made up of mental constructs. We live in the world that the mind creates. We live – on a daily basis – in a formal world that is created for us by our thinking minds and because there is no trace of actual freedom in this world (as there is in the ‘informal’ or ‘uncreated’ world of actual reality) this deficiency creates a very big problem for us, albeit a problem that takes a period of time to fully manifest…

So the snag inherent in all simulations (which is the absolutely absence of any genuine freedom) is the ‘very big problem’ that lies behind all neurotic disturbances. As we’ve said, the absence of freedom isn’t a problem for formal systems (since a formal system can’t exist without it) but it’s no good at all for us because we are not formal systems! That is not our nature – we’re not formal constructs. For consciousness, the lack of freedom is – we might say – something akin to a deadly poison – it can only thrive and be itself when it is given the space to do so, not when it is not told what to do and how to do it, which the situation that the rational mind likes to provide it with. Rationality controls everything because that’s what rationality is, and so when rationality is King, when it is placed above everything else, then a terrible life-denying sterility comes about, for all that there is initially (perhaps) the neat and satisfying illusion of ‘things being well managed’…

To talk about ‘consciousness’ in this way – as if it were an actual primary phenomenon in itself, and not some specialized function of the brain that is going to be, at some point, rationally dissected and understood, tends to sound rather ‘unscientific’ to us. We can talk about magnetic or electric or gravitational fields as if they were primary phenomena, but it doesn’t seem right to us to speak of consciousness like this. We have this idea that our understanding of nature is made up of known units, which can be fitted neatly together to form a complete whole. This is the ever-popular ‘jigsaw paradigm’ in which knowledge is seen as a composite structure to be slowly and painstakingly assembled until one day it is ‘complete’. A piece is not added to the jigsaw until it has been understood completely, with nothing left out, and so when all the pieces finally fit together that will be ‘the answer to everything’. We will all then let out a great cheer! According to the great physicist Richard Feynman, however, this is not how it is – we can define the force of gravity, for example, but in order to do this we have to bring in the speed of light, and in order to define the speed of light we have to bring in yet another piece of the so-called jigsaw, and so what is happening is that all the different pieces of the jigsaw are being defined in terms of each other. This is fine, there’s no problem with that, but these are then relatively true not absolutely true definitions – we can’t come up with any ‘absolutely true definitions’ because we would need to get out of the universe in order to make them! In order to be truly objective in the way we want to be we would have to scrutinize the universe from somewhere outside of the universe.

The popular view of science has always been that it provides us with absolutes, with black and white ‘facts’ about the universe, and this is not unlike a small child thinking that his or her father ‘knows everything’. When we grow up ourselves however we come to realize that he didn’t know everything after all – and that even the president (or whoever it is that we put our trust in) doesn’t know everything. None of our ‘father figures’ know everything and seeing this means of course that we have outgrown the need for reassuring ‘father figures’! Science isn’t a supremely authoritative father figure whose role is to provide us with a wall of absolute definitions, so that we never have to encounter the fundamental irreducible uncertainty of the universe – on the contrary, the thrust of science has been to introduce more and more relativity into the picture, which is baffling for the rational mind and not reassuring at all. There is nothing reassuring about relativity, but there is something very real about it. The world is a far bigger place (an infinitely bigger place) when we lose the false absolutes that we have been brought up on and so when we find the courage to live in this bigger world, this could be said to constitute ‘growing up’ and ‘stepping out of the play-pen’ (to use Joseph Campbell’s apt phrase) which society itself would encourage us to spend our whole lives within. In fact, society – or ‘the collective way of seeing the world’ – is the play-pen we need to outgrow the need for. The social world is a safe, non-relativistic simulation that we don’t ever need to question.

To imagine that consciousness itself ought to be something that can be ‘totally defined and understood’ is part of this same infantile outlook. We want to ‘know what it is’ so that we can be ‘reassured’ by this knowledge; we want to subsume it within our standardized formulaic mechanical description of the world and all the phenomena in it so that it won’t have the power to challenge us any more. We want to put it into the box. What we can’t know is bigger than what we do know (what we know on a routine basis) and so we’re trying – as always – to escape into a smaller and less challenging universe. We’re down-sizing. We’re simplifying the picture.

