Honesty is something that goes far beyond mere conventional morality – what genuine honesty actually entails is a revolutionary shift in how we understand reality and so when we talk about being honest (in the way that we generally do) we’re talking about something very different – we’re talking about ‘being honest within the terms of the game that we have agreed to play without realizing that we have’. This is qualified honesty. Honesty itself – the unqualified version – takes us beyond all games and because our usual situation is that ‘we are playing a game that we don’t see to be a game’ this is a quality we very rarely – if ever – come across. Until we see that we are playing a game, we can never be honest.

Ram Dass makes the point that when we realise that we no longer have anywhere to hide then at this point we discover that we’re actually free. This is something we don’t see coming – just when we think that all is lost there comes a tremendous liberation. We’re ‘liberated’ because we no longer have to hide, because we no longer have to ‘try to do something that can’t be done’ (which is stressful and very time-consuming). We could rephrase this to say that when we clearly realise that we can no longer lie (when we no longer have the means of lying) then at this point we are free. For the one who is driven by the terrible need to hide, the situation where there is no longer any possibility of doing so is horrifying – what could be worse than this? When we realise that there’s ‘nowhere left to hide’ then this is the worst outcome we could ever imagine – this is panic pure and simple. If we wish to speak in terms of lying then we can say that when we are driven by the awful need to keep on lying the prospect of ‘no longer be able to get away with it’ is ultimately terrifying. It is because the thought of not being able to lie is so terrifying that we can’t ever stop and this is what ontological fear is all about.

All of this, however, is simply how things seem from ‘the point of view of the one who needs to hide’, or ‘the point of view of the one who needs to continue camouflaging themselves with lies’. This is – furthermore – a point of view that ought to be very familiar, very relatable to us. The POV we’re talking about is the POV of the conditioned self, after all. Within the terms of the conditioned world within which we live we have the choice of either being honest or dishonest (or so it seems), but on the deeper level there is no choice – we can’t help lying. As P.D. Ouspensky says in In Search Of The Miraculous –

And yet they lie all the time, both when they wish to lie and when they wish to speak the truth. They lie all the time, both to themselves and to others.

We lie all the time, whether we want to or not, and this uncompromising fact takes away whatever dignity we feel ourselves to possess. For the conditioned self, lying is all there is – were the self – for whatever reason – to stop lying then it would simply cease to exist. It would break the conditions of its own existence. The self is its own lie, so to speak. For the concrete sense that we have of ourselves, hiding is something that we absolutely have to do – we need to hide behind the image that we have of who we are, or the concept we have of who we are, and – the ‘lie’ in question is simply that ‘I am this image’ (or that ‘I am this concept of myself’) when this is not at all the case and never could be.

Lying (or hiding), for the self, is the key thing that it needs to do in order it might on carry on being itself (or – rather – that it might continue to appear to be ‘who we actually are’). The conditioned self’s motivation to perpetuate itself is the very same thing as its ‘need to hide’ (in the way that we have just described). We don’t see this as hiding therefore, but as the manifestation of our natural and perfectly healthy instinct of self-preservation. From this conditioned POV this is fair enough – there is no way that it wouldn’t see things this way, of course. To not hide behind the image (or to not claim to be this image or concept) would be ‘suicide’ for the concrete sense of who we are – that would be the end of the road. There is, in other words, absolutely no logical incentive for us to experiment with the painful process of disidentification, the process of letting go of who we think we are (or what we thought life is all about). There’s no incentive to experiment with going down this road at all.

Certainly, there isn’t any sort of cultural support for the process of disidentification – our culture doesn’t see any value at all in states of mind that aren’t connected to ‘a concrete sense of self’! For us, good mental health is all about: [1] having a strong ego (i.e., having a strong sense of personal agency), and [2] adaptation (which is to say, agreeing with the way everyone around us sees things). This conventional formulation of MH makes perfect sense to us, of course, but at the same time there’s no honesty in it. If we were to go down the road of honesty (rather than going down the well-travelled road of merely being ‘agreeable’) then we would see two things about this pretty standard definition of mental health – we would see [1] that there is actually no ego there (either strong or otherwise), and [2] we’d see that when two more people agree on something then the one thing that we can say for sure is that what is being agreed upon is the purest fiction! Even if I (ignoring everyone else) were to agree only with myself about what’s going on, that too would be guaranteed fiction. All agreements are fictional; all agreements are ‘for convenience only’. We can only agree on ‘fixed things’ after all and there are no fixed things.