Instead of trying to define consciousness as a small thing, therefore (i.e. instead of thinking of it as being ‘just one piece of the jigsaw’) we could venture down the other road and say that it is actually ‘the biggest thing going’ – the ‘biggest thing going’ being nothing more than the sense of infinite relativity we get when we realize that we only get to think we ‘know’ anything by playing a game, and refusing at the same time to acknowledge that we are playing a game! So we could say that consciousness is when we see that each part of the jigsaw only has the meaning that it does have in relation to all the other parts of the jigsaw, so that when we take the jigsaw as a whole, there is no ‘meaning’ to it at all. There can’t be any meaning to the whole thing because there’s nothing else to compare it with, and all meanings are derived (or ‘negotiated’) through the act of making comparisons.

Consciousness – in this view of it – is therefore nothing other than ‘the big picture’ where ‘the Big Picture’ equals infinite relativity. Or we could also say that consciousness is when we have the perspective, the ‘freedom of perception’, to see that all our definite statements about the world are only definite because of the limited way in which we choose to look at things. Consciousness equals a loss of ‘positive data’ rather than an addition – we know less as a result of being conscious rather than knowing more! The more we know the less space we have, and the less we know the more space we have. Consciousness, in this scheme of things, equals infinite spaciousness therefore!

This clearly means that consciousness isn’t a ‘thing’ – it means that no matter how we hard we try consciousness can’t be made into a finite mental object that we can turn over in our minds and examine from all angles. This tends not to be a very satisfactory resolution of the problem to us! No Nobel prizes are going to be handed out for anyone who writes a paper coming out with a damp squib such as this. What use is it to say that consciousness equals infinite space, where ‘space’ means ‘the thorough-going absence of all positive knowledge’? How does this help us? It’s more like a slap in the face than anything else.

The fact that this ‘negative way’ of looking at consciousness tends sounds ridiculously unsatisfactory (and not worth getting excited about at all) to us demonstrates rather neatly what we might call the hidden insanity of the categorical mind. We want to turn consciousness into a mental object, like all the rest of our mental objects, so that it no longer has the power to seem mysterious to us. We want to understand consciousness in an objective rather than a subjective way, and the way we intend to do this is by making it the object of our categorical knowledge (since it is only through our mental categories that we can know anything).

So another way of putting this is to say that we want everything to be a mental category – we want everything to be a defined class within the filing system of the rational mind. We can’t after all take something seriously unless it does match one of our categories, unless it does belong in a defined ‘class’ – nothing can be real unless it can be defined. The situation where everything is a set, where everything is a category, where there isn’t anything that isn’t a fully paid-up member of a set or category, is however utterly absurd. To want to do this to the world is a profoundly insane sort of a thing – it is evidence of pure, unmitigated, no-holds-barred madness. Essentially, what we’re trying to do is to have ‘a smaller picture without a bigger picture’ – i.e. we’re trying to make everything trivial….

If we do have a bunch of sets then it must be true that there is a bigger picture in the sense that there is The Sum of all Possible Sets – we can’t really escape from this. No mathematician would ever be silly enough to argue that we can have this set and that set, and yet at the same time insist that there isn’t such a thing as the ‘Universal Set’, which is the sum of all possible sets. That would be like taking a handful of marbles from a bag of marbles and then denying that there was a bag of marbles in the first place! Or it would be like having one particular theory and denying that there are any other, competing theories. Obviously because we do have a bunch of sets there must be such a thing as ‘the sum of all these sets’ but what we want to say (for the sake of neatness!) is that the sum of all these sets is also a set – i.e. we want to say that everything that exists is capable of being exhaustively defined just as the contents of any individual set can be defined. But then if ‘everything is defined’ then what this means is that the sum of all possible sets must itself be a set – a set which must necessarily be ‘a member of itself’ since the sum of all sets includes (of course!) every set that there is, every set that’s going…

Now as soon as we say this we’re in a jam. If we say that ‘the Set of Everything’ must also be a member of itself then this straightaway embroils us in Russell’s Paradox, which is a mathematically elegant way of showing that what we’re trying to do is just plain stupid. A container cannot contain itself – it has to exist within something that is more spacious than itself, something that is not itself! So when we describe the world to ourselves (i.e. when we put it all into boxes) there must always be a portion of the world (an indeterminately larger portion of the world) that is outside of the box, a portion that is more spacious than the box. Or to put this another way, the world is always larger than we describe it as being. And yet we don’t want this to be the case! It’s not at all satisfactory for us. It’s not good book-keeping. We don’t want there to be anything that escapes our definitions – we want it all under lock and key. The perverse and self-denying urge to disallow the universe from being any larger than our descriptions (the urge to make sure that it is equal to our descriptions) is therefore what we have called the ‘insanity of the categorical mind’. We’re fighting against spaciousness (that portion of the world which is always one step beyond ourselves) and yet this unpackaged spaciousness is who or what we really are.

A universe in which everything is defined runs slap-bang into Russell’s Paradox because in order to make definitions in the first place there has to be something outside of the definition-making process, something outside of ‘what has been defined’. We can make up as many categories as we wish but in order to be do this we need to be coming from a place of freedom, a place which is itself not a defined category. If I choose I first have to be free to choose, otherwise the choice is not a choice. And if I am free to choose then I am also free not to choose, which means that I am already in a place that is ‘bigger’ than any choices that I might possibly make! Or we could say that before I define anything I first have to be free to define it, which means that I must already be in a place where I don’t have to define anything, a place which isn’t defined and which has nothing whatsoever to do with any sort of definitions…

The ‘negative view’ of consciousness would be therefore that it is that portion of the universe that is bigger than our descriptions, and which is therefore beyond our descriptions. Or we could say that it is that place that we’re in before we say anything – that place which comes before all concepts and which is itself not a concept. So the negative view of consciousness is that it is the inexhaustible source of all freedom – the inexhaustible source of freedom which we unthinkingly utilize in order to do anything. It is the freedom which we use to facilitate all of our mechanical cognitive activities, and which we try to ‘get to the bottom of’ by using these very same mechanical activities. We describe stuff, define stuff, categorize stuff etc by ‘taking freedom away from the situation’ and so – because we get so carried away with this technique – we try to apply it to everything and try to understand consciousness (which is as we have said the freedom underlying all mechanical operations) in exactly the same way…

This is the point we started off by making. We were saying that the state of total objectivity (which is possible only within a formal simulation) really equals nothing other than the complete lack of freedom. The freedom has been drained right out of the situation. The phenomenon that we are being objective about (so that we know ‘for sure’ what it is) has become definitely known to us only because we have surgically removed all traces of freedom from the situation- once we do this then the thing is what we have defined it as being and nothing else, and this is how it gets to be ‘a thing’, this is how it gets to be a regular old ‘positively defined mental object’.

This process is so commonplace, so very familiar to us, that we take it totally for granted. We don’t see anything strange in it. We assume that this is how things are in reality – we assume that reality itself is a domain which has had all the freedom stripped out of it. We assume that things just ‘are’ whatever it is that we think they are, and that this is all there is to it!

The real world is always essentially undefined by virtue of the fact that it actually is real, and not merely a simulation – which is to say, it is not merely a ‘formal description’ of reality as opposed to the actual thing itself. However, having said this we also need to acknowledge that the state of ‘physicality’ or ‘materiality’ only comes about in the first place because of the way in which a huge amount of freedom has been drained out of the system. This collapse of freedom (or we could say information) is what makes the physical physical, or the material material – an infinite number of possible ‘levels of description’ are collapsed into just the one level of description, an infinite number of ‘degrees of freedom’ are collapsed into a meagre few degrees of freedom. Original Symmetry is broken and this is how the tangible, measurable universe gets to come into existence. Materiality congeals out of immateriality, like a precipitate in a laboratory beaker!