The only thing that isn’t fictional – the only thing that is guaranteed not to be there ‘merely for the sake of convenience’ – is when there is no agreement, when no last word has been said on the subject. We haven’t put a lid on things and that’s very inconvenient, that never stops being inconvenient. When there is no ‘agreement about how to see the world then we find that we have to give up convenience entirely. ‘The Son of Man has no place to lay his head’, we read in Matthew 8:20. The reason the son of man has no place to lay his head is because there is no consensus and when there is no consensus then there is nothing to hide behind. The Generic World is always opaque – it is always opaque because it doesn’t admit to the possibility that there is anything else other than ‘the regular and the predictable’, that there is anything else other than the flat, unremarkable world of our concepts. It’s opaque because it never leads beyond itself and ‘itself’ isn’t really there. The flaw in this scheme is therefore that there isn’t any such thing as ‘the generic’ – the Generic World is at all times 100% redundant, after all.

To be autonomous is to come out from that hiding place, is to break with the collective web of lies that we are sheltering within. If we can’t come up with an idea that explains ‘what’s going on’ then we can’t hide behind that idea – we have to come out into the open. If we haven’t agreed upon a description of the world then we can’t buy in to the pernicious lie which says that ‘the description is the thing’. Whenever we say that ‘the image is thing’ (or that ‘the construct / concept is a thing’) we are worshipping a false idol, and we are always worshipping false idols. Honesty in this situation means ‘not going along with what is convenient,’ and what we find in this honesty is that there is no personal or private self. That’s just our way of hiding from the truth, that’s just our camouflage; that’s just our mask and when we stop hanging onto this ‘mask’ we discover that there was no ego-entity that was wearing it. That was only ever an ‘inference’ – there is an act but no ‘actor’, a show but no one performing the show. The game we are playing in everyday life however is the game that the personal or private self absolutely is who we are and that it isn’t an ‘empty show’ at all. The personal or private self is very much ‘what it’s all about’, we say, and we couldn’t give a damn about anything else. Because our way of seeing things is to say that there is no deeper reality that exists (in some mysterious way) beyond the everyday self and its tedious activities we are bound to cling to it for all we’re worth, even though this project of ‘saying that we are the self when we aren’t’ is inevitably going to end badly for us (it’s inevitably going to end badly since there isn’t actually anything there to cling to).

Seeing things this way – however convenient the viewpoint might initially seem – sets us up for a life of ‘long drawn-out futile struggling’ therefore. It sets us up for what Joseph Campbell calls ‘the negative adventure’. No matter how we try to spin it this deal is always going to turn bad on us. We cling to the unreal husk (or shell) even though it brings nothing but suffering and we deny our ‘core being’, even though this is the source of all well-being and so of course this isn’t going to work out well for us! It’s simply not true that behind the ‘shop window dummy’ of the agreed-upon ego there is nothing – what lies behind the crude (and endlessly repetitive) performance of the shop-window dummy is everything.

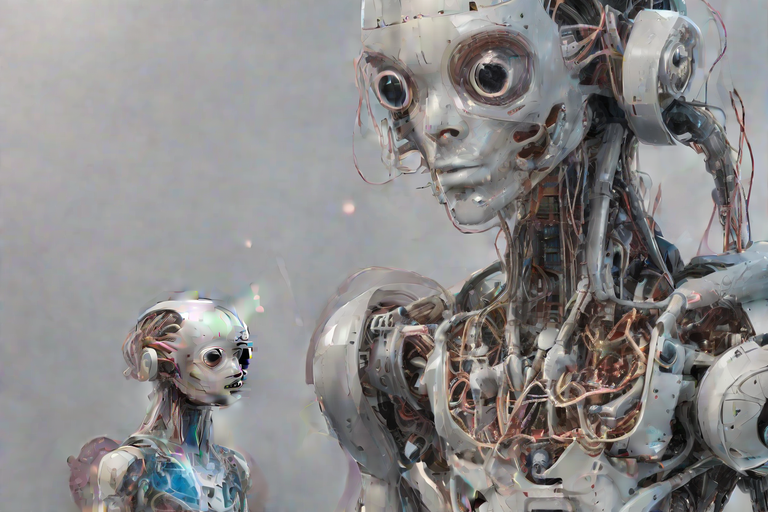

Image – wallpapercave.com