So the reason that the tool of the rational-conceptual mind works as well as it does is because it takes the freedom out of the picture in a way that is strictly analogous to the way that the original symmetry break, the original ‘information collapse’, did. There is a difference between the models and maps created by the rational-conceptual mind and the physical domain that it is describing however and that is that our mental models can only ever be accurate in an approximate kind of a way. The mirroring is not exact. Even though the correspondence between model and the measurable details in the physical universe can sometimes be astonishingly close it isn’t accurate across the board for the simple reason that the real world system which we are modelling still has freedom in it somewhere (possible just under the surface) whilst our models – necessarily – have none. As we have already said the fact that the real world has ‘freedom’ in it (i.e. freedom from all possible formal descriptions or specifications) is precisely what makes it real and not a simulation!

Mathematically speaking, we could say that ‘freedom equals randomness’. This tends to sound too ridiculously easy a definition to actually mean anything but when we consider that ‘random’ simply means that it did not come about by design – that it was not produced in some way by a rule-based formula – then we can see that this is really a very powerful way of looking at things. Just as, in maths, we can say that there are two only types of numbers, the ‘random’ and the ‘non-random’ type, we can also say, by way of an equivalent philosophical statement, that there are only two realms of being – the intentional realm, and the non-intentional realm. On the one hand there is the made world, the stated world, and on the other hand there is the unmade world, the unstated world. This dichotomy corresponds to Immanuel Kant’s distinction between the phenomenal versus the noumenal worlds. The former is our understanding, the latter what we are trying to understand.

The ‘made’ world is the world that comes into existence because of precedence, because of design, because of intention. “In the beginning was the word…”, as it says in John 1:1. The ‘unmade’ world, on the other hand, has no precedent – it does not come about as a result of any causes, any design, any intention. The unmade world exists at ‘right angles’ to any intention or design we might possible conceive of – it cannot be ‘prefigured’ by any intention or thought that we might have, and this is just a way of saying that when we come across the unmade world (which we can’t do by design!) this will always come as a radical surprise to us. It is because the unmade world is a radical surprise (rather than a confirmation of what we already expect) that we can say that it is ‘real’ rather than being a mere simulation…

Understanding this dichotomy of ‘the made versus the unmade realms’ does not come easily to us for the simple reason that the only world we know of (and believe in) is the made one. Because the only world we know of is the made one we are automatically subject to what we might call ‘the apparent diversity of the created world’. Because our attention is restricted to the defined realm, which is the realm of formal descriptions, we are deprived of the perspective that we would need to see that the formal descriptions which are provided for us by the rational-conceptual mind are not the same things as what is being described. This means that (through lack of perspective which is caused by adhering slavishly to a rational point of view) we immediately become enslaved by the ‘artificial diversity’ of our own proliferating categories – we become the helpless and confused victims of our own mental constructs!

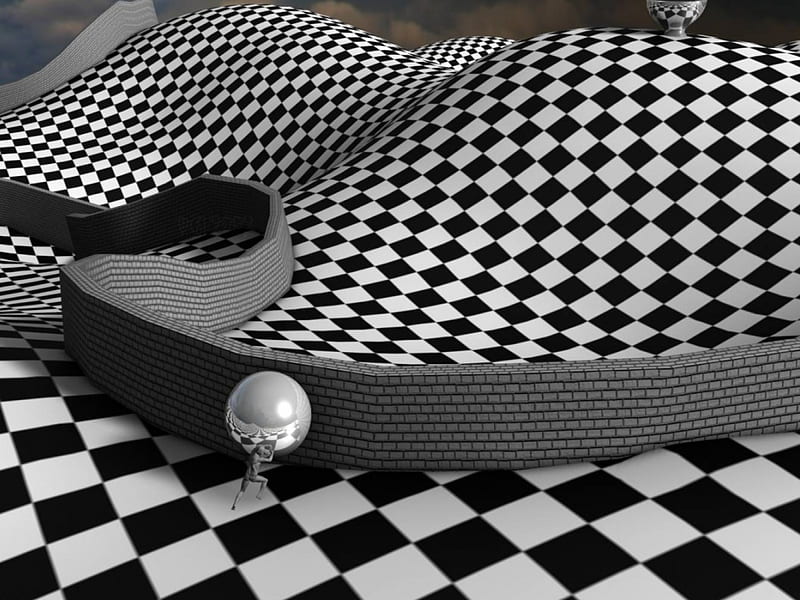

If we do get some perspective, however, then straightaway we can see that everything in the made world is just ‘cause-and-effect’. It’s like a game of billiards. It’s like a row of dominos toppling over… We plainly see that its all just stuff that comes about as a result of law of cause and effect, intention and result, precedence and consequence, and that this is all we need to know about it. There is no mystery in the realm of cause-and-effect, any more than there is any possibility of radical surprise in a simulation and this lack of mystery, this lack of radical unexpectedness, is a clear and unmistakeable demonstration of its inherent underlying ‘redundancy’ or ‘hollowness’. As a handy rule of thumb – if it doesn’t surprise then it isn’t real, and the causal world simply isn’t capable of surprising us!

Without perspective, we over-estimate the causal world, we make too much of it. If we had any awareness of the non-causal world – just enough to know that it was there – then we wouldn’t find the world of cause-and-effect so fascinating at all. It is like being fascinated by a pendulum going back and forth, back and forth, back and forth, in its strictly mechanical way, and because our attention is so caught up in this repetitive motion not seeing the astonishing stillness that underlies everything. If we could see the stillness we would see that the mechanical to-and-fro movement isn’t really worth giving all our attention to! We would see that mechanical activity isn’t ‘where it’s at’ at all. With perspective we can see that the causal realm is entirely trivial – it is not any good for doing anything other than what it is already doing, it isn’t any good for doing anything other than ‘continually going back and forth’. Mechanical cause-and-effect means that ‘nothing comes out of it that wasn’t already in it’ – causality is ‘non-creative’ and since there was never really anything in it in the first place (since there is no freedom in it) this makes the whole business distinctly deficient of anything of genuine interest!

As we have said however, we don’t tend to see this about the causal world. It doesn’t seem sterile to us because we read so much into it – we read everything into it! We ‘read everything into it’ because it’s all we’ve got, because it’s all we’re capable of understanding with out mechanical minds. For the most part it is true to say that we know nothing of the non-causal world – the very mention of it fails to make any sense. How can there be such a thing as ‘an unmade world’, a world that doesn’t have to be created? How can there be a world that has nothing to do with our minds, a world that has nothing whatsoever to do with logic? The consequence of not having any awareness of the non-causal world is that, either implicitly or explicitly, we believe the universe to be like a computer programme. We believe, in other words, that there must be ‘an algorithm for everything’, if only we could find it. We assume that all processes must conform to a pattern. We assume that we should be able to second-geuss reality, if only we could be clever enough. The ultimate example of this sort of thing would be the ‘algorithm for everything’, the AFE (or as it is more commonly known, the TOE). What we don’t seem to want to see is that only trivial stuff can be worked out with algorithms, which is to say, if it can be predicted then it can’t be that interesting anyway!

But as we have said, it’s not just the case that if there is no randomness, if there is no genuinely new stuff happening then everything gets boring and dull. That isn’t it at all. The point is that if there wasn’t any randomness or newness then nothing could ever happen anyway. Without ‘the freedom of the new’ nothing ever happens. The idea of imprisoning consciousness in a world in which there is no freedom to change, in which everything is just a repetition of the old, is a pure horror story – for all that this is what we are constantly aiming for, whether we know it or not! This goal isn’t actually possible – and even if it were possible it would be a total disaster. It would be a nightmare from which no one could ever wake up!

Control means ‘making sure that there is no freedom for anything truly new to happen’, and to the extent that we are invested in control (i.e. to the extent that we are invested in the rational mind) this is what we are sold on, this is what we are putting our money on. Because of our back-to-front way of seeing things, we think that everything will turn out marvellously just as so long as we can make sure nothing radically new (or radically different) ever happens…

For consciousness to exist in a world in which there is zero freedom (i.e. a conditioned world) is for it to be trapped in a terminal situation, although our awareness of the fact that it is a terminal situation may be indefinitely delayed, indefinitely postponed. This is the ‘neurotic struggle’. When our neurotic strategies are successful (which is to say, when we don’t know that our neurotic activities are neurotic and instead believe them to be quite legitimate) then this means we are able to effectively delay this unwelcome awareness. We don’t have to face up to it just yet, we are indefinitely postponing that moment, and we don’t have to face up to the fact that we are indefinitely postponing. ‘Successful neurosis’ means therefore that we are successfully living on the never never! Unsuccessful neurosis, on the other hand, means that awareness of the fact we aren’t getting anywhere living in a world that is devoid of freedom (and that we can’t ever get anywhere) starts somehow to get through our defences, one way or another. Leaks start springing up between the planks of the life boat, and we just can’t manage to bail out the water fast enough to stay afloat. Cracks start unaccountably to appear – the mechanism no longer works as smoothly as it once did, and this means that we actually begin to gain awareness that there is a mechanism there, which is of course something that we had never up to this point suspected…

There are two basic ways in which we can think of how the ‘mechanism of unconsciousness’ can start to fail, to become ‘less than perfect’ in its operation. In both of these cases there is an increase in awareness of the redundancy or hollowness of the whole endeavour, and this awareness – naturally enough – gets to be treated as a deadly enemy, something to be fought against at any cost. The first manifestation of the failure of the system corresponds – we might say -to anxiety. In anxiety our perceived self-efficacy slowly crumbles, and eventually takes a complete nose-dive. ‘Perceived self-efficacy’ is generally considered by psychologists to be a necessary ingredient for good mental health – it means that we perceive ourselves to be the effective authors and executors of our own goal-orientated actions. This is – as we have said – generally considered to be a great thing: we feel confident in ourselves, we feel that we are securely in control, we feel effective, and so on and so forth. Failure of this conditioned perception manifests on the one hand in me not being able to make clean decisions about what I want to do, and on the other hand in my chronic irresolvable doubting of myself with regard to my ability to obtain the goal even when I do decide upon it! This is anxiety in a nutshell.

We are culturally extremely indisposed to entertaining such a view of anxiety, for the simple reason that we are invested in the idea that there really is such a thing ‘an effective causal agent’ and that we are it! Equally, we could say that we are invested in not seeing that the universe is a spontaneous sort of a thing, and that we too are essentially spontaneous. Being ‘essentially spontaneous’ means that there is no actual isolate entity or agent which is the author of its own decisions – spontaneity means that we simply can’t pin down such an entity, such an agent. Things happen but no one really makes them happen, despite the compelling illusion that we generally have to the contrary. What is more, there is nothing so very dreadful about this – it actually feels good to be spontaneous. There is tremendous freedom in it, tremendous creativity in it, tremendous zest in it! Who would want to be not spontaneous?

When we see ourselves as the sealed and self-contained ‘causal agents’, however, and we do our best to stay in the driving seat (or stay in control), then we are never too far off from the essential ‘glitch of neurosis’ – a glitch that can be simply explained by saying that the more we try to free ourselves from the pain of restriction, the more painfully restricted we become. As long as we hang on the notion of the defined and therefore isolated self (which is constantly trying to define its own environment, as well as constantly trying to define its own behavioural and mental output) we are hanging onto a world of conflict, a world of invisible self-contradiction. To be a fully-defined causal agent who is fully in control of his or her own actions (who defines his or her own actions) is to be embroiled in paradox, as we have said. This situation sounds secure to us – but in reality it’s an absolute, unmitigated, non-terminating nightmare!

The other basic way in which the system fails, and we start as a result to become aware of the hidden redundancy or what we’re caught up in, is where the brightly-coloured ‘lures’ of the rational-conceptual mind, which have the function of tempting us ever-onwards in our goal-orientated activity (even though ‘onwards’ really means going around in tight circles) start to lose their apparently infallible attractiveness. Our goals start to reveal themselves as being drab, as being shabby, as being ‘not worth the paper they are printed upon’, so to speak. The mental projections which normally seem to promise so much lose their magnetic pull and as a result we are just not motivated by them to carry on. The game no longer commands our attention. The charade is revealed as a charade. So we lose interest in all the things we normally would be interested in, and it seems as if life itself has lost its interest to us. This ‘demotivated and disillusioned state of affairs’ corresponds – we could say – to what we generally call clinical depression.

When I am depressed the goals that normally lead me on no longer interest me – I see nothing in them, and in fact the very idea of pursuing them seems abhorrent. The goals and pastimes that I usually find so motivating now seem to mock me, if anything. There is more to depression than just ‘lack of interest’ of course – there is the ‘affective component’ and there is the complete lack of any feeling of self-worth, which turns into ‘negative self-worth’. The point about all my goals is that they are really nothing more than projections of myself, and so the perception of the utter redundancy of all these mental projections is really a displaced perception of my own complete and irredeemable redundancy. It is not the case in depression that life itself no longer interests me – even though this is what it very much looks like – but that my own sterile mental representations of life no longer interest me. And why should they interest me, seeing that they are irredeemably sterile, in the same way that everything about the mental simulation of reality within the weary confines of which I live out my life is irredeemably sterile?

The only reason that the lures dangled in front of my nose by the rational simulation don’t usually look sterile to me is because the ‘mechanism of unconsciousness’ continues to work flawlessly. If we say that ‘the mechanism’ works by separating positive from negative, so that the advantage we are going to obtain as a result of seizing the prize (or ‘going for the bait’) seems to have been effectively separated from the equal-and-opposite disadvantage that we incur from seizing the prize, going for the bait, then we can say that the failure of the mechanism is when we start to see that there is actually is no separation. Advantage and disadvantage are inseparable, which means that the advantage is no advantage! When we see the plus and the minus, the advantage and the disadvantage together in this way then what we are seeing is pure explicit ‘redundancy’…

If we could see the redundancy of the system very clearly then naturally we simply wouldn’t engage in it, but this is not the same thing as ‘depression’. On the contrary, this is actually the spiritual virtue of ‘non-attachment’ – which is when we don’t take the hollow enticements of samsara seriously any more, because we can plainly see that they are hollow! Seeing that the system of mental representations is redundant is one thing, but gaining this insight after we have invested a life-time in service to that system is quite another. If I spend a life-time believing in these attractive and repellent projections (as well as believing in the self which is attracted to and repelled by them) and I suddenly get the rug snatched away from under my very feet then the degree to which I have unreflectively believed in all of this is clearly going to be directly proportional to the degree of absolute utter unbelievable shock that I am going to experience when this happens to me…

There is no way that this can’t be the case. The more attachment I have built up over the course of my life, then more painful it is going to be when I have to let go of the illusory set-up that I have become attached to. This is a straightforward case of ‘building a castle on a cloud’ – I have been busily investing in a dream, assuming for the sake of convenience as I do so that the dream is not a dream, and in doing this I am indisputably the architect of my own suffering! Very clearly, the more effort I have put into ‘acting as if the dream were not a dream’, and making this flimsy assumption the basis for everything I care about, everything I think worthwhile, everything that matters to me, etc, the greater the suffering will be for me when that assumption is revealed as being false.

Another way to look at this is in terms of ‘service in error’, as Philip K Dick puts it. Our mistake is in serving a false master so that our very faithfulness gets to be turned against us. The more energy and determination I put into serving the false master, the more it will rebound on me!

The more slavishly we conform to the system of rational thought, the more we embody the paradoxes that are inherent in it. The more we adapt ourselves to the logical continuum, the more we will suffer from the redundancy that is in that continuum, which is something we simply don’t have the perspective to see when we are adapted to it. Just because we don’t have the perspective to see the redundancy doesn’t mean that we won’t suffer from it however – it just means that we get caught up in fighting a long drawn out ‘delaying-action’ until the time finally comes when we no longer have any choice about seeing what it is that we are fighting against seeing! This is the neurotic struggle in a nutshell – we fight as hard as we can against seeing the redundancy until we reach that point of ‘no choice’, that point where we find ourselves unable to stay in control any longer, and then at that point of course we finally do see it – but only with extreme unwillingness, only because we have no more choice in the matter…

The neurotic struggle can therefore be seen as an experiment in fighting against consciousness – we do our utmost to pretend that the causal world is the only world there is, despite all the suffering that this brings us. We deny the reality of the non-causal realm to the bitter end – even though the non-causal world is the only place that true freedom can ever be found…

Image – pxfuel.